When I speak about it with people who saw it, the phrase that comes up most often is, “It was life-changing.”

When I speak about it with people who have read about it, but didn’t see it, the question that inevitably arises is, “What was the coup de théâtre?”

When I speak about it with people who knew nothing of it, they profess surprise that it existed.

I’m speaking of the Hartford Stage production of March of the Falsettos & Falsettoland, the first time the two shows were produced as a single evening. Directed and choreographed by the marvelous Graciela Daniele, the shows were playing exactly 25 years ago as I write this, in a 41-performance run in Hartford Stage’s 489-seat theatre in October and early November of 1991. At most, 20,049 people saw the production; it was at least a few hundred less than that, because, to the best of my recollection, the previews weren’t sold out.

I was the theatre’s public relations director at the time, and it was one of the more ecstatic times in my career. From the moment artistic director Mark Lamos informed us we would be doing the show, I was thrilled. Though I did not see the original March of the Falsettos in 1981, I played the vinyl cast recording (owned by one of my college roommates in those pre-digital days) incessantly in my junior year, almost as a nightly ritual. When Falsettoland debuted at Playwrights Horizons in 1990, I made sure not to miss it.

I have to credit Bill Finn and James Lapine’s musicals with helping to form my perception of gay life. I was a straight, cisgender kid from a Connecticut suburb in an era and area when one didn’t encounter adults who were out, let alone high school students. I don’t remember any particular fear of or enmity toward gay students on my part (I hope my memory is correct), but I also don’t ever remember the topic coming up until I got to college.

The humor and sincerity of March, from the opening of “Four Jews in a Room Bitching” to the simple closing of “Father to Son,” left me wanting to march along with Marvin and Whizzer and Jason (and Mendel and Trina and Cordelia and Dr. Charlotte), because love, as far as I was concerned, was love. I sang that message over and over in my off-campus room, embedding it in my everyday life as I came to know and love gay men and lesbians as my world expanded through theatre. (I should probably give a small shout out as well to The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which broke down barriers around sexuality and gender fluidity for straight suburban kids as much as anything else we encountered in the late ’70s.)

It may be difficult to understand today, but producing a musical about a man who leaves his wife for another man yet attempts to retain family ties was still an edgy step outside of a major city in 1991. The politics of “outing,” naming someone as gay in the media even when they had not declared themselves to be so, was hotly debated. Gay/straight alliances hadn’t really reached northern Connecticut, just 120 miles from New York City, though AIDS certainly had: My first landlord in Hartford died from it in the late ’80s.

To market the show, the direction I was given was not to confront the subject matter directly, but only to entice people enough to want to see it and allow the story to reach them once they were in the door. It didn’t hurt that at the time, subscription tickets filled some 75 percent of the total seating capacity for the run. A lot of people were coming no matter what I did.

Because we had begun using marketing taglines, aping film advertising, I cobbled together something to the effect of, “It’s about parents, children, love, sex, baseball, and bar mitzvahs.” Our graphic imagery in ads was utterly abstract, saying nothing overt at all. Because this was in many ways an experiment, the show’s title remained the unwieldy March of the Falsettos & Falsettoland; the condensed title, Falsettos, would come later.

I knew something special was going on when I would visit the rehearsal hall, whether to track down an actor for a program bio or to accompany a journalist who was doing an interview during a lunch break or at the end of the day. What struck me most was that whoever was in the room during a rehearsal was, as far as Graciela Daniele was concerned, part of the rehearsal. I remember her calling out questions to me as I sat on the sidelines; curious about bar mitzvahs, she became the only person to ever listen to the audio recording of my own bar mitzvah (including me). There were no barriers in Grazie’s space, only inclusion.

