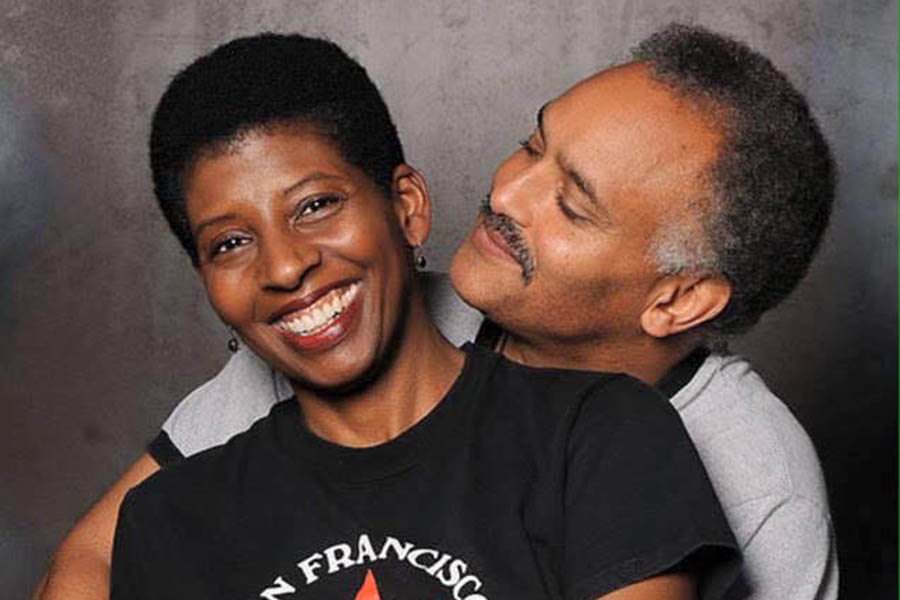

In their third-floor, one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco’s Western Addition, theatre artists Velina Brown and Michael Gene Sullivan are sitting on a couch beneath a big window. The window looks out on a drought-stricken backyard, where Sullivan sometimes goes to write. (He also likes to walk the city streets endlessly while thinking about his scripts, as Dickens did.) Brown, who’s tall, with glowing skin, wears dangling earrings and a fuchsia top. Her long legs are folded beneath her. Sullivan sports a small mustache. They’re “youthfully middle-aged,” they declare. Their 13-year-old son, Zachary, is home from school today with a sore throat, silent behind a curtain in his tiny sleeping loft in an adjoining room.

It’s fall, and the busy couple is taking time out to discuss their marriage, the vagaries of parenthood, and their lifelong commitment to leftist politics and theatre, which they see as inseparable. Freedomland, the play that Sullivan wrote two years ago for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, about a young, black Afghanistan veteran returning home to another type of war, is on tour with the Tony-winning political/satirical collective of which Brown and Sullivan are longtime members. Sullivan has been the Mime Troupe’s resident playwright since 2000. His adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984, which played late last year in Queens, opened a decade ago directed by Tim Robbins with the Actors’ Gang, who then toured the show around the country and the world. The adaptation has since been published in the U.S., Canada, and Spain, with productions on with performances and productions on five continents. The Russian translation, Sullivan proudly notes, is scheduled to be this season in Kiev. For her part, Brown recently returned from New York, where she sang and recorded songs of the Spanish Civil War for a Lincoln Brigade veterans organization, an ongoing project for her. And she just finished teaching one of her “The Business of Show Business” seminars.

This month both will be organizing a fundraiser for the Mime Troupe. Brown will also be preparing for a three-week tour to France; she’s in the cast of All Aunt Hagar’s Children, a verbatim staging, by the San Francisco literary theatre company Word for Word, of the Edward P. Jones short story. Sullivan, fresh from the holiday show She Loves Me at San Francisco Playhouse, will appear in the world premiere of Leaving the Blues, Jewelle Gomez’s play about the singer Alberta Hunter, at New Conservatory, April 3-March 2.

