Divas of different eras, Mary Martin and Barbara Streisand were both immediate Broadway sensations. Both also gained national prominence through television specials. And though neither was considered conventionally beautiful, both became fashion leaders. Two new biographies, David Kaufman’s Some Enchanted Evenings and Neal Gabler’s Barbra Streisand, offer the rare chance to compare and contrast two of the 20th century’s most indelible leading ladies, whose debuts encapsulate two very different Broadway eras.

As personalities, as well, the two couldn’t have been more different. Streisand was a deeply wounded child whose mother begrudged her daughter’s success until the end of her days. Martin led a charmed life from the very beginning: She was born into privilege in northern Texas and doted on by a father who opened a chain of dance studios when young Mary expressed interest in teaching, then sent her off to L.A. in a yellow convertible when honing her own hoofing skills seemed like a better idea.

A petite tomboy with a large-featured face, Martin was never destined to become a film star. After a couple of frustrating years in Los Angeles, she left for New York, where she immediately had better luck: In her second week in New York a manager who had signed her in Los Angeles put her front of Bella Spewack, Sophie Tucker, and Cole Porter. Martin had no idea she was auditioning for a Broadway show. Asked if she’d ever been on the stage before, she gave a typically hopeful answer: “Whatever it is, I know I can do it.”

It took just one song in the otherwise forgettable Leave It to Me! for Martin to make what one critic would call “the most starry overnight debut in the history of Broadway.” Dressed in not much more than a white fur jacket, she performed a near striptease while singing “My Heart Belongs to Daddy.” Porter was convinced Martin that never really understood the song’s implications, calling her the most naïve person he’d ever met.

Trying to capitalize on her newfound notoriety, she returned to L.A., only to find her star effectively grounded; as a contract player for Paramount Pictures, she appeared in nine undistinguished movies. Film suppressed Martin’s natural quirkiness and sparkle. It would be the smaller screen and musical material that would bring her to national prominence, as in the 1950s she became the first lady of television specials, from musical revues to Peter Pan, a title role she reprised in two separate television productions, and the role with which she would thereafter be most identified.

Far from holding her back, though, Martin’s genuine innocence served her well throughout much of her career. While she struggled in shows that required a sexier presence, including One Touch of Venus and The Skin of Our Teeth, the sunny charm of this cockeyed optimist infused her Tony-winning triumphs as Nellie Forbush, Maria von Trapp, and of course, J.M. Barrie’s green-stockinged sprite. Small wonder the latter role was Martin’s favorite; like Pan, she was a perpetual child who admitted to never wanting to grow up.

To some extent, though, what made Martin’s career possible was her micromanaging agent, advance man, hairdresser, and husband of 33 years, Richard Halliday. A gay man addicted to alcohol and amphetamines, he made enemies of nearly everyone he worked with. But with the help of a designer named Mainbocher, he turned plain-Jane Mary into a glamorous legend. While Halliday carried on open liaisons with men, Martin was more discreet—except around Janet Gaynor, with whom she appears to have had more than a friendly relationship.

A diva who rarely acted like one, Martin kept to herself backstage, in part due to Halliday’s vigilance. Her relentlessly cheery memoir, My Heart Belongs—a best-seller—indicates just how careful she was to cultivate the image of the bright and buoyant all-American star. She needn’t have worked so hard at it; her friend Hedda Hopper claimed that Martin had no enemies, and her relationship with audiences and critics was nearly unanimously joyful.

In continual physical and vocal training, Martin was legendary as a consummate trouper. Praised by Richard Rodgers for never giving a performance that represented anything less than the best that was in her, she toured with musicals to Japan and Vietnam, performed with severe injuries and ailments, and missed just one performance in the 26-month run of The Sound of Music. If Martin’s voice was a wonder, her work ethic was superhuman.

