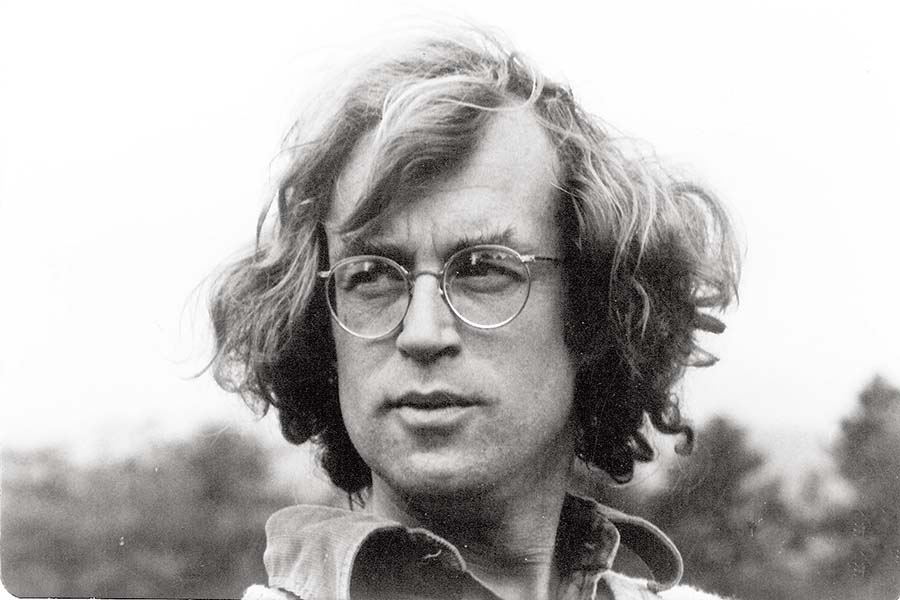

Murray Ross, the founding artistic director of TheatreWorks in Colorado Springs, died in early January at the age of 74.

Murray Ross may be a name you’ve never heard. That’s unfortunate, because he was a genius. He was an artist more committed to and passionate about theatre than most of us could ever dream to be. But for theatre lovers in and around Colorado Springs, he was a household name.

Murray was an artist of the highest regard, an extraordinary academic, and a bold leader in the arts. He loved to stir things up with contemporary work, and he was also truly dedicated to reinvigorating the classics and devising new work. His plays were performed in classrooms, buses, warehouses, basements, and, of course, in more traditional theatres. He put true beauty and goodness out into this world.

He worked with thousands of students, artists, actors, and staff, and he undoubtedly left an impression on everyone he came across. If you were lucky enough to be among those thousands, you know he was wickedly funny and tremendously smart, and a bit of an anarchist, a dreamer, a daydreamer, and a great lover of life. Good wine, great art, dinners around his ancient kitchen table, adventures, storytelling, and spirited debate filled his life.

Murray was the founding artistic director of TheatreWorks, the resident professional theatre company at the University of Colorado—Colorado Springs (UCCS) since 1975. Under his artistic leadership, the fledgling suburban theatre company grew from a small community program that offered three shows a year in a converted classroom, to a robust, professional company that is now about to move into a new $70 million arts center at UCCS. By the numbers, THEATREWORKS has more than1,600 subscribers, produces seven shows a year, has employed thousands of artists, and now serves nearly 30,000 people annually through mainstage programs and educational outreach.

But Murray wasn’t all that interested in numbers—unless of course the budget was threatening to compromise the magic he had planned for his next show. He was interested in great theatre—classics, contemporary plays, difficult work, controversial dramas, side-splitting comedies, and site-specific projects. The company has produced Shakespeare in city parks for decades, and Murray wrote, “Shakespeare outdoors is downright democratic, erasing class boundaries, welcoming everyone equally…Shakespeare shares the park easily with dogs, skaters, fountains, jet planes, coal trains, motorcycles and soft ice cream. It’s all good.”

He produced more than 40 productions of Shakespeare’s plays. Pure magic happened during King Lear when the clouds opened and pummeled the show’s tent during the play’s infamous storm. Murray was in good with Shakespeare, and nature. They made an incredible team.

That was only the beginning. From medieval morality plays to Shakespeare, to devising work inspired by regional history, tall tales and classic texts, Murray took his audiences on adventure after adventure in the Dusty Loo Bon Vivant Theater (the theatre on campus) and out. In a moment of true inspiration, he staged Everyman on a city bus that left its audiences alone in a snowy cemetery as an angel welcomed them to heaven with an aria. It was genius. He took David Ives’s Venus and Fur to a vacant nightclub downtown, and the Mystery Plays to abandoned warehouses.

He would always ask what you thought of the show, and then he genuinely listened. Never defensive and always curious, he constantly asked you to think deeper, to be articulate, and to have an opinion.

Unlike so many of us, Murray was always the same Murray. Whether he was at his kitchen table, at a board meeting, in a classroom, in the rehearsal hall, or lunching with a donor, he was Murray.

It is no surprise that students, artists, and audiences loved him—he was genuine and honest. He was never one to put on airs, but also not known for sugarcoating anything. His notes were epic—in length and poetry. Never has a man had a more robust competency of the English language, and he was prolific. His hundreds of essays, beautiful presentations, and correspondence (both personal and professional) would fill volumes.

In his own words (which appeared as the last line of his directing bios for years), he was married to the painter Elizabeth Ross, was the father of four splendid sons (two acquired, two sired), and was regularly walked by his dog, Toby.

Once more, to quote Murray, “In play we are free and we are human, and in the theatre we are free and human together.” Join us in honoring his legacy, whether you knew him or not, by remembering and celebrating the power and beauty that comes from being human, together, in the theatre.