Playwright, scholar, and dramaturg Leon Katz died recently at the age of 97. He served for many years as a professor at Carnegie Mellon and later at Yale.

Leon Katz taught me what a play is. How it is written, how it works onstage, and how it can be cracked open to reveal the zeitgeist. I was one of thousands of students over 60 years who was mesmerized by his wisdom, charmed by his wit, and challenged by his summons to the ideal. For us he was an inspiring teacher, but he was also playwright and actor, scholar and critic, mentor and muse, father, friend, godfather of American dramaturgy, champion of the avant-garde, and all-around mensch. When he died in January in his home in Encino, Calif., the American theatre lost a bit of its better self.

Leon was a child of New York City. The son of a grocer, he grew up in the Bronx, attended City College of New York, and served in the Army Air Corps during WWII. He received an M.A. (1946) and a Ph.D. (1952) in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University and worked as a film and drama critic on radio and television while launching a lengthy and peripatetic teaching career that included stints at Cornell, Vassar, Columbia, Manhattanville, Cornell, Stanford, and San Francisco State.

From 1968 to 1981, he was an irrepressible figure in the Pittsburgh theatre community, first for nine years at Carnegie Mellon and then at the University of Pittsburgh. As artistic director of the 99¢ Floating Theatre, he was instrumental in bringing the Living Theatre to Pittsburgh to create The Money Tower (part of their Legacy of Cain cycle). Then, from 1981 to 1989, he was co-chair of the Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism program in the Yale School of Drama. At 70, he “retired” to Los Angeles but kept right on teaching at UCLA and later at UNC-Chapel Hill. At the Mark Taper Forum, he was a consulting dramaturg on Angels in America. In 2012, he published Cleaning Augean Stables, his comprehensive analysis of dramatic structure (and a window on his worldview).

Wherever he taught, Leon’s lectures on Western drama and on dramaturgy were the stuff of legend. He seemed to know everything about everything and lectured on subjects from Hrosvitha to melodrama with the same searing intellectual passion. He would enter a classroom of waiting students, sit down at a small table, place a pack of menthol cigarettes to one side and a can of diet soda to the other, and ask, “Where were we?” Given a prompt, he would ponder a moment, as if summoning a genie, then exclaim, “Ahh! Yes, yes!” and launch into a fully formed lecture remarkable for its erudition and enthusiasm. His voice, urgent and soothing all at once, had the ring of truth, as though he was revealing the secrets of the theatrical universe. If he had notes on the table, I don’t recall him using them.

As a playwright, he was more Artaud than Brecht. His was a theatre of extremes, often punctuated with sensational jolts and graphic displays. Many of his plays were adaptations—of commedia scenarios, of novels by Kafka, Joyce, Proust, or the Marquis de Sade, or of classic plays, such as Oedipus and The Dybbuk, ripe for reimagining. In 1970, at the Judson Poets’ Theater, director and longtime friend Lawrence Kornfeld staged Dracula: Sabbat, which rendered Stoker and pieces of The Tibetan Book of the Dead as a ritualistic Black Mass. Two years later at Judson, Katz, Kornfeld, and composer Al Carmines teamed up on an operatic adaptation of Gertrude Stein’s massive modernist novel The Making of Americans, seen again at Baltimore’s Center Stage in 1990. In 1996, for the Phoenix Theatre, Julie Harris played the title role in Sonya, his play about the dying days of Tolstoy in the Imperial Russian town of Astapovo.

As a scholar, he will forever be recognized as one of the foremost authorities on Stein and in particular The Making of Americans, the subject of his dissertation at Columbia. In the process of that research, he discovered Stein’s notebooks from that time and in 1952-53 conducted extensive interviews with Alice B. Toklas about them. He continued to work on those notebooks and his exegesis of Stein’s magnum opus for the rest of his life.

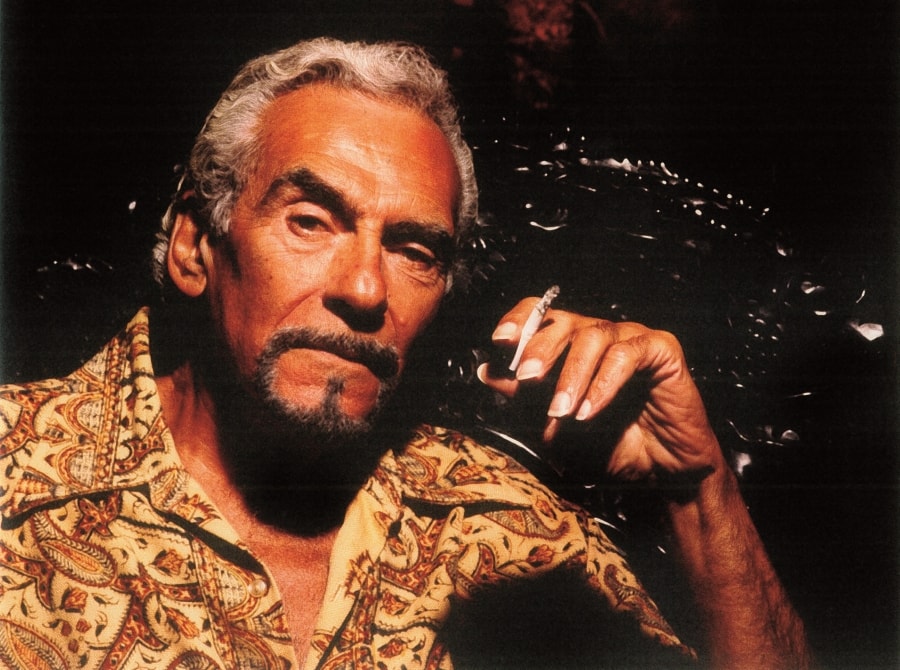

Leon was in his 50s and I was a 22-year-old neophyte playwright when I first studied with him at CMU. He was an imposing presence at first, thanks in part to his dapper dress, tightly trimmed goatee, and the large metal head-of-Medusa ring he wore on his pinkie. In appearance and demeanor, he became my image of Ibsen’s Judge Brack, even after I came to know him as very much the opposite in character. He loved Miami and would fly down there sometimes in the hot summer months to stay in a nice hotel and get some writing done. He couldn’t be bothered to pay a parking ticket. He had a hearty laugh that could shake a room. He liked to watch TV like anybody else.

I followed him to Yale in my 30s, not really knowing what a dramaturg is but knowing that I had a lot more I needed to learn from him if I was to be a teacher myself. More than anyone, he gave me the tools I use to do my job so that now, in my 60s, I feel as if I owe my livelihood to him. He insisted that all his students, regardless of theatre discipline or profession, develop their own “idea of a theatre,” one that reflected their personal vision and values, and then pursue making that idea reality with missionary zeal, despite the threat of compromise and shortcoming.

In his 1970 Newsweek review, Jack Kroll described Dracula: Sabbat as a “work of absolute authenticity—with beauty, dignity, gravity and sensuality, rare to the point of near extinction in any part of our contemporary theatre.” I would say the same of Leon himself. He left an indelible mark on all who knew him. One of many recent online tributes comes from former student Rick Davis, who calls on us, in the words of G.B. Shaw, to “rejoice irrepressibly in [Leon’s] memory.” Or in the cadence of his beloved Gertrude Stein: “Any one could be one not very constantly remembering his being a dead one, his having been a living one. Any one could remember this thing, his having been a dead one, his having been a living one.”

Scott T. Cummings teaches what Leon Katz taught him at Boston College.