David Mandelbaum, artistic director of New Yiddish Rep, admits frankly that mounting Sholem Asch’s God of Vengeance, a 1906 play that explores religious hypocrisy, prostitution, and lesbianism, was in large part a business decision. The timing was irresistible.

After all, Paula Vogel’s Indecent, now heading for Broadway after successful runs at Yale Rep, La Jolla Playhouse, and Off-Broadway’s Vineyard Theatre, is based on the events surrounding Asch’s groundbreaking drama, from its birth in Poland and its evolution throughout Europe and the Lower East Side to its explosive run on the Great White Way in 1923, and beyond.

It was a controversial play—indeed, it sparked a mini-donnybrook—when it bowed at the Apollo Theatre on 42nd Street, not least for featuring the first lesbian kiss on a Broadway stage. The cast and producers were arrested and jailed on obscenity charges.

Set in early 20th-century Eastern Europe, God of Vengeance tells the story of a brothel owner, Yankl, determined to keep his young daughter Rivke virginal, and thus marriageable, at any cost. A boor who nonetheless loves his child, Yankl purchases an expensive Torah scroll, believing it will make him, and by extension Rivke, worthy of respect and admiration. But Rivke is drawn to the prostitutes he employs in the basement, and soon falls in love with Manke, who returns her affections.

The upcoming Yiddish Rep production runs Dec. 22-Jan 22 at La MaMa on East 4th Street, just around the corner from where it opened in 1907. An English translation will be projected onto the set above the actors.

“I knew we needed to do this play, not to draw attention to New Yiddish Rep, but to draw attention to the impact that Yiddish theatre still has for the modern theatre world,” Mandelbaum says. “Obviously it has resonance because of the LBGT movement, and now, after the election, it’s an even more meaningful play. It explores the abuse of women and how a man has grown wealthy through exploiting others and now wants to go legit. Asch’s main interest was religion and the hypocrisy that goes with it. Look, we now have a Bible-thumping VP turning a blind eye to the fact that his boss is an exploiter and abuser.”

Vogel, who won a Pulitzer Prize for How I Learned to Drive and for whom Indecent will represent a long-awaited Broadway debut, couldn’t be more delighted at New Yiddish Rep’s decision to remount the original Asch play. “It’s a play whose time has come,” she says. “Actually I’d like to see playing in repertory with God.” (That’s not in the works, though, for Indecent’s premiere at the Cort Theatre on Apr. 18, 2017.)

Vogel recalls first becoming aware of the play as a graduate student at Cornell. A feminist and lesbian who had just recently come out, she says she was blown away by it. “I kept thinking that in 1906 a young married man wrote this play,” Vogel says, stunned even in retrospect. “He had such compassion for the plight of women. The way of life for everyone was so limited. And then there was the love scene between the two women. I still think it’s the greatest love scene between two women I’ve ever read.”

“I believe that for Asch the love between two women was the purest love that could exist in the world,” says Rebecca Taichman, Indecent’s director and cocreator. “In this play the men are so violent—not that Asch blames any one individual. It’s the whole system that’s corrupt and broken. Pure love can’t exist.” For her part, Taichman will be participating in God talkbacks at La MaMa on Jan. 10 and 17, 2017).

While never widely known, God of Vengeance has never quite faded away, either. In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest. In 2002 playwright Donald Margulies reworked it, setting the action on the Lower East Side in 1923. A production directed by Gordon Edelstein, which appeared at the Williamstown Theater Festival (starring Ron Leibman) and at Seattle’s ACT Theatre, wasn’t well received.

All the artists interviewed acknowledge the challenges of Asch’s original, most particularly its melodramatic, Lower Depths elements and occasionally archaic, wordy language. A Yiddish-speaking production faces another issue: Who’s going to show up? Audiences for Yiddish theatre are limited. Several actors in New Yiddish Rep’s God say they’ve had agents refuse to see their Yiddish-speaking theatre gigs in the past.

Mandelbaum is determined to change all that by offering first-rate productions in Yiddish, including classic works originally written in other languages, that can demonstrate how singularly expressive and modern this old language can be. His Yiddish-speaking Death of a Salesman walked off with several Drama Desk nominations last year, and his Waiting for Godot garnered international acclaim, first staged Off Broadway in 2013, then as the kickoff production at Happy Days Enniskillen International Beckett Festival in 2014.

For God he’s stepping up his game with an unlikely cast that mirrors the world of “otherness” depicted in the play in intriguing ways Asch probably couldn’t have imagined. It includes former members of New York’s Hasidic community, where theatre (what little of it there is) is gender-segregated. These young exiles are now performing in sexually explicit material for secular and gender-mixed audiences—a multileveled transgression. None of these cast members have invited their parents.