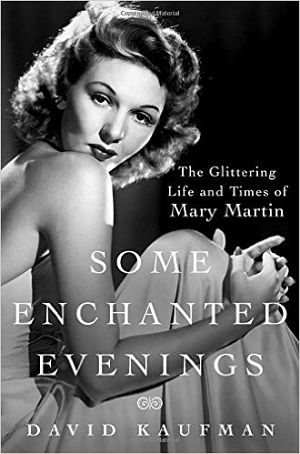

David Kaufman’s amiable and thoroughly researched Some Enchanted Evenings portrays her marriage to Halliday in evenhanded detail. With its minute attention to the couple’s extravagant lifestyle—notably their Brazilian getaway, which turned into an enormous working farm—the book occasionally loses its pulse. Kaufman also struggles to define the essence of Martin’s technique and appeal, as in: “Every performance was the same only to the extent that it was different.” Exuberant charm and a voice as big as Merman’s were undoubtedly her stock in trade. But despite its flaws, Some Enchanted Evenings does an important service in reviving the legend of one of the century’s great theatre stars.

Indeed, there’s no telling how many more Tonys she might have won had Martin and Halliday selected stronger projects. With her Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm quality—as Noël Coward pegged it—Martin was often drawn to lesser plays and musicals long on sentimentality, among them Kind Sir, Legends, and Do You Turn Somersaults. She famously turned down the part of Eliza Doolittle, and her choices in 1963 were particularly unfortunate: Martin signed on to a misbegotten musical about Laurette Taylor called Jennie after passing on both Hello, Dolly! and Funny Girl. The latter move, though, essentially paved the way for a fiery new comet in the New York night.

Among the ushers for Martin’s run of The Sound of Music at the Lunt-Fontanne theatre was an 18-year old from Brooklyn who was also developing a downtown cult following as a torch singer. Soon graduating to a better grade of nightclub, Babra Streisand—who had already by then dropped the middle “a” in her given name, Barbara Joan—began attracting the attention of Broadway casting directors. Claiming to hate singing, calling it “a floozy job” and merely “wind and noise,” Streisand wanted to be a great actress, “like Duse,” as she put it. Still, audiences were disarmed by the raw intimacy of her singing. Her acting ambitions surely contributed to her mastery of song interpretation; the composer Jule Styne said she was the first vocalist he’d heard who was a great actress in every song.

At 19 she appeared twice on “The Tonight Show,” and in 1962 she made her Broadway debut in a role she was much too young to play, as a middle-aged lovelorn spinster in I Can Get It for You Wholesale. Audiences didn’t seem to notice: On opening night Streisand’s solo commanded a three-minute ovation. It would also garner her a fee of $5,000 a week on the nightclub circuit and a raft of television invitations. At age 20 she recorded The Barbra Streisand Album, which would make her the bestselling female vocalist in the country. A year later she won a Grammy and signed a 10-year, $5 million deal with CBS for television specials.

The dizzying whirl of early success would culminate with Streisand playing a role for which she was again apparently too young, and again succeeding in spite of it. In what critics cited as one of the great leading lady debuts, Funny Girl made the 22-year-old Broadway royalty. She appeared on the cover of Time, and Life called her “Cinderella at the ball, every hopeless kid’s hopeless dream come true.” It also marked her last appearance on the legit stage.

What fueled this locomotive of fame? Was it the high school choral director who rejected her audition? The stepfather who labeled her a beast? A jealous mother who, after observing her daughter at an acting class, said no one would ever pay to watch her onstage? Or was it a matter of a self-described ugly duckling and loner desperate to fill the hole left by a father who died when she was a toddler? Whatever the motivation, Streisand possessed an unwavering awareness of her own talent and a fundamental craving for fame. Success would be her revenge.

Gabler locates Streisand’s primary obstacle in “the double whammy of Judaism and Brooklyn.” If Brooklyn meant baseball, boredom, and bad breath, as Streisand was purported to have said, it also gave her the resilience that often characterized the borough’s denizens. Despite a lack of religiosity, Streisand’s personality and her two Broadway successes traded on her obvious Jewishness; in fact, in Gabler’s estimation she was the first star to succeed because of her Jewishness and not in spite of it (which might be news to the subject of Funny Girl, the unapologetically Jewish comic Fanny Brice).

