This holiday season finds me contemplating legacy, and how we share what we know across the multiple generations of our field.

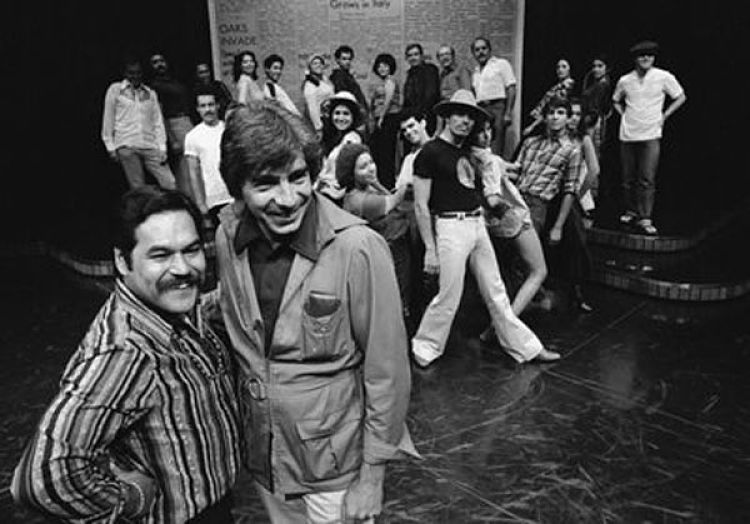

The notion of legacy is particularly poignant this year, as we’ve lost some of our movement’s first- and second-generation founders and brightest lights: Martha Coigney, Zelda Fichandler, Gordon Davidson, Jim Houghton. At TCG’s National Conference in June, we honored living legends John O’Neal, founder of the Free Southern Theater, and Michael Kahn of the Shakespeare Theatre Company, while simultaneously welcoming teen councils from Berkeley Repertory Theatre, Milwaukee Repertory Theater, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, the Alliance Theatre, and Center Theatre Group. There was a touching moment during the conference’s opening plenary in which Anna Deavere Smith shared a remembrance of traveling with Mr. O’Neal when she was a young artist and how that experience changed her. Our Legacy Leaders of Color Video Project, created over the past couple of years, is intended to ensure that future leaders will not lose the stories of how some of our theatres of color were founded in the 1960s and ’70s. The project features Luis Valdez and Miriam Colón, two inimitable artists who are covered in this issue.

There’s a potent, palpable generosity of spirit when we come together in these contexts and recognize our interconnectedness and interdependence—sharing ideas and expertise; passing along stories of how it all came about, what’s worked, what has departed from the founding visions, and why; balancing what mattered to past generations with the vision of new generations; and collectively defining what a vibrant, healthy field looks like in this time of shifting landscapes, political and economic uncertainty, and philanthropic support that is ever-changing and unpredictable.

TCG exists in part to make this knowledge- and expertise-sharing possible, across the broad landscape of America’s professional theatres and the practitioners who energize them. The process, which in the early years of the movement happened simply among peers, has evolved over the decades in both formal and organic ways, and we see things now with a clarity that only time and experience can provide.

On a recent trip to Seoul for the Korean Arts Management Service Performing Arts Market, I visited with professor Miy He Kim, who is working to transmit some of the stories of the American resident theatre movement to a South Korean audience. I first met her when she came to the U.S. to write a book about theatre, and I learned of her hopes to inspire young Korean theatremakers to look beyond the big city to other regions where their work may be needed and embraced.

Seoul, I can testify, is the locus of a healthy contemporary arts scene, with up-to-date accomplishments in theatre, dance, music, and visual art. I was also exposed to some of Korea’s rich traditional forms, kept alive by master artists and performance companies who have been designated by the Korean government as “National Intangible Cultural Assets.” These master performers pass down their forms to younger artists, and in some cases have elaborate transmission systems to make sure that happens effectively. For example, the dance/music form Gangneung Nongak (which is designated as National Important Intangible Asset No. 11-4) is being handed down throughout the Yeondong region of Gangwon-do, via a master artist, an “artistic talents holder,” five transmission teaching assistants, and 60 performers who are part of the Gangneung Nongak Preservation Society. Also working to preserve the tradition and its special techniques are seven village performance groups, three primary schools, and one middle school.

This carefully crafted effort got me thinking about our own theatre ecology and how it is managed by the artists, administrators, trustees, students, and teachers who interact within our vast national theatre system. Collectively, we are an intangible cultural asset of our own country, aligned with such positive forces as creative expression, education, human connection, and beauty. But we also represent something more tangible: jobs. Our movement is a foundation for artistic careers in cities and towns throughout the nation. We transmit what we know about making the art and running the institutions through our convenings, through our communications, through one-on-one mentorship, through school partnerships, and through the performances themselves.

As we think about the new year ahead—and about how the world may be different with a new administration in Washington—this is also a chance for us to contemplate the ways in which we come together to share what we know. Are our college and graduate theatre students aware of the legacy we have inherited as well as the present realities of the field? How can we mentor others, and, especially, mentor those outside of our existing networks? How can late-career leaders provide guidance to those who are just starting out and may have differing priorities?

There are wonderful potential answers to these questions in this issue. It was Luis Valdez who charged the Latina/o Theatre Commons to think of themselves as being an integral part of a new American theatre. It was Rosalba Rolón who, in a merger with the Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre, kept alive the vision and culture of her company Pregones, rather than having it subsumed into the existing vision. It is LORT theatres such as the Goodman and Dallas Theater Center that are collaborating with Latinx theatres for new productions and play festivals. The interdependence and information-sharing of our field becomes ever more robust. The new American theatre toward which we are headed weaves us all together.