We keep our eyes on the iPhones they’ve given us as we walk the streets of Shanghai searching for a missing college student who has been kidnapped. She is reportedly an Internet celebrity who likes to text and post photographs online; we are her estranged sister, searching for clues to her whereabouts from her online fans. We are ushered past a café called Midnight Burger, where we get a discount card for a meal, then onto one of the three campuses of the Shanghai Theatre Academy, with its huge billboard of American acting teacher Sanford Meisner.

We are brought into a dorm, rushed up and down elevators, in and out of dorm rooms, and into a darkened staircase. There we confront a young man our sister’s fans have fingered as a suspect in her kidnapping. He cowers wordlessly in the well, while his recorded voice chatters away in our iPhone earbuds. We realize he’s innocent. As we hunt down other clues supplied on the iPhone screen and meet various classmates of our sister—hearing their recorded comments in our headphones while the characters in person stand next to us, expressively but mutely—we learn that our sister’s drive for fame has made her some enemies. Eventually the clues lead us to the school’s roof, which is cluttered with our sister’s belongings—and a note from her explaining that she faked her kidnapping to goose her online following. And now she will disappear from our lives.

Duality, a theatre piece entirely in Mandarin, was commissioned by the Shanghai International Arts Festival for the fifth anniversary of RAW!, or Rising Artists’ Works. The fest, now in its 18th year and referred to in English as CSIAF, is the largest gathering of its kind in the People’s Republic of China, and it’s as daring as it is large. As Rachel Davies of Storybox said of CSIAF’s organizers, “They are willing to take risks to be at the cutting edge; I really admire this.”

All the performers in Duality are students at the Shanghai Theatre Academy, a public university founded in 1945, and the director, Tong Tong, a mainland Chinese theatre artist and filmmaker who attended New York University, is now a graduate student at STA. The show was created in collaboration with a New Zealand theatre company called Storybox, adapted from their immersive work, The Woman Who Forgot.

CSIAF is a month-long torrent of public performances, exhibitions, workshops, and arts classes for the masses, as well as a forum and performing arts fair geared toward the international arts community, taking place in theatres and conference rooms throughout Shanghai. “Some 750 people from nearly 50 countries are attending the forum this year,” CSIAF vice president Li Ming said at the welcoming reception aboard a boat cruising down the Shanghai’s Huangpu River. The event took place between the Puxi side of the river, lined with the dramatically lit 19th-century European-style buildings along the Bund, and the Pudong side, with its overwhelming array of recent skyscrapers, including Shanghai Tower, completed in 2015.

But as sprawling as it is, the Shanghai festival is arguably the most compact way to glimpse what theatre artists are up to these days in China—or at least those artists in China who are involved in international cultural exchange. As CSIAF official Roger Chen explains, the festival’s aim is for the world to know Chinese performing artists, and for those artists to know the world. Among the audience members participating in Duality were two members of Punchdrunk, the British troupe that created Sleep No More and many other works that have led a trend in Europe and the U.S. for what’s commonly called site-specific immersive theatre. They weren’t just in Shanghai to speak at the festival; they’ve also recently taken over an abandoned building in West Beijing Road, renamed it the McKinnon Hotel, and brought a Chinese adaptation of Sleep No More to Shanghai.

“For Chinese audiences now, if you want to watch Sleep No More, you don’t have to go all the way to New York City,” said Hang Chen at the festival’s forum “investment session.” Chen is the CEO of the China Culture Industrial Investment Fund Management Co., Ltd., an investment firm based in Beijing with a specialty in art and culture. In a PowerPoint presentation, Chen listed immersive theatre among the rising trends he saw in Chinese theatre, including:

- Innovation in stage technology, such as the incorporation of virtual reality and augmented reality.

- The crossover of content from the stage to the screen (both movies and television) to gaming, and back again. (This is already happening: Tomb Raider is the title of a popular Chinese play at the People’s Grand Theater on Jiujiang Road.)

- The Internet, meaning not just the availability of online tickets but the investments that Internet companies are making in performing arts companies.