The couple first met in junior high, in San Francisco, in band class. She was an army brat who fell in love with theatre when she saw her father appear in an on-post theatre production of Guys and Dolls the year before he went to Vietnam. Sullivan’s family relocated from Los Angeles when he was 7. His mother, a “Kennedy girl” who participated in Bobby Kennedy’s campaign in California, was in the Ambassador Hotel Ballroom when he was assassinated in the kitchen, so the FBI put the family in a witness protection program. The parents, both radicals, chose San Francisco; they figured that’s where the revolution would start.

Brown played the French horn, Sullivan percussion. “Michael at that time was extremely shy,” Brown says. That’s hard to believe, given that Sullivan now comes off as an irrepressibly jokey chatterbox—a contrast to Brown’s quieter, more measured, but equally vibrant style. “I’d say hi to him in the hall and he’d go the other way. He was being weird,” she insists.

“I was shy,” concedes Sullivan. “But I knew if I ever started talking, I’d never shut up.” He wrote his first play in elementary school—it was about funding for schools—and he also wrote horror stories “so the kids wouldn’t beat me up.” They went to the same high school as well, still in band class and choir together, and when Brown joined a student theatre company, Sullivan joined too, so he could see her.

In college—he at City College at first, where they both appeared in summer musicals, and she at San Francisco State University on a vocal scholarship—they agreed to go on a “test date.” “We even had a test kiss!” says Sullivan. “We were so intellectual! But we were dating other people, and we didn’t start dating for another year and a half.”

Brown went on to get a master’s degree in counseling; Sullivan, studying history, dropped out, just short of a degree, to do what he really wanted to do: act. They married 12 years after their first date; Sullivan says he proposed at dinner in their favorite restaurant—as it turned out, on the very night she’d decided to break up with him because the relationship wasn’t progressing. He just happened to speak first—which is good, he says, because if he’d spoken second, “it would always have seemed a desperate ploy.” Zachary was born 12 years after that.

The decision to have a kid was a big one. Says Brown, “At a certain point I was waiting for clouds to part, for the sign to become clear.” She utters a celestial musical note (both have beautiful singing voices). She imagined life without children and didn’t like how it felt. At about that time, Sullivan—who’d been worrying about having kids in a world of climate change, war and other disasters—came to the same conclusion. They sat down with a calendar to decide when, amid their theatrical commitments, they could schedule a baby. It has helped that the Mime Troupe is family-friendly; babysitting is built into the contracts when the group tours.

“We’ve been extraordinarily fortunate,” says Sullivan. And Brown’s mother lives in the area, so she helped out, and one of Sullivan’s sisters owns a daycare center that Zachary attended. The parents made sure they were never away from home for an extended period of time simultaneously. Zachary came on tour with them; he was a year old when they were in John Brown’s Body at Denver Center Theatre.

Recently Zachary was cast in a TV pilot with a 12-day shoot; since both parents were in a show at the time, they hired an on-site guardian for him. “Now he has a real understanding of our jobs,” says Sullivan. Brown adds, “We’re not about pushing him.” Zachary has been offered other auditions but is circumspect. He has also been offered theatre roles at Berkeley Repertory Theatre, but “that’s on school nights!” exclaims Sullivan. “His bedtime is 9:30!”

The two have directed each other at various times. She directed his solo show Did Anyone Ever Tell You—You Look Like Huey P. Newton? (he does), but mostly it’s been the speedy, multi-tasking Sullivan who has directed Brown. “Directing Velina is always fun,” he says, “but there was a period when it wasn’t.” He was self-conscious at first, knowing that she’d give him notes afterward, “because she’s all about the communicative skills.” But the opportunity kept coming up, mainly at the Mime Troupe. “Getting to go to work with her and then come home and be with her—bonus!” exults Sullivan. Adds Brown, “If you don’t ever work together, you don’t get to see each other much, and there’s a lot of pressure on Monday to be amazing.”

Sullivan, who has written or cowritten 19 scripts for the Mime Troupe (as well as directed and acted in many of them) sometimes finds himself writing for Brown. In Recipe, a comedy about old radicals that premiered at Berkeley’s CentralWorks, he wrote the role of a young journalist for her. He’s currently writing a key part for her in fugitive/slave/act (other non-Mime Troupe plays include a reimagined A Christmas Carol that premiered at Open Door Theatre in Sheffield, England). “I sometimes think, what would Velina do with this, how would she breathe it?” he says. “Even if someone else does, it’s based on her reading it in the bedroom.”

