On Aug. 10, 2014, Seth Gordon, associate artistic director of the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis, was driving home from Chicago with his wife, a bit baffled by what he was hearing on the radio. “We thought we were listening to the national news on NPR, but the story appeared to be a local one,” Gordon recalled.

The couple had been celebrating their anniversary and hadn’t heard that Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old, had been killed by white police officer Darren Wilson. The shooting in Ferguson, Mo., a suburb of St. Louis, would soon grow from a local story into a global flashpoint, setting off a national discussion and a movement centered on police violence and race.

But it was still also a local story. By the time the Gordons heard the unsettling radio report—news that would change their lives over the coming months—the painful discussion had already begun. In subsequent days, Ferguson became a buzzword, riots broke out, and the Black Lives Matter gained national recognition.

While the streets erupted in protest, theatres sprang into action as well. With surprising immediacy, short plays—10 minutes long, 5 minutes, even 1 minute—arose in reaction to the shooting in theatrical and activist circles around St. Louis and across the country. Gordon felt strongly that the Rep, one of the area’s largest nonprofit theatres—it has a subscription base of 13,000 and a 763-seat mainstage—should respond too.

“We needed to find a considered and thoughtful and evenhanded way to engage in discussion with our audience and with the community about what happened,” Gordon reasoned.

Rep artistic director Steven Woolf agreed. “We thought we needed to address the issue from one of our theatres,” said Woolf (the Rep also houses a 125-seat studio space). The question, Woolf said, was, “How can we fashion something that will be effective? We needed to find a way that made sense for us.”

Should the Rep commission a new work about the Ferguson case as part its Ignite! Festival of New Plays, which supports the creation of three new plays per year? Typically, these plays are simply read in front of an audience. But as the Black Lives Matter grew and incidents of police violence and protests showed no signs of abating, Gordon felt that the topic deserved a full staging. He reached out to a friend, award-winning playwright and performer Dael Orlandersmith, to gauge her interest in making something in response.

“Dael writes from truth in a way that I’ve always admired,” Gordon noted.

Indeed, Orlandersmith deals with tough issues, including race, in her work. Her play Yellowman, a Pulitzer finalist the Rep staged in 2006, is about a fair-skinned black man and a dark-skinned black woman growing up in South Carolina; Orlandersmith unpacked her fraught relationship with her own mother in her solo work Forever.

Gordon suggested that the dramatic response to Ferguson should be a mosaic of voices and perspectives, all played by one person, “so we wouldn’t be so focused on what the people look like.” Orlandersmith liked the idea. She made clear that while she didn’t want to go into the disputed details of the shooting, she wanted to show how individuals from different walks of life responded to what happened. This, she and Gordon hoped, would spark much-needed conversations between people with differing views.

“People are so filled with feelings, they can’t see other people’s reality,” she noted. “My job as a writer, in a nutshell, is to look at different perspectives without judgment.”

That’s the job she undertook when she traveled from her home in New York City in early 2015 to conduct interviews in St. Louis. Ed Reggi, a local actor and community organizer, scheduled several dozen interviews for Orlandersmith’s weeklong visit. Each morning, Orlandersmith, Reggi, and Gordon would load into Reggi’s car and cruise around Greater St. Louis to meet with people in churches, restaurants, homes, and coffee shops. Orlandersmith wanted to focus on both young people and elders, aiming for a sense of past and present.

“Dael was a masterful listener,” reported Reggi. Following a visit to an Urban League meeting full of retirees, she would head to a confab with a group of teen activists. No matter who she was talking to, said Reggi, “She’s totally there, totally present.”

Orlandersmith didn’t record the interviews, and she took few notes—she didn’t want the play to be verbatim reenactments of the conversations she’d had. “I made it very clear to everyone I spoke with that I don’t have a right to invade their lives,” she said. Determined to avoid voyeurism, she created composite figures that drew from multiple interviews, as well as from people the artist had encountered in other parts of her life.

One afternoon, Orlandersmith was sitting in Cathy’s Kitchen, a restaurant in Ferguson, speaking with Marcellus Buckley, known as “the Ferguson poet.” He asked if she wanted to meet Michael Brown’s father and stepmother. Orlandersmith agreed, and after an exchange of texts and a short wait, Michael Brown Sr. and his wife, Calvina, came in to talk. Some of what they told her became the only lines of verbatim text in the resulting play. These searing lines recount what they said when Orlandersmith asked them if they could forgive Officer Wilson for killing their son.

“I can forgive Darren Wilson,” Calvina Brown replied. “I know God has forgiven him. I hope he can forgive himself.”

“I ain’t there yet,” Michael Brown Sr. admitted. “I got work to do.”

Orlandersmith returned to New York to work on the play, discussing it with longtime collaborator Neel Keller, associate artistic director of Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, who happened to be in town to direct Orlandersmith Forever at New York Theatre Workshop. The proximity paid off. It was Keller who first mentioned the Bible verse from which Orlandersmith’s play would take its title, Until the Flood. “It captures the sense of something welling up that could be apocalyptic or cleansing when it recedes,” Keller ventured.