Chen sees theatre as a growth market: Professional theatre in China generated the equivalent of more than a billion U.S. dollars in revenue in 2015, Chen pointed out, a nearly 7 percent increase from the year before. After Chen’s presentation, Chencheng Ma of SMG Live, Punchdrunk’s Chinese partners, explained the eight-month effort to get Sleep No More ready for the public. The show has a cast of both international and Chinese performers; the film noir atmosphere of the original has been relocated to Shanghai in the 1930s. As with its New York City counterpart, Chelsea’s McKittrick Hotel, he expects the McKinnon to be a new cultural landmark with a fashionable restaurant, a boutique hotel, shops, and a “VIP club.” If such entrepreneurial optimism sounds out of scale, consider that the show had already racked up the equivalent of a million dollars in advance ticket sales a few weeks after the box office opened for business, a month before the show began.

The session concluded with a series of pitches from five entertainment companies seeking investment, or trying to get gigs, or both. Four were from overseas, including Storybox and NYC’s 3-Legged Dog Media + Theater Group, which presents high-tech theatre pieces in its downtown Manhattan venue, 3LD Art and Technology Center. The company also partners with corporations to produce commercial videos and installations that generate revenue for its nonprofit theatrical endeavors. It might be too simplistic to see what 3LD has been doing—with its mix of avant-garde and high-tech, its partnership with commercial interests—as offering a rough model for Chinese aspirations in the performing arts. But Kevin Cunningham, 3LD’s artistic director, did tell me, “Five years ago, the Chinese weren’t interested in what we do.”

That was then. Chen Qiang (English name: Frank Chen) was in the audience at the investment session. Chen is an executive with the Shanghai Live Dream Culture Development Ltd. Co., which is constructing a cultural center in the Jiading District, a suburb of Shanghai. “We’re building three theatres which will focus on immersive theatre, interactivity, and technology. We are interested in attracting the generation born in the 1990s, and the key word for that is interactivity.” His company is a private one, though with backing and partial ownership by the state. “Private companies who have to survive in the market,” he said, “will take the lead, with government support.”

In his presentation at the investment session, Hang Chen made clear that cultural exchange goes both ways. “We’re very pleased,” he said, “that there is more and more [Chinese] product for the international market.”

Some of that product was on display at “Pitch Session II: Going to the World!,” for which 10 performing arts presenters from around the world had selected 10 Chinese productions (out of a possible 55 works of theatre, dance, music, and puppetry) that they deemed most likely to draw audiences on an international tour. A representative from each of the chosen productions showed videos of their work, then talked about it, followed by feedback from the arts administrators, sometimes about the videos (“Too choppy; it’d be better if we could see some of the complete choreography,” said Rachel Cooper of the New York-based Asia Society, one of four Americans on the panel of judges.)

Half of the productions presented were modern dance, one of which, Fault Lines, chronicled the 2008 and 2011 earthquakes in Sichuan and Christchurch, respectively. “The performers all had friends or family who had died in an earthquake,” explained Lyu Yong, general manager of the company, which was a joint production with New Zealand and Australia. “The Ministry of Culture is interested in this work,” Lyu said as part of his pitch, “and we will be able to cover the cost of our flight.”

Some of the exchanges between arts administrators and artists would sound at home in the U.S. After a presentation of contemporary dance pieces by BeijingDance/LDTX, Thorsten Teubl, a dramaturg and deputy director of the Kassel State Theatre in Germany, asked about the company’s plans. “We want to emphasize diversity,” replied Yin Peng, the company’s project coordinator.

