DENVER: The Latinx community in Colorado’s capital city is vibrant. The Chicano Humanities and Arts Council art gallery, the Museo de las Americas, and theatre company Su Teatro are all along Santa Fe Drive in the city’s Lincoln Park neighborhood. The city is also home to the nation’s largest Cinco de Mayo celebration, complete with live music, parades, and a taco-eating contest in May. Community members honor the memory of loved ones by creating altar displays, crafting sugar skulls, and marching in candlelit processionals in celebration of Día de los Muertos each November. And year-round, Su Teatro develops and presents full-length productions honoring the rich history of the Latinx community in Denver. American Theatre caught up with artistic director Tony Garcia via email to learn more about the theatre’s 40-year history.

Who founded Su Teatro, when, and why?

Su Teatro was formed in 1972 from a class taught by Rowena Rivera at the University of Colorado at Denver (UCD). Rivera was asked to teach a remedial reading class because the university believed the incoming classes of Chicano students could not compete at the college level in basics such as math and literacy. She found it insulting and proposed that she teach a teatro class using the “Actos” book by Luis Valdez. The students also wrote, staged, and directed original work. Those students formed Su Teatro, and they have gone on to be successful teachers, business people, and artists.

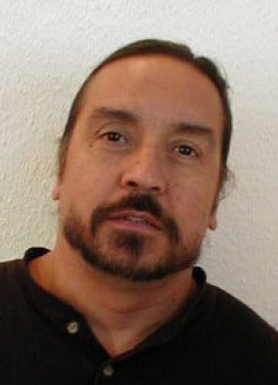

Tell us about yourself and your connection to Su Teatro.

I saw Su Teatro perform when I was 19, and I was entering college late because I had dropped out of high school. After a semester at Community College of Denver, I was able to transfer to UCD. I saw Su Teatro perform in the spring of 1972 and I was blown away by their performances. I was a musician (guitar) and I played with a guy who was really good. The members of the theatre had seen him perform and really liked him. They urged him to join, and I came with the deal. I was going to school because I was going to be a writer—I actually started as a journalism student—but I quickly switched to theatre and began writing plays for the group. They were small at first, but as the group developed, we began to perform full-length work, usually with music.

I became the artistic director early on. Later, when we moved into our first facility, I took on the role of executive director.

What sets your theatre apart from others in your region?

Su Teatro is a hub throughout the region. We have been producing work for so long and have been very involved in contributing to the canon of Latino theatre. We have developed and produced more than 40 pieces which we have toured and presented multiple times in our space. Our community travels to Wyoming and Nebraska in the north, New Mexico in the south, and Utah and Kansas to see the work that we are presenting. It is not unusual for people to plan anniversaries and family visits around our schedule to see the performances.

Who is your audience?

Our core audience is Mexican-American or Chicano. They are 25-65, mostly female, and college-educated. But that doesn’t mean that is all there is. Su Teatro has a very working-class audience and also a solid audience from the dominant culture, a.k.a. white people. People come because of the universality of our work. Latinos are an increasing segment of the population, and because so much of our story has not been told, there is a large space for people to connect.

Tell us about your favorite theatre institution other than your own, and why you admire it.

We kneel at the feet Luis Valdez and El Teatro Campesino. They were the first, and Luis is the father of our theatre movement. Their next generation is still killing it, as the recent production of the Popul Vu indicates. I also love Pregones Theater and Gala Theatre on the East Coast, the Latino Theater Company in the west, and Borderlands Theater and Cara Mía Theatre in the middle.

How do you pick the plays you put on your stage?

Our aesthetic is to express the Chicano/Latino experience onstage. We are interested in work that features Latinos as the driving force in the play. We proudly call ourselves a “community theatre,” and what we mean by that is that we seek active engagement in our community—which is the reason we develop a lot of our own work. We have written and developed a body of work that has presented the history of Mexican-Americans in Colorado. From the Ludlow massacre (in Southern Colorado) to the displacement of the Westside barrio (a neighborhood in Denver) to the story of six Chicano activists killed in a bombing in Boulder in 1972, these are stories that we could not pick out of a catalog of plays. They need to be created from our community.

With that said, our season can also include work by a variety of artists, including Octavio Solis, Luis Valdez, Culture Clash, Cherríe Moraga, Milta Ortiz,Marisela Treviño Orta, Rose Portillo, and Theresa Chavez. We look for work with music that does not come from the American musical tradition; we see it as part of a new American tradition. We do four shows a year and we have to fill a lot of seats. We program at least one of the shows to crossover into high school and middle school, and we program a holiday show.

What’s your annual budget, and how many artists do you employ each season? We are at about $650,000, which goes a lot further in Denver than in L.A. or New York City. Although we do not employ any full-time artists, everyone does get paid. As with many art groups in the nonprofit sector, we wear many hats. In addition to being paid for performing, our artists also work as teachers and administrators, bar managers, and even executive directors. We have six full-time staff members and five part-time employees. We cast about 40-50 actors per season.

What show are you working on now? Anything else in your season that you’re especially looking forward to?

We are preparing to produce MAS by Milta Ortiz, which is the story of the fight to save Mexican-American studies and addresses the Tucson Unified School District’s decision to end Mexican-American studies programs and the community’s battle to hold onto their history, identity, and humanity. The play encapsulates how so much of what we do is provide a vehicle to help our community continue to tell our stories and our history.

Strangest or funniest thing you’ve ever seen (or put) on your stage?

In the early days, we would set up and perform in the parks. We would arrive unannounced and rouse everyone from what they were doing and invite them to the performances. Planning was not our forte. We would probably describe them as “spontaneous” today, but really the term “unprepared” is a better descriptor. One day we showed up, and while the others set up the curtain across a couple of trees, I ran through the park. I was 21, very skinny, and enthusiastic as I approached a group of older vatos (men) who were polishing their fine cars, drinking their beer, and showing off their much more muscular arms than mine. I told them excitedly about the show we were going to be doing and what a great benefit it was going to be to our community. They said little but acknowledged me with a glare that meant I should get lost.

We finally set up for the show and people actually gathered. Somewhere in the middle, it started to get dark and then really dark. Of course, we had no lighting; that would have meant resources and forethought. Yet the families that had gathered stayed. Just as it reached the point where we could not see, we saw a collection of neatly polished and slicked-out cars driving on the grass and forming a semi-circle of headlights around us. We finished the show well-lit. After, I approached the guys, wanting to thank them in my nerdy post-performance exhilaration. Once again they glared and told me it was time to move on. Sometimes it is best to leave well enough alone.

What are you doing when you’re not doing theatre?

After 42 years everything still revolves around the theatre. My daughter and grandson are both very involved in the theatre, therefore there is a lot of family connection. I like to work around my house, which I seldom get to see. I cook and then I like to spend as much time at the gym as I can, because as old as I feel while I am working out, I feel so much younger when I am done. There is a meditation element that comes with physical exercise that really energizes the creative part of myself.

What does theatre—not just your theatre, but the American or world theatre—look like in, say, 20 years?

Technology has always been a great force for democracy. It has been a great balancer of economics and politics as access has improved in marginalized communities. So I would think that people utilizing the simplification of technology will make for more sophisticated storytelling. It will also allow for more long-distance interactions. In the end, if we are smart, it will serve as a means of bringing us all together in the same room to share what is fundamental to theatre—and that is the communal and ritualistic element.