The cast also features two respected veterans of the Yiddish underground theatre movement who are not in fact Jewish: Shane Baker, a vaudevillian who grew up Episcopalian in Kansas City, and Galway-born, parochial school-bred Caraid O’Brien, a noted Yiddish translator, theatre, director and actor, in the role of Hindl, the lead prostitute.

Mandelbaum proclaims himself thrilled at the mix, though such diversity is routine for his company; Godot’s Boy, for instance, was played by an African-American youngster who spoke Yiddish. But he is keenly aware of the elephant in the room: God is treading touchy territory. It’s no longer the lesbianism or the religious critique that may be controversial, but instead the way the play may seem to confirm—at least for some theatregoers—anti-Semitic views of Jews as venal exploiters.

The issue is not a new one. When God was produced on Broadway in 1923, American Jews, led by Rabbi Joseph Silverman of Temple Emanuel, were mobilized against it on the grounds that in an era when anti-immigrant and anti-Semitic views were still in the mainstream, the play’s depiction of their faith was offensive. It may strike many similarly today, in a time when neo-Nazi views seem newly ascendant.

But Mandelbaum, who plays God’s most distasteful character, a corrupt rabbi/matchmaker, argues that the issues raised in the play are not peculiar to Jews.

“This play is about ethics, and shows how lovely religious trappings and accessories give people the false idea that they can get around ethics, which is the core of all religions,” he emphasizes. The message too many people take from religion, he says, is that “if you go to confession or atone on Yom Kippur, you get a pass. You don’t have to treat people with respect.”

Eli Rosen, an ex-Hasid making his stage debut in God, agrees. “What’s described here is true in all fundamentalist groups. Does the play suggest that Jews are worse? I struggle with that. But I also believe in transparency. The only way to effect change is to shine a light on what goes on behind closed doors.”

Says Luzer Twersky, another ex-Hasid making his stage debut as the manager of the brothel, “It’s not my job as an artist to worry about who looks good or bad. Anyone who thinks all Jews are good is a fool, and anyone who thinks all Jews are bad is an anti-Semite.”

But O’Brien doesn’t think it’s that simple, pointing out that Asch himself asked producers not to do the piece in the immediate wake of the Holocaust. “He thought it might be used as anti-Semitic propaganda,” she says. “I could see how it might be misconstrued that way now.”

Director Eleanor Reissa counts herself ambivalent. She’s a woman of many identities, with feminist leading the list. Still, as the daughter of Holocaust survivors, it’s the yellow Star of David that most defines her offstage and as an actor/director. “On the one hand I feel I can say and do anything,” she notes. “I’m entitled to be irreverent and bold. But on the other hand, I’m not entitled to anything and don’t want to offend anyone.”

The Indecent team has also wrestled with the piece’s legacy of perceived anti-Semitism. While they’re sympathetic to the young Asch’s irreverent sensibility, as mature artists themselves, they see both sides of this complicated issue, and have been careful to mitigate any elements that might smack of stereotype.

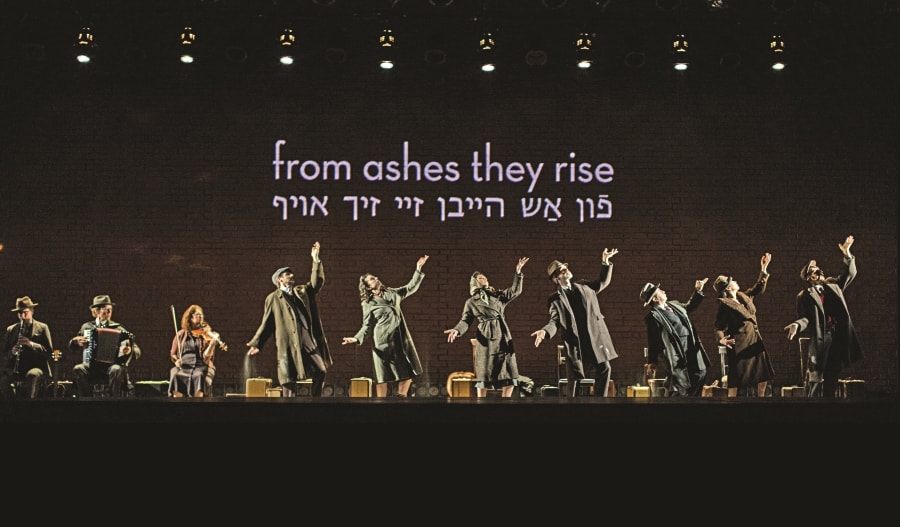

Following a troupe of actors who perform God through the years, with a nod to the actual trial, Indecent makes reference to the pogroms and even the Holocaust as a way of placing the characters in the play and the public’s mixed response to it in a global context. Indeed, Indecent attempts to tell a larger story, merging issues of immigration and censorship with Yiddish theatre history and Jewish assimilation, and speaking to its intersectional nexus: “otherness.” Marrying dance, movement, music, and a hint of Our Town (there’s a genial stage manager, Lemml), the stylistically hybrid Indecent is a lyrical, campy, even farcical play-within-a-play.