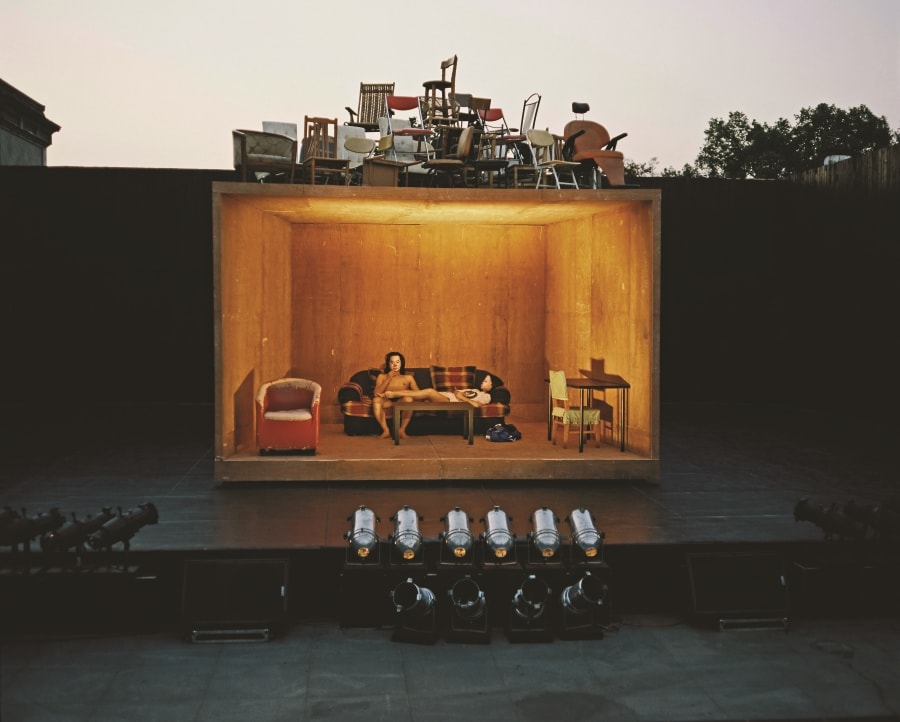

Other productions offered social critique, of a sort. A Man Who Flies Up to the Sky from the Beijing-based New Youth Theatre Group consists of some 40 mute and often eerie scenes, each lasting only a couple of minutes, all taking place within a box of a set that suggests a boxed-in existence. Eight performers wearing masks portray more than 30 characters, from a lonely woman seeking solace with Siri to a boxer forlornly removing his gloves, while a six-man orchestra stares blankly at the audience. Director Li Jianjun explained how the lives depicted onstage had been shaped by “the haste of China’s modernization and the power of its political system.”

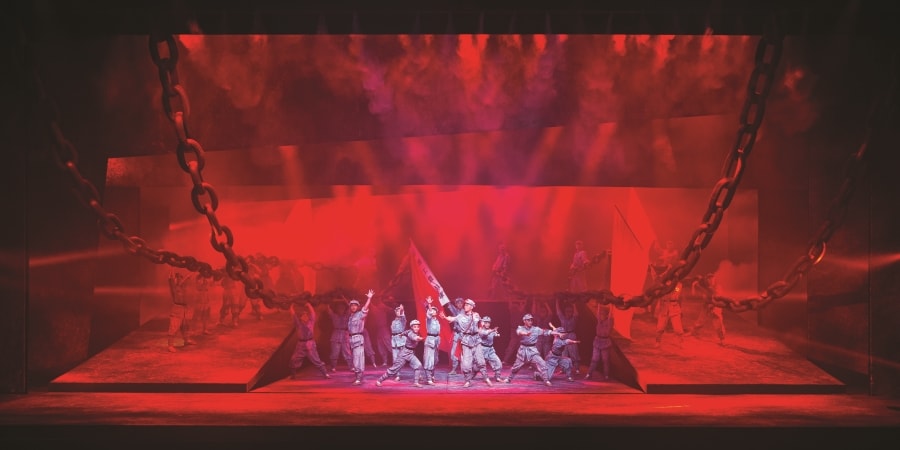

Some of the productions selected for the pitch session involve traditional Chinese opera, though not in any traditional way. One, with the complicated title “I” Fantasie—Rencontre Between Debussy and Du Li Niang, was given a full production that week. Combining Kunqu Opera—a form from the Shanghai region that predates Beijing Opera by hundreds of years—with the music of Debussy, as if a fictional Chinese heroine from the classic The Peony Pavilion had been cast as the lover of a French composer, the hybrid work by Gu Jieting may not be a completely accessible stage narrative, but it incorporates some dazzling stage design alongside state-of-the-art video projections.