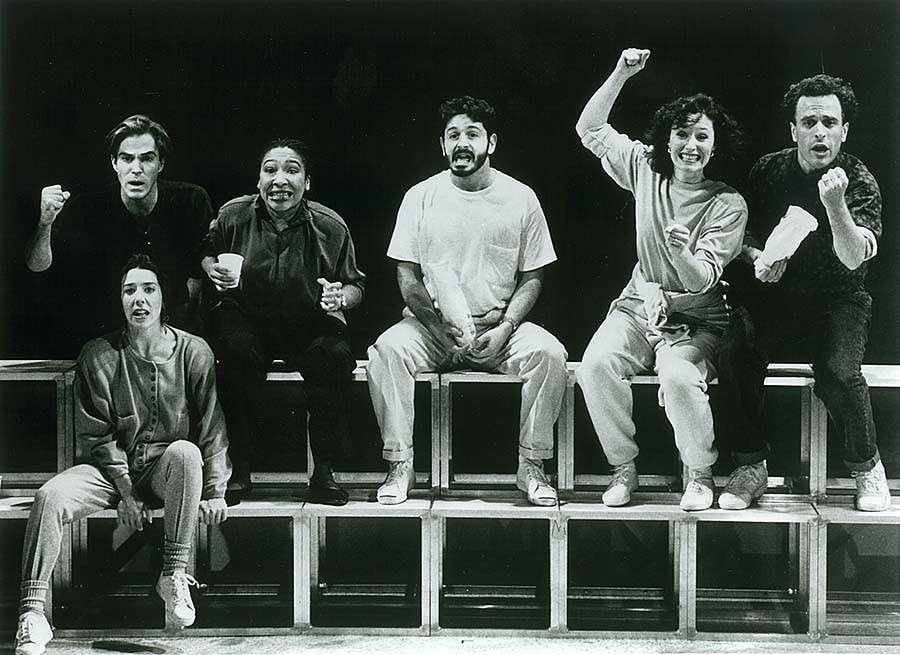

Once the show was in the theatre, audiences responded very favorably, with cheering and weeping. If there were letters of complaint over the subject matter, I either never knew of them or have long forgotten them. One staff member, while out to his friends and coworkers, was so moved after seeing a preview that he promptly came out to his family, as he proudly told us all. On matinee days, many of us would slip into the theatre at certain times for particularly memorable moments: We were often there together as Barbara Walsh, as Trina, nailed “I’m Breaking Down” in March; we were there for the final moments of Falsettoland, perpetually moved as Adam Heller, as Mendel, sang, “Lovers come and lovers go/Lovers live and die fortissimo/This is where we take a stand.” We endlessly laughed over the anecdote told by Evan Pappas and Roger Bart (who played Marvin and Whizzer, respectively) of a student matinee in which, when the lights came up on the pair in bed, one student announced rather loudly, “Ooh, they’re gonna get some.”

The whole experience became heightened when Frank Rich, then the chief theatre critic of The New York Times, rendered his verdict.

It was a secret, until now, that the two “Falsetto” shows, fused together on a single bill, form a whole that is not only larger than the sum of its parts but is also more powerful than any other American musical of its day.

For this discovery, audiences owe a huge thanks to the Hartford Stage. Under the artistic direction of Mark Lamos, it has the guts to produce these thorny musicals together at a time when few nonprofit theaters are willing to risk aggravating dwindling recession audiences by offering works that put homosexual passions (among many other passions in the “Falsetto” musicals’ case) at center stage.

With unstinting praise, he went on to note:

She [Daniele] has brought off an inspired, beautifully cast double bill that is true to its gay and Jewish characters—and to the spirit of the original James Lapine productions—even as it presents the evening’s densely interwoven familial and romantic relationships through perspectives that perhaps only a woman and a choreographer could provide.

Of course, the box office exploded, selling out the remainder of the run within a day. House seats, which I instituted as a practice a Hartford Stage for the first time when I came to the theatre and were only rarely needed, were in high demand. And the talk began of Broadway.

That talk continued for several months, but without going into what were protracted and emotionally trying times, the Hartford production, as we all know, did not go to Broadway. It was Lapine’s original that returned to New York, with the core original cast members (except for Barbara Walsh, our Trina, who joined the Broadway production). As a result, the Hartford Falsettos became the stuff of legend, though regional theatre legends tend to fade with time. But over lunch with Evan Pappas a few weeks ago, our first in quite some time, he noted that 25 years on, he still meets people who saw the show in Hartford and tell him stories about how it changed their lives.