And no attack on her famous nose—whether from neighborhood kids who called her “Big Beak” to Variety’s early advice that she needed a “schnoz job,” to critic John Simon’s relentless onslaughts—succeeded in making Streisand surrender her physical identity. The classic irony was that this so-called plain girl became a style trendsetter, as her Nefertiti look sparked sales in short wigs.

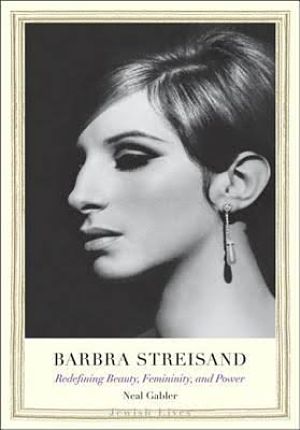

If there are few original ideas in Barbra Streisand—Gabler’s wing-woman, Camille Paglia, is quoted no fewer than 11 times—the author does warm to his endlessly fascinating subject, writing with a verve and empathy that make for an engrossing read. Molly Haskell’s thesis that Streisand was nearly always in control of her persona—whether it was the early wardrobe of vintage clothing or most of her choices in movies—is the spine of a book that takes as its subject Streisand the metaphor.

Over the course of her career, the star’s image has been dynamic and complex. Initially she represented the plain girl that guys overlooked, the classic underdog, and a Jewish American success story. As she achieved power, many women regarded her as a proto-feminist who revolutionized gender roles. And as her physical appearance achieved acceptance and even adulation, Gloria Steinem wrote that she “changed the bland, pug-nosed American ideal” forever. Gracing the cover of Playboy, she’d become a sex symbol.

Not surprisingly, Gabler—a film critic and former host of “Sneak Previews”—is particularly astute about how Streisand’s movies worked out her preoccupations, notably the deceptive nature of appearances and the Jewish girl’s attempt to revive the spirit of a Gentile lover who is ultimately the wrong match (cf. The Way We Were and The Prince of Tides). Starting with the film of Funny Girl, power became another important theme in her work, as it would in her life.

As this restless talent started producing and directing films herself, there was an inevitable backlash. Pauline Kael offered a particularly perceptive explanation of the growing resentment: “There is a possible unpleasantness, of threat, in that red-hot talent…which produces unresolved feelings in us.” The response was sometimes thoughtful (Kael), contradictory (Time), or cruel (John Simon again). Quoting a variety of sources, Gabler handles the issue of the star’s reputation for being demanding with a deft hand. Since her first album she’d been known as a perfectionist. Making life difficult for director William Wyler on the film of Funny Girl, taking charge of every aspect of A Star Is Born, Streisand came to be regarded as the epitome of the narcissistic, power-hungry diva. The New York Times Magazine called Star “Hollywood’s biggest joke” nearly two years before its release. When it turned out to be a box-office smash in spite of dreadful reviews, it only amplified Hollywood and the media’s resentment, with one critic callikng A Star Is Born an egregious example of a “star tripping on her own reckless power.” That she also had the gall to enter the political arena by becoming an advocate of liberal causes only stoked the flames.

Carrying so much baggage was a wearying load. For much of the ’70s and ’80s Streisand withdrew from live performance, becoming a recluse and throwing herself into interior design and art collecting. No wonder she would later define fame as “not being left alone.”

But with age has come approval and even worship: Bending the industry to her will, the icon became a deity. There was a Kennedy Center Award, another top-grossing film (Meet the Fockers) and 2014’s Partners, which made Streisand the first performer to have a top album in five separate decades. In what must have felt like the sweetest possible revenge, she recently returned to her old stomping grounds, Brooklyn. In a concert at the new Barclays Center, she met with the kind of rapture that only a deity can command. Said the newspaper of record: “She remains this emblem of volition and charisma and power—the movie star who sings, the singer who acts, the female director who was made to suffer for daring to do what men had always done.”

Michael Bloom is a freelance director and writer and the author of Thinking Like a Director.