“In the bedroom?” chortles Brown.

Both have acted with such high-profile Bay Area companies as American Conservatory Theater (where they appeared as a couple for many years in the Carey Perloff/Paul Walsh adaptation of A Christmas Carol), Berkeley Rep, and the Magic Theatre. Brown’s acting career has veered toward new plays, such as Aaron Loeb’s Abraham Lincoln’s Big Gay Dance Party, a San Francisco Playhouse hit that traveled to the New York Fringe Festival a few years ago. Sullivan is most often cast in comic roles; Brown—who also regularly books film, television, commercials, and industrials–encompasses a broad range. Last summer she appeared on the Mime Troupe stage as both a wildly athletic cheerleader and the mom of a teenage son, and she relishes such serious roles as the lonely upper-class woman in Terrence McNally’s Mothers and Sons, a recent role at New Conservatory.

“They’re royalty in the world of Bay Area theatre,” comments Robert Kelley, artistic director TheatreWorks, where both have appeared. “Michael’s ability to play across all different races and cultures is quite spectacular.”

Sullivan points wryly to the fact that he and Brown rarely get cast as a couple: She’s dark-skinned, he’s lighter. “Within the black theatre community, we’re color-wrong,” he observes. “The guy’s supposed to be chasing a lighter woman. When we’re auditioning for TV shows, Velina will get called back—with a darker guy. I’m called back with a lighter woman. But if you want to cast a real black couple, that’s who we are.

“I want to direct her as Lady M,” he continues. “Because”—he pounces playfully on Brown—“you have a master’s in counseling! Lady Macbeth has to be superhuman to bolster her husband up…and that drives her insane. She is not evil. An evil person wouldn’t be driven crazy by the deeds. I think Velina would be able to bring extra depth to the role.”

For himself, he longs to play Cyrano. “I identify with him! To never be afraid to speak truth to power, to fight passionately, to know what he wants to say, to always know his enemies are his enemies! I’d probably suck at it. It’d probably be too close.” Brown says she’d like to be in a superhero film: “My special power would be to see the perspective of the other person. The way you can influence someone is not by hammering away about why they’re wrong but meeting them at the level of their concern.” Shouts a delighted Sullivan, “She has a master’s in counseling!”

Above all, both are about living as committed leftists: in their work with the Mime Troupe, in the media roles that they turn down, no matter how well-paid (they’ll turn down work that conflicts with deeply held political convictions—as Sullivan says, “If you can sell your ethics, that means you didn’t have them in the first place”), and in their teaching, lecturing and writing. Sullivan contributes to huffingtonpost.com—he once wrote about being stopped in San Francisco for “walking, talking, driving or bicycling while black”—and Brown writes an advice column on sometimes thorny actors’ issues for Theatre Bay Area; in one issue she responded delicately but firmly to the question, “Why is it OK for actors of color to play roles not written as such but not OK for white actors?” Says Bill English, artistic director of San Francisco Playhouse, “They’re incredibly politically astute.”

“As an actor, writer, and director, Michael has such a shorthand in terms of dramatic structure, speaking to an audience—a meticulous sense of craft,” observes Paul Walsh, professor of dramaturgy and dramatic criticism at Yale, who has read early versions of Sullivan’s scripts in development. “Most importantly, he has a commitment to social and economic justice founded on firm political analysis. It underscores everything he does. His plays…provoke audiences to a personal sense of action. I find that extraordinary. He has a great love for not just the theatre but for the community he’s writing for. And for Velina.”

Adds Ellen Callas, the Mime Troupe’s longtime general manager, “Stylistically, Michael has this high-energy, confident, move-ahead energy. Velina has this very steady graciousness—she’s thoughtful, she really listens to you, she’s gorgeous, she has an amazingly strong stage presence…Michael is silly even when he’s being serious. He’s a tour de force that you have to rein in all the time: ‘No, Michael, you can’t write, act, and direct—pick one!’ Clearly they have a great deal of affection and respect for each other, even when they’re disagreeing.”

But when it comes to their politics—and bringing those politics into their art—they are firmly united. “The partnership is essential,” says Sullivan.

“We knew each other before we were artists,” he adds. “We can understand each other. Our foundation of understanding is very deep…because we’ve lived our artistic lives together.”