I suspect productions of March, Falsettoland, and Falsettos have been changing lives for a very long time, whether directed by Lapine, Daniele, or any of the many other directors who have brought that story to the stage. I was privileged to have seen Grazie’s production as often as I wished; I’ve seen the previous Lapine productions several times and will see the new one in a couple of weeks.

I couldn’t be happier that it’s back on Broadway, though the show will always echo in my head with Grazie’s vision, with Evan, Barbara, Adam, Roger, Joanne Baum, Andrea Frierson, and the twins who shared the role of Jason, Etan and Josh Ofrane. I only wish that Fun Home were still running, because how marvelous it would have been to have two stories on Broadway about family life, love, and pain, set in roughly the same era but written years apart, exploring the thrill of first love and the need for absolute acceptance of gay parents and their children.

Oh, the coup de théâtre? I haven’t forgotten. I saved it for the end, just as Grazie did, though I tipped my hand with the photo at the top of this essay.

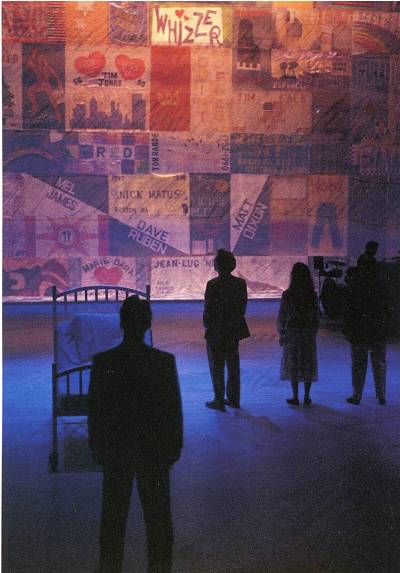

The term comes from Frank Rich’s review. He wrote, “For her finale, Ms. Daniele exploits the spatial dimensions at her disposal with an overwhelming coup de theatre (not to be divulged here) that first reduces an audience to sobs and then raises it to its feet.”

After a quarter century, let me divulge.

Grazie and set designer Ed Wittstein chose to completely open up the vast stage at Hartford to its walls, using no set pieces other than interchangeable cubes—and a bed. The lyrics were scrawled randomly on the entire floor (visible due to the theatre’s arena-like seating), and across the Broadway theatre-sized back wall. To be honest, in shades of black, grey, and white, they largely disappeared, allowing audience members to concentrate wholly on the handful of people singing intimate stories, with no distraction.

But at the very end of the show, as Mendel intoned the final lines, a small square suddenly appeared through the drop that masked the rear wall. On it was simply the name “Whizzer.” Then the drop was revealed to be a scrim as the entire back wall dissolved into a ghostly section of the AIDS quilt. A lever was tripped, rather loudly, and the front drop wafted slowly to the floor, fully and clearly revealing the quilt for just a moment before the lights went out, and the show ended.

While the quilt at Hartford Stage was not part of the real AIDS quilt, it replicated panels from that extraordinary expression of loss that once covered the National Mall in Washington. Because members of the company had been asked if they had family and friends who they had lost and wished to see included, audience members who worked in theatre quickly discovered they knew people on the Hartford quilt facsimile. While much of the audience was in tears, those who saw the names of those they loved and lost were often overcome.

Beautiful, sad, simple, funny, and transcendent. That was the Hartford March of the Falsettos & Falsettoland. I have always understood and accepted that I am spending my life in a world that is forever fading into memory. But if I could ever go back in time to see just one more performance of any show I worked on, it would be March of the Falsettos & Falsettoland. At least it’s still playing in my head 25 years on, and once again, I’m in tears over its beauty as I write, and proud that I had a connection to it. I wish you’d seen it, and if you did, I suspect you know exactly how I feel.