“Our biggest challenge,” Taichman says, “was to give the audience enough of the original play to understand and care about it as a story without taking up too much real estate.”

Indecent might never have happened if not for a bizarre confluence of events, starting with Taichman discovering God as a graduate student at Yale Drama School when she was looking for a piece that would serve as a springboard for her 16-minute masters thesis production. Like Vogel, she was floored by the work and fascinated by the story around it, including the obscenity trial. Coincidentally, the trial’s transcript was also housed in Yale’s library. Taichman interwove the two texts to create her thesis piece.

As her national directing career grew, Taichman remained haunted by God of Vengeance. She wanted another shot at it. When a friend suggested Taichman contact Vogel about it, she was reluctant. “It felt audacious,” she recalled. “But when I finally got her on the phone and started talking, Paula said yes within 10 minutes.”

Unlike the Indecent team, New Yiddish Rep’s God director Reissa didn’t have the mixed blessing of creating a brand new piece. She had only the original text to work with. In a bow to modern audiences’ changed attention span, she made some cuts, though she was careful not to destroy the play’s rhythms or the authenticity of its language. But in an effort to make God universal—and arguably less anti-Semitic—she has set the play in a timeless, non-specific netherworld, focusing her metaphorical spotlight on Asch’s themes of class, the sins of the father, and the limited choices that poor women face in all ages and places.

Many Jewish women survived as prostitutes at the time Asch wrote the play, though in some instances they were freer and less demeaned than the wives of brutish men, as Asch makes clear in his play. Reissa concurs, even as she recognizes the danger of sentimentalizing their plight by suggesting they were somehow happily liberated.

And then there’s the lesbianism. Though as written the relationship between Rivke and Manke is unequivocally a love story, by most accounts it was coarsened and made grotesque on Broadway in 1923.

“In that production Manke was seducing Rivke as a way of introducing her to a world of prostitution,” says Vogel. “The idea was that she would sell her and then make money. That was not what Asch had written.”

Indeed, both Indecent and the new revival of God depict the relationship between the two women as sincere and profoundly loving. In fact, it’s the only loving relationship depicted in God of Vengeance. Says Shayna Schmidt, who plays Rivke in New Yiddish Rep’s God, “I don’t even play it for the sexuality.”

Notes Reissa, “What makes it even more interesting is that it never even occurs to Yankl that his daughter has fallen in love with a woman. He’s terrified that she’s hanging out with prostitutes and, God forbid, has been with a man.”

Speaking Yiddish onstage adds yet another hurdle, not just for New Yiddish Rep’s production cast but also for some of the actors in Indecent, who render a few well-chosen scenes from the play in full Yiddish. None of the actors in Indecent knew the language, so a coach was brought in to help. Curiously enough, hearing and speaking the language turned out to be an unexpectedly powerful experience for all the actors and creative team, “especially in the context of a piece that looks at the near death of that language,” says Taichman. “Also, we felt it brought us closer to the experience of the play God of Vengeance as it was originally written.”

Taichman continues, “My grandfather was a Yiddish poet, and Yiddish was always floating around our house. I always felt connected to the sounds and the feel of Yiddish. Hearing Yiddish brings back the sounds of my ancestors. In Indecent we attempt to make a kind of Kaddish for the Yiddish language,” she says, referring to a ritual prayer of mourning. “I’m not sure there has ever been a collective and public mourning for this largely lost language. It is important also to say that the language lives still, though at a small fraction of what it was, and that there is a great effort to keep it alive.”

New Yiddish Rep is undoubtedly at the head of that effort. But not all the actors in the new production of God are native speakers, and their dialects vary depending on where and how they learned the language. Riessa has attempted, though, to incorporate these inconsistencies into the performance, as the characters do come from different places, with varied educational and economic backgrounds, all of which would have been reflected in their Yiddish.