That was just one of a series of East/West hybrid works offered to mark the coincidental 400th anniversary of the death of both William Shakespeare and of the Chinese playwright Tang Xianzu. CSIAF also commissioned celebrated Kunqu Opera star Zhang Jun to create a “one-man contemporary opera” that combines the work of both authors, a piece he has titled I, Hamlet. “It does not represent the tragedy of the Prince of Denmark,” Zhang Jun explained at a separate session. “Yet it recreates the anguish of Hamlet.” The work incorporates singing and acrobatics, as well as dialogue, some of which is the Bard’s. “At the beginning and end, I have to speak English, which is very tough,” Jun confessed.

I later asked American playwright David Henry Hwang about this artistic effort at bridging cultures; he has never attended the Shanghai festival himself but has written about the clash of Western and Chinese cultures in such plays as M. Butterfly and Chinglish. “The desire to create hybrid East/West theatre forms has existed for some time in China,” he told me. “I believe these efforts have yet to feel fully satisfying to audiences in either culture, due largely to the gulf which continues to exist between these worlds. Similarly, China has also tried to create its own Broadway-style musicals for more than a decade now, without much success. I believe these distances will eventually be bridged, and that the current experiments in collaboration are steps in the right direction.”

One dissatisfied customer was judge Scott Stoner, vice president of programs and resources for the U.S.-based Association of Performing Arts Presenters (APAP), who told me at the end of the pitch session that in almost all the works he had seen, whether dance, music, or theatre, “There appears to be heavier emphasis on technique and technical skills, and the visual spectacle, than on the kind of narrative that is needed to engage Western audiences.” Still, Stoner was impressed with the dance pieces, noting, “It’s interesting that with our own APAP|NYC pitch sessions, many of the strongest applicants are from the dance world.” He especially liked A Man Who Flies Up to the Sky: “It is the type of work that could be placed in any community and would be truly engaging for a wide range of audience members.”

Five short stops on the Shanghai subway’s 1 line take you from the Shanghai Museum, which displays the 16th-century wooden Tujia masks used for Nuo Opera, to the Metro City shopping mall, with its airy, glistening atrium inside a giant glowing globe, lined with Starbucks, dozens of other stores, and teenagers wearing shirts with English words on them; one I spotted said “Smile Eat Kiss Laugh Talk Drink.” On the mall’s fifth floor, a former cinema has been transformed into Theater Above, a 699-seat live venue that hosted a CSIAF-commissioned puppet show, Papa’s Time Machine. Its creator, who goes by the name Maleonn, teamed with artists from Hungary and Germany to create intricate human-sized puppets to tell the story of a son who tries to overcome his father’s Alzheimer’s by inventing a machine that will help him preserve the memories of their happy times together.

Theater Above was founded by Stan Lai, one of Mainland China’s most celebrated theatre artists, though he was born in the U.S., educated at Berkeley, and is based in Taiwan. The author of some 30 popular Chinese-language plays and the cofounder in 2013 of the Wuzhen Theatre Festival, Lai likes to tell reporters that too much theatre in China is housed in fancy new “temples” increasingly built away from city centers. “Theater Above is the model for the 21st century,” he told Time Out Shanghai when the venue first opened in the mall, a place where people can shop, have dinner—and see a show. “Theatre,” he reasoned, “becomes part of their lives.”

A year later, Lai told The New York Times that he finds it “unfortunate” how commercial Chinese theatre has become, how the Chinese “see theatre as a lucrative business plan, as crazy as it sounds. I say crazy because in the U.S. it would never happen.”

Jonathan Mandell, a regular contributor to this magazine, was invited to CSIAF to give a talk on immersive theatre.