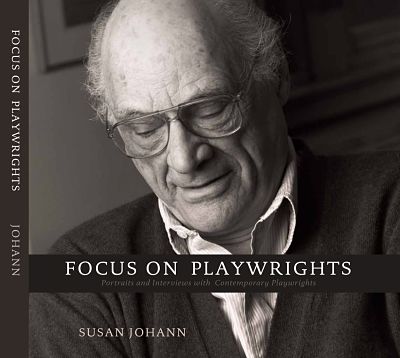

“Old school” is not a term Susan Johann uses for her work, but it seems fitting for this veteran portrait photographer, whose iconic images of playwrights—typically intimate, often contemplative, occasionally playful black-and-white portraits—have for more than 20 years crystallized these writers’ personalities in the pages of American Theatre and countless other publications with an elegance that brings to mind the names Avedon, Beaton, Leibovitz. Not that her work is derivative; as she detailed in a recent interview, the look of Susan Johann portrait is distinctive for a number of reasons, some technical, many dispositional.

The occasion for our conversation was the publication of her beautiful new coffee table book Focus on Playwrights, the product of years of shooting that began in 1989. The book also contains a number of illuminating interviews with her subjects.

You were the official photographer for Signature Theatre, is that right?

I was. But that’s not how the series started. [Signature founder] Jim Houghton was a client of my husband, who did taxes for the arts, and I had my photo studio right next to his office. Jim saw my picture of Edward Albee and of Wendy Wasserstein and he said, “You know, we need some photos taken for brochures” and the like. I remember he asked me: “How is Albee? I hear he’s difficult.” I told him, “He’s not difficult. He’s one of the most important people in the arts, as far as I’m concerned.” I had probably done about 30 playwrights in the first two years by the time Jim saw my work. Jim O’Quinn [founding editor of AT] saw it around then too.

So how did the project begin?

I was asked to do a picture of Chris Durang, and it just took off from there. As photographers, we always look for subjects, and playwrights seemed to be underrepresented. Having them all in one place appealed to me, so I started planning an eventual book. Besides, I wanted to meet Arthur Miller and Edward Albee.

How do you get the photos you get?

If you know their work, you speak to what you think is their interest. As opposed to actors, who are used to putting on a face, once you engage a playwright, a person who’s a thinker, on a subject, you can elicit their self—their real self. With actors, you always have to please them, to give them the picture they want. But with playwrights, if you get them talking about things they’re interested in… Anna Deavere-Smith, she’s almost a sociologist, and she’s so interested in all of society, so just about anything gets her going. I remember David Hare was doing Via Dolorosa on Broadway when I shot him, so I talked with him about that. Also, he delves so deeply into family; we started talking about Secret Rapture, and then we got into stories about our kids. It was able to get him in his depthful part, and get him laughing. You can really reveal something about these people, so the audience could look at it and understand something more about this person. That was my goal.

How have playwrights responded?

Tina Howe sent me a note, “Thank you for making me look like someone I know.” On the other hand, some playwrights—I can’t say who, but one of them told me, “I don’t like this picture, it’s too intimate.” And I thought, “Ooh, I really caught something.” But people don’t always want to be revealed.

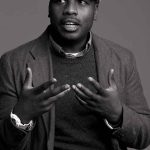

Photography can bring us in, because of a choice of a lens, and allow a person to emerge. It’s not: “Turn left, chin down, cross your arms.” I never did that. I never told anybody what to do. They all found much more interesting things to do than I ever would have thought for them to do. In my picture of George Wolfe, he has one hand under his head, the other over it, and I told him, “Don’t move!” I may say that. I asked him why he did that and he said, “I have to do this, otherwise my head’s going to fall over.” He’d had an opening the night before.

If all else fails, I get ’em on the floor. The closer to the earth we get, the more relaxed we are; it’s also a different position than you normally sit.

Do you shoot in a studio?

No, I would just have a backdrop, one light, and an assistant. I try to be simple. With Arthur Miller, I didn’t take the backdrop; I just went to his apartment.

You mention the choice of lens. Can you tell me more about that?

They’re very deliberate choices. The 50mm lens, which is what would come on a camera, will give you from hips to head, and you can move back and get the whole body. But if you want to get real close without intimidating your subject or distorting their features, the best portrait lens most of the time is a 105. I also use a 180: I’ll be about three feet from a person, and the eyes are in focus but nose is it out, the ears are out. So you really focus on their eyes. The Albee picture is that, and the George Abbott picture; probably Wendy Wasserstein. The 105 was good for Suzan-Lori Parks because I wanted to get her hands; she’s such an active person.

That’s one thing people say: “Susan Johann’s pictures have a lot of hands in them.” Well, we talk with our hands. Actually, sometimes I did pictures just of hands and feet. Craig Lucas wore the most funky, beat-up tennis shoes you’ve ever seen. I thought of just doing pages of just hands and feet of playwrights, with a little key to who’s who.

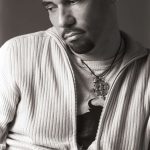

What do they typically wear?

I tell people to wear what they would wear to rehearsal. Then in came August Wilson in a three-piece suit. He had a really strong sense that he was a model for the African-American community. He came in as though he was their icon—he was very conscious of that. He wouldn’t smoke. I love smoking; you see lots of smoking in my photos, the curls of smoke. It also lets you see people’s hands. My mother smoked, so I was used to having it around the house. I never did, but I would get a contact high from it.

August told me things: He was the easiest interview I ever did, because he talked in stories. I asked him how he started writing and he said, “Her name was Nancy Arlen and Nancy Arlen was the kind of seventh grader even the third grade boys were in love with. I started writing poems for Nancy Arlen and leaving them on her desk.” I was like: I don’t have to do anything, just let him talk.

Did you usually interview them at the same time you did the photo shoot?

No, everyone I sat down with separately or did a telephone interview. I did one by email, Sarah Ruhl, because she was too busy. Marsha Norman was also very easy to interview. It’s an oral tradition, she said, from the South. If I’d had more time and my druthers, I would have interviewed every single one. But I realized the book was a hard sell. If I’d been interviewing novelists, it might be different; the book publishing world would like to read about itself. Every field wants to look at itself. It’s like with La La Land: Hollywood loves lookin’ at itself. A love story about L.A.? Yeah, we’ll do that.

Apart from the obvious big names, how did you seek out your subjects?

I would go to places like the Contemporary American Theater Festival and take pictures of the playwrights. Some would be sort of minor playwrights who later became major. Chris Durang, when I took him—I don’t think he had more than one play or two. He had Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All for You, which made people pay attention. And then he just took off, and I thought, “Oh, I did it right.”

The year I took Albee’s photo, everybody had written him off. It was before Three Tall Women, it was before his season at Signature. He was 65. When I would tell people, “I got a picture of Edward Albee,” they would say, “Oh, he hasn’t written anything lately, has he? Virginia Woolf was a long time ago.” And I would say, “What if he wrote Virginia Woolf now?” That was one of the things Edward said to me: We don’t know who we’re going to care about in 100 years.

You’ve got a lot of major folks very early in the career. I almost didn’t recognize John Patrick Shanley.

Donald Margulies told me that—he said, “I’m amazed how young we all look.”

You’re not done shooting playwrights, right?

Oh no. I’ll be in New York next week to shoot Eric Bogosian.

In the time period since you started, the technology has changed. Do you still use the same set-up?

I still shoot the same set-up, but now I shoot both digital and film. I use the same film I’ve always shot with, though I can’t get it anymore, so I’m going to run out.

What kind is it?

It’s called Technical Pan; it’s a very fine-grained Kodak film. It was made for technical photographs, to take photos of the insides of machines. It’s a very slow film, which means you need more light and a faster shutter speed. But it’s a beautiful film; the fall off of the light is dramatic, but you get a lot in the shadows. And it’s very fine-grained, so could blow it up as big as a wall.

You look at the Horton Foote photo: You see a lot of information in the dark, but it’s all quite bright in the light. That film also means that I lose shots a lot of times; when people are moving, they go out of focus. With some of them, I had about an inch depth of field, and if they moved they were out of that.

And do you always shoot in black and white?

I love black and white; it heightens. You almost see the emotions more clearly, I think. I think color is beautiful—I use that too. My friend and mentor, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, told me, “I hope you’re shooting color too. They’re going to ask for color.” I said, “Oh, should I?” So now I do it at the same time. Pull a color picture. But the idea of the book was always black and white. It’s sort of like abstraction in some way; we see the planes of the face. We see something different, I think.