By December 2015, Orlandersmith was ready to read a version of the play to Keller, Gordon, and Woolf in a small studio in NYC. “We all thought it was quite compelling,” said Woolf. “It was a remarkably evenhanded look at a really complicated situation.”

Revisions shortened the play, comprising eight monologues and a poem, to a brisk, 70-minute one-act. It presents a series of characters not directly involved in the shooting. There’s Louisa Hemphill, a black retired school teacher in her early 70s, musing about bygone activist days in New York City. There’s also a retired white police officer speaking about the racial tension inherent in his work, and a white high school teacher who says she lost a friend by expressing sympathy for Darren Wilson. And there’s Dougray Smith, a white electrician who openly relishes the idea of shooting down blacks in Ferguson.

Two black male teens appear: One is angry and fantasizes about committing suicide by cop, while the other dreams of escaping to college in California. There’s also a black barber named Reuben Little. The final character is Edna Lewis, a black Universalist minister, who talks about going to the protests in Ferguson and praying for blacks and whites, police and protesters alike.

So it ends with a preacher. Does that mean that Until the Flood has a redemptive message?

“Everybody says, ‘Oh, we have to give the audience hope,’” Orlandersmith noted. “I say, ‘No, we have to tell them the truth.’ And the truth of it is that Michael Brown is dead. Darren Wilson has to live with what’s happened. And even though he is still physically on the planet, his life will be dominated by this act from now on. How do you live with that?”

In March 2016, after reading the play as part of Ignite!, Orlandersmith began to organize her artistic team. Many had also worked with her on Forever, including set designer Takeshi Kata, lighting designer Mary Louise Geiger, and costumer Kaye Voyce. That June, everyone except Voyce traveled to St. Louis for three days of creative meetings and to get to know the city.

The group headed to Ferguson and the Canfield Green Apartments where Michael Brown had lived. They visited Brown’s grave, then went to Cavalry Cemetery to see where Tennessee Williams and Dred Scott are buried. This got them thinking about memorials.

“We wanted to try and find some way to make the set feel that it was based in St. Louis, but also international,” said Keller. He and Kata decided to create a shrine of stuffed animals, signs, and candles like the one that spontaneously sprang up for Brown—and around tragic sites the world over.

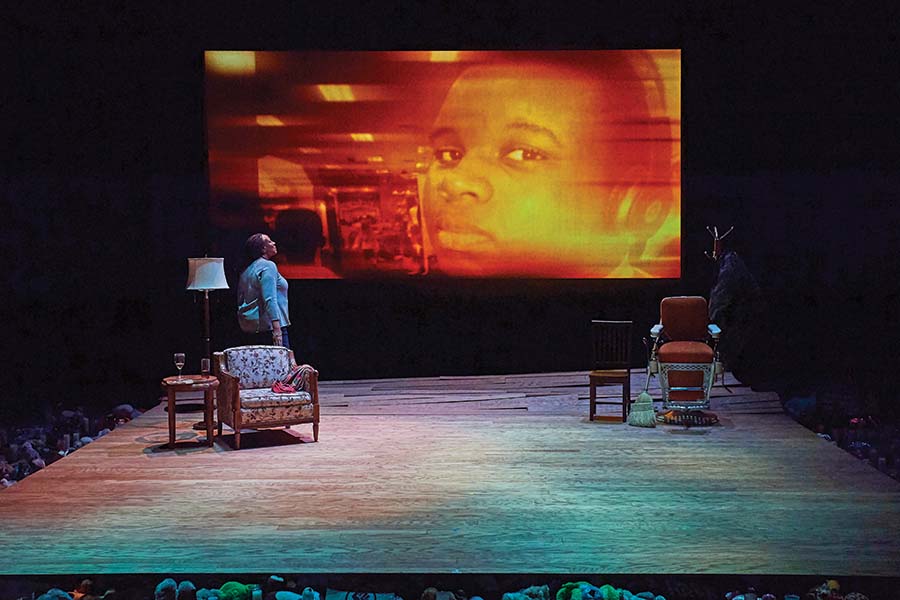

The action of the play would be staged on a single platform with a waviness to the boards upstage—the subtle suggestion of a flood pushing up the floorboards. As more shootings and protests occurred across the U.S., the work “became more and more relevant,” Kata says. “And it felt violent.” So as he worked, he made the part of the platform pushed up by the imaginary water even rougher, as if the wood were buckling under pressure. The area around the platform was furnished with just a chair, lamp, and side table at one end for Louisa Hemphill, a barber chair at the other for Reuben Little, and a wooden chair in the middle for most of the other characters.

Projections designed by Nicholas Hussong, who joined the crew later in the summer, appeared during the transitions between characters. Hussong based his images on people and places around St. Louis, but abstracted them to suggest universality. “Blurring the lines a little bit lets the mind see past the edges, as opposed to seeing ‘Here is exactly where we are,’” Hussong explained.

Mary Louise Geiger, the lighting designer, worked closely with Hussong to balance colors, and sound designer and composer Justin Ellington joined the crew later to create a soundscape for the play.

“I started with St. Louis music history and with the blues and ragtime,” Ellington noted. “But I think the message of the story is so much bigger than St. Louis.” He worked with Orlandersmith—a big music fan, as any of her Facebook friends can attest—to incorporate protest music of the 1960s and ’70s as well as original compositions. “My goal was to not resolve,” Ellington said. “So a lot of the chords I was messing around with were sustaining chords—chords that do not resolve. With the show, I don’t think it’s our goal to have an answer as much as it is to pose a question.”

With the music created, Ellington still had one more piece to contribute. Keller and the Rep had obtained from KWMU, St. Louis’s NPR station, sound clips from reportage about Ferguson. Ellington incorporated the mix of voices into the show’s soundtrack.

While the other designers focused their work on delineating the differences among the eight characters, costume designer Voyce decided to focus on what they had in common. She and Orlandersmith agreed not to do elaborate costume changes, instead testing the idea of using just one telling item for each character. That meant when Orlandersmith walked onstage, she needed a basic costume that would work with all eight characters. It turned out to be what Voyce calls “the American folk costume—what we almost all wear at some time: jeans, a T-shirt, and running shoes. There’s something about those things that feels quintessential 2016 American.”

So Orlandersmith put on a St. Louis Cardinals jacket to play Rusty, the retired white police officer. A shawl wrapped around her shoulders transformed her into Louisa; the same shawl, draped around her neck, made her Edna. Since the play wasn’t connected by an overarching story and none of the characters even mention each other, the production revolved around the conversations initiated by Orlandersmith. Said Keller, “It’s all about those conversations, so our work has been very much about: Who is that character, and why do you think they wanted to share the things they wanted to share? How do they add up? Part of our work has been to highlight or excavate those hidden parts of the characters.”

Until the Flood had its world premiere on Oct.14, 2016, to a crowded but not sold-out house. In the lobby were interactive elements, including an area where people could write what they hoped for the future of St. Louis; another display highlighted the neighborhoods cited in the show and offered facts about them, including their racial makeup, median housing price, and population.

Reviews ranged from positive to glowing. In the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Judith Newmark wrote that “people who have set ideas about what happened in Ferguson in 2014 may not care for Until the Flood. But everybody else may find someone to identify with—and other people to understand—in the short emotional drama.”

Radio station KDHX called the show “pointedly effective.” Tina Farmer noted in her review, “Orlandersmith challenges easy assumptions while making the case for continued conversation. As an actor, she is thoroughly engaging, with a clear purpose and focused action.”

In Ladue News, Mark Bretz wrote that the drama “is a riveting, thought-provoking production. Certainly, Until the Flood will have its detractors, people who say it goes too far or doesn’t go far enough in assigning roles of villains and victims,” Bretz continued. “What Orlandersmith has achieved, though, is bringing a community’s raw emotions from the streets on the stage in thoughtful and reflective fashion.” Joe and Ann Pollack in St. Louis Eats and Drinks conceded that a few of the characters in the play are “apt to make some of us very uncomfortable. That’s rather the point of things like this: We need to hear things that aren’t in our way of thinking.”

The feedback the Rep received was also generally positive. “I knew the play would be very difficult to watch and that it would be accompanied by many tears,” wrote Marilyn Telowitz, a schoolteacher who had taught near Ferguson. “But the experience was so true and so beautiful, as well as so emotional, that we had to go out and talk about it afterward in order to fully process it. So few outsiders had any idea about any of it, even when they came to Ferguson, and Orlandersmith got it!”

Unfortunately, ticket sales were low for Until the Flood, especially compared to the blockbuster musical Follies, the production the Rep did right before. This is not too surprising, as after two years of hearing about Ferguson, many in the city are tired of the topic. “We knew it was going to be risky,” Woolf admitted. “But we thought it was a conversation worth having. We didn’t expect a runaway bestseller in terms of seats.”

And there were complaints. One patron, in an email to Gordon, likened the play to a sermon. It was not meant as a compliment: “Just thoroughly disappointed (actually disgusted) with that play,” wrote the patron. “We try to avoid this subject from the news media, because everyone has their own opinion about it and it is not going to change people.”

For her part, Orlandersmith doesn’t read reviews, and shrugged off notes of negativity. “There’s always going to be someone who wants their own individual sense of justice at the expense of someone else’s truth,” she said.

Ultimately Until the Flood did not provide any one group with a sense of justice or closure. It did not recount current events, or examine the racially biased policing practices unearthed by the U.S. Department of Justice in St. Louis after Ferguson. Instead, the play was a simple act of listening and speaking—of listening to people who were not talking to each other, and then getting an audience to listen with her to perspectives they hadn’t considered, refused to hear, or felt were distasteful. For 70 minutes, audiences listened, and people—some people, at least—were finally able to hear each other.

Gordon says he saw the power of that listening during the play’s run, as audiences would linger in the lobby after the show, reading the displays and chatting in small groups about what they’d seen. There were usually some tears. “This was definitely the right thing for us to do,” Gordon concluded.

Rosalind Early is the associate editor of the alumni magazine for Washington University in St. Louis and a freelance theatre critic for St. Louis Magazine.