As we enter a period of uncertainty, to put it mildly, one of the areas most at risk is the federal funding of arts and culture. It’s no surprise to hear that the social conservatives and free-market extremists now in power are already making noises about implementing their long-held dream to eradicate the NEA and PBS.

What happens, then, when the faucet is turned off? What are the priorities, how do funds get allocated, and to whom?

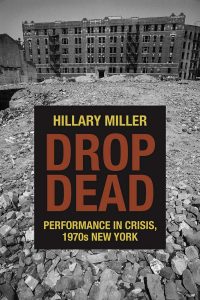

Our current predicament makes Hillary Miller’s Drop Dead: Performance in Crisis, 1970s New York an especially fascinating read. Of course, circumstances have changed dramatically since the era Miller writes about. While many people fiercely battle public funding for the arts, a great number of municipalities and states have also come to acknowledge that this funding can hit a sweet spot of economic engineering and prestige building, and as such deserves to be maintained (up to a point, of course—this isn’t Europe we’re talking about). It’s also interesting to read this new book alongside last year’s Razzle Dazzle by Michael Riedel (my former colleague at the New York Post), which looks at Broadway’s recovery from its 1970s doldrums and its evolution into a money-minting tourist magnet, thanks in large part to the city’s success in “cleaning up” Times Square.

Miller, an assistant professor of theatre at California State University, Northridge, zeroes in on a period of when arts monies ran dry in New York City—not so much because of an ideological appetite for destruction, as is the case now, but because the city’s coffers were empty. The book’s title is borrowed from a notorious Daily News headline attributing those words to President Gerald Ford, though they actually were a paraphrase of his initial refusal to help rescue the near-bankrupt city.

While the writing can trip on itself—if there is a way to make a point directly, this academic book sometimes seems to willfully avoid it, with a particularly leaden introduction—Drop Dead does make for a fascinating read once it finds its groove. Miller breaks down the action into chapters focusing on an institution or personality as they were in the 1970s; together, they capture a turning point in a nexus of culture, money, community (born of either neighborhood or shared bond), and real estate.

The background, which is weirdly exotic to read about from the perspective of our current time, when New York can feel like a cynical boomtown, is one of decrepitude. It’s a context in which someone like Roger Starr, a Housing and Development official in Mayor Beame’s administration, could recommend “planned shrinkage” for the city—that is, letting disaffected neighborhoods pretty much die on the vine. Natural causes, if you will. In this environment, what happened to theatre?

Some of the chapters, like the one on Ellen Stewart’s La MaMa E.T.C., cover ground that’s relatively well-known by most people with an interest in New York’s experimental scene. Others look at individuals who made a huge mark at the time but whose names are mostly forgotten outside of theatre circles, like Vinnette Carroll and her Urban Arts Corps. The company, which trained actors and toured the boroughs in the 1960s and ’70s, played in parks and housing projects, and grew in influence until Carroll scored unlikely Broadway hits with her musicals Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope (1972) and Your Arms Too Short to Box with God (1976).

Most fascinating are the stories of theatre companies whose “leaders began careers at social service organizations, day care centers, and high schools.” Imagine that: not an MFA in sight! This allows Miller to bring up the tricky subject of the critical evaluation of such forms as street grassroots, and community theatre, often derided for their good intentions but not necessarily high artistic quality. Those companies don’t thrive in New York anymore, but the issue of judging a play based on its intentions or its checking certain representation boxes remains a tricky one.

Similar ambivalence can be found in the chapter about the Everyman Street Theatre, which worked with neighborhood youths and “turned away no one.” The chapter peaks with the description of Everyman’s eye-popping 1973 collaboration with Peter Brook and his company, then in residence at BAM, and which on that particular trip included “Helen Mirren, an English blonde with an important film or two to her credit,” according to a report in the Christian Science Monitor.

Some of the terrain Miller covers is particularly interesting to consider in tandem with Riedel’s book, especially when she looks at the “philosophy of cultural upgrade as a path to economic revitalization.” Indeed, the late ’70s saw the emergence of the idea that theatre might not be a drain on the city’s coffers, but actually help fill them—a school of thought that still holds today, with theatre as an economic engine on a par with tech (something has to replace manufacturing, right?). The transition into New York City as both culture capital and “entertainment center,” and thus worthy of being saved, took hold then, but there was a price to pay. One of the drawbacks, as Miller puts it, is that this also meant a shift in focus, with culture now intended to serve the city as a whole (translation: to serve white, well-off audiences, often from out of town) rather than “its individual communities.”

This evolution is illustrated by the latter chapters, which shed an interesting light on fairly familiar people/institutions: Joe Papp and the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). These chapters are the most fluidly, incisively written, showing perhaps that Miller is more comfortable with the subjects (and with being pointed about them), as opposed to her treading a little more lightly when dealing with black or Latino creators and their efforts.

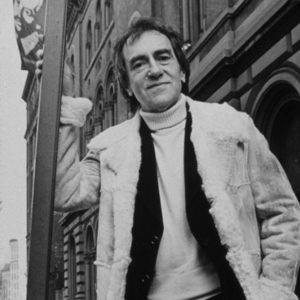

Miller is very engaging on both Papp’s efforts to strike a deal with the city over the Astor Library (the current Public Theater) and his doomed run at Lincoln Center, because those episodes are at the very crux of the dialectic between commerce and art, audience and creation, community fostered by a common spirit (theatre!) and community fostered by class, race, sex, or neighborhood. This essentially boils down to: Who owes what to whom?

Papp argued that his theatre provided a “public” service, in every sense of the term, and so the municipality should fully support it by purchasing the Astor Library, then leasing it back to the Public for $1. For his first attempt at convincing the relevant authorities, he enrolled an array of artists and celebrities, only to see that line of argument backfire; chastened, he bused in people from the boroughs to the next hearing. Of course, the Public had already muddied the waters of its purported mission (free or at least accessible culture, as necessary to New York as garbage removal!) by venturing into commercial producing with Hair, with A Chorus Line to follow in the mid-’70s.

More muddying happened when Papp added the Lincoln Center job to his portfolio. He presented black and Latino playwrights and directors to the subscription audience, which would not have it, to say the least. Papp gave up the Lincoln Center gig after just a few years.

Papp was a lightning rod in countless ways, and this programming kerfuffle is only one of them. His insistence that the city needed to invest in arts infrastructure was another, and it still bears fruit today, manifested in the appetite of donors for fancy new buildings bearing their name, and to hell with operating budgets or unglamorous pursuits like neighborhood projects! (Miller reminds us that in 1971, when the city spent millions of dollars on the Astor Library purchase, “It gave $350,000 to all neighborhood arts programs combined.”)

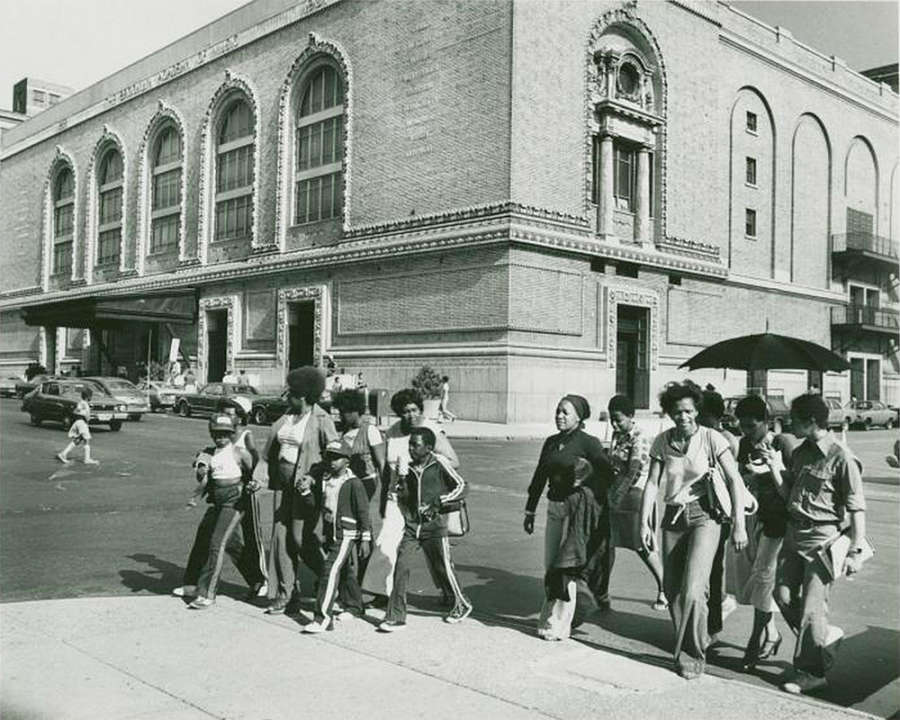

The example of BAM is another salient one, especially since its leader, Harvey Lichtenstein, had one more hurdle than did Papp: He wasn’t in Manhattan but in Brooklyn, whose ’70s image was stuck between the deterioration of neighborhoods such as Crown Heights and working-class strongholds like the one depicted in Saturday Night Fever (whose characters thought of Manhattan as an impossibly remote land).

The aforementioned conflagration of theatre, money, and real estate reached its natural apex in the late ’70s, with the slow revving up of the centrifugal force that would eventually redistribute attention and population away from Manhattan and into Kings County, and turn BAM from outlier to establishment. This also meant the forcing of a conversation about the meaning of community, and how theatre can best represent it, serve it, deserve it. It’s a conversation those of us concerned with theatre, New York City and the public spirit, whatever that may be, still have, and will probably have anew in the next four years.

Elisabeth Vincentelli is a critic and writer based in Brooklyn.