Both O’Brien and Baker, for instance, mastered the language with the help of accomplished Yiddish actors, and thus speak a standard stage Yiddish. The ex-Hasids, meanwhile, talk with distinctly Borough Park rhythms, cadences, and pronunciations. Their rapid-fire delivery does not lend itself to the kind of clearly delineated enunciation necessary in a performance, they acknowledge.

There’s another disconnect, the young ex-Hasids say: Speaking and acting an often profane story in a language they associate with their strict religious upbringing. “It’s as if what I’m saying violates the way I’m saying it, speaking Yiddish,” says Twersky.

The dissonance goes beyond language, Rosen says. “There’s a lot to overcome onstage,” he says. “In the Hasidic community there’s a strictly defined range of movement and expression. There are narrow, preconceived responses for every occasion: You cry because you’re mandated to cry. You’re happy because you’re mandated to be happy. You walk as if you are heavily burdened. Your head and your eyes are cast down. It’s part of the culture and religion.”

Melissa Weisz, who plays the prostitute Manke, grew up Satmar, the most austere Hasidic sect. She says she always struggled with the community’s expectations, with the inequity between men and women, and with the unquestioned religious beliefs; she left that world following the dissolution of an arranged marriage. Weisz knows from personal experience what it’s like being marginalized, and sees Manke’s evolution as analogous to her own: Manke, the ultimate outsider, demonstrates great strength and personal resolve. She has made a difficult choice.

“I know something about what’s entailed in making a choice and the cost of freedom,” Weisz says. “And because I’m now far enough removed from the Yiddish of my youth and the community I came from, I can see the beauty, poetry, and sexuality in the language. It’s a whole new context.”

For O’Brien, who played Hindl in her own 2001 English translation of God, going back to the original language makes all the difference in the world.

“My voice is now emerging from a different part of my body,” she says. “It could be age and maturity, but it’s also the Yiddish that’s making my voice feel more grounded and my character stronger, more intelligent and feminist. She’s not the same Hindl I played in English.”

She and Baker, the two Gentiles in the cast, are especially committed to getting it right. For her part, O’Brien was introduced to Jewish literature by the nuns in parochial school, and has always felt a strong kinship between Gaelic and Yiddish, two endangered languages of the people. Baker, who attended a strict Lutheran school in Kansas City, sees a bit of his own upbringing reflected in God of Vengeance. His father, he says, “could not imagine a child not fulfilling his own expectations; I’m gay. My father was not unlike Yankl.”

Still, as a non-Jew, Baker says he has been especially careful to avoid underscoring his character’s unattractive traits, and in all his years staging Yiddish theatre he’s personally avoided roles with any hint of stereotype.

“Yankl’s religion is not a real Judaism, but a superstitious fetish to protect his daughter,” Baker reasons. “He’s not a stereotype. The rabbi/matchmaker is a great role too, but I wouldn’t come near him. The ADL would be all over me.”

Asked what he’d like audiences to feel after seeing the play, he sums up the company’s collective thoughts.

“I want them to be devastated and think about how they relate to their children, how they relate to everyone and how we all use each other—including God, with whom we’re constantly bargaining—to carry out our personal agendas. That’s eternal.”

Vogel likewise hopes that both Indecent and God “make audiences appreciate what theatre can give us in a time of censorship and cultural divide. But most of all I want Indecent to be a product placement for God of Vengeance. It’s a great play.”

Asch’s great-grandson, David Mazower, who spoke to me from London, echoes the sentiment. He is profoundly gratified at the two upcoming productions. He has already seen Indecent, a play he admires enormously, describing it as “bold, ambitious, and theatrical.”

A news journalist with the BBC and a writer on Yiddish culture, Mazower is looking forward to returning to New York with his two daughters to see the New Yiddish Rep’s God of Vengeance, a play that continues to have great personal resonance for him, especially in its depiction of a father/daughter relationship. His maternal grandmother, whom he remembers vividly, was Asch’s only daughter, and their intense bond is reflected in the play.

“Asch would have been pleased and flattered at the interest in his play now, but not really surprised,” Mazower says. “He was not a retiring, modest man. At the same time he would have had mixed feelings. He wrote God of Vengeance when he was 26 years old, and it was the reason for his early meteoric rise. But, like a parent with more than one child, he didn’t want it to overshadow his others. He wrote more than 20 plays; four or five were long-running.”

Mazower speculates—certainly hopes—that the current interest in God will lead to translations of Asch’s other works, including short stories “that have the broad, multifaceted dynamics of modern dramatic literature,” he said. “It’s long overdue.”

New York City-based writer Simi Horwitz is the recipient of a variety of honors, including two prizes from the Los Angeles Press Club’s National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards.