In nearly every show that Harold Prince has directed, there is what he calls “the metaphor,” the central theme or idea on which the story rests. He doesn’t always start the process of a show with this it in mind—in fact, he seldom does—but once he finds it, it becomes his roadmap, leading him through the show’s development and onward to its opening. Prince, who is 88, can still recall with ease the metaphors from musicals he directed decades ago. For instance, Evita: Images misrepresent the true character of a person; Sweeney Todd: A vengeful society grew out of the Industrial Age.

This message discipline, if you will, has created a string of iconic shows and given Prince a bounteous life in the theatre that continues up to today, more than 65 years after he began as an assistant stage manager. Transitioning to producing and later directing, he hit pinnacle after pinnacle—and the occasional valley—in the bargain racking up enough credits and accolades for two separate careers.

Directing was his singular aspiration all along, but he built his credentials by producing such ambitious, profit-making musicals as West Side Story and Fiddler on the Roof, both directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins. In retrospect, Prince acknowledges that luck had a lot to do with his ascent—though he quickly adds that he worked incessantly, indefatigably, and fervently to meet those auspicious circumstances. As a rising director, Prince found an avenue to create musicals that addressed serious, often political subject matter, from Cabaret to Parade; he also showed a flair for old-fashioned showmanship with the still-running megahit Phantom of the Opera.

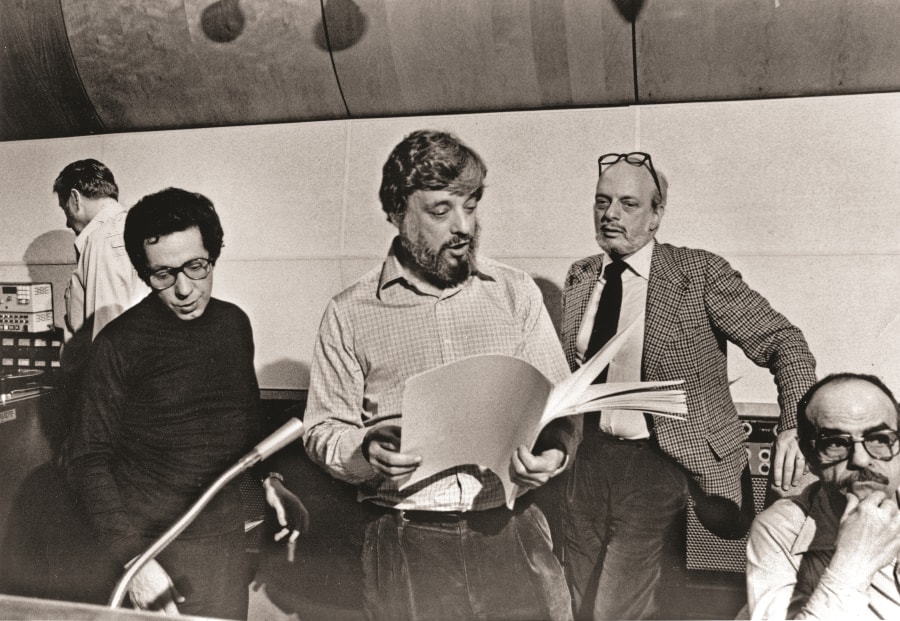

Prince names his relationships with Stephen Sondheim, Andrew Lloyd Webber, and Kander and Ebb as some of the most prized in his life, and his Manhattan office is a celebration of these and other artistic partners. Large and small photographs line the walls, many in black and white, taken in rehearsal rooms and on Broadway stages. There he is with Sheldon Harnick; with Robbins; with Lotte Lenya. His 21 Tony Awards are notably absent, as is his National Medal of Arts and Kennedy Center Honor. (They live at his home.)

At his desk chair, positioned before a wall of theatre books (the only wall not devoted to photos), Prince semi-reclines, glasses perched above his forehead in their signature way, and holds forth about the state of the theatre. The state of producing still matters greatly to him, and he is unyieldingly emphatic that today’s producers must be more creative, daring—artists, not just businesspeople. Not one rest on old successes, Prince prefers to be at work on something new; he happily shares details about the new musical he’s developing with ongoing collaborator Susan Stroman, an amalgam of his hit Broadway shows, aptly named Prince of Broadway.

To be 88 and still love going to work is rare thing in any field. But if Prince were to offer a prescription for a fulfilling professional life, it might be this: Make a path to the work you love, embrace luck wherever you find it, and be on the lookout for the metaphors.

I read that you had a formative experience at the theatre when you first saw On the Town in 1945.

Yeah. I was not fond of musicals. The more dramatic a piece was, the happier I was in the theatre. But On the Town I loved. I thought Bernstein’s ballet music was extraordinary. And what Jerry Robbins did to choreograph to it was extraordinary. And I couldn’t imagine how George Abbott could meld Betty Comden and Adolph Green’s jolly book and this profoundly beautiful material—it was some strange amalgam that worked. I was more than impressed by it. Also, it was an introduction to two great artists, Bernstein and Robbins.

A little more than a decade later, you were producing West Side Story with them. When you look back on that time, do you find yourself amazed at how fast it all happened?

It’s so many years now that have passed and so much career, but I’m always kind of astonished at the way my life has played out. And grateful. There’s a certain amount of luck, no question. And being enormously motivated and ambitious—to a fault, really. I say in the show Prince of Broadway two things that I’ll share with you. One is that I sat at my desk when I was 20 years old in the Abbott office and had one of these things [points to a daily calendar] and I wrote at the top of every day, “Watch it,” as a warning, because I could be hard to take.

Because of your eagerness?

Eagerness and ambition. I did everything at twice the speed. I would come to the office at 8:30 even though it opened at 9. When it closed at 6, I closed the office after everybody left. Some of that was attitude to be observed by other people. But I had to have that life. It’s a wonderful thing to say that in your later years.

The other thing that I say is, “It only takes one qualified person to say to you, ‘You can do this. You can be a director.’” George Abbott was that person. There are a thousand people who tell you that you can’t achieve the life you want. I remember sitting in the Shubert Theatre in Boston as the assistant stage manager of Wonderful Town. Jerome Chodorov brought me pages to type with changes in the show. He said, “I heard that you’re producing a show next year. Well, good luck—it’s gonna be hard!” And I thought, “Luck’s what I need!”

That show was The Pajama Game.

And I was the stage manager. In the ’50s, a producer did not get any percentage of the show. In those days we got $250 a week to run our office. Until the show paid off, you didn’t get a plug nickel. So I paid myself $100 a week as the stage manager.

The show won the Best Musical Tony that year. That must have given you confidence to keep going.

I’ll tell you what it did: It set me on a path. The next year was Damn Yankees. What I had to diagnose with my partner, [co-producer Robert Griffith], was—I didn’t want to be a producer ever, but I thought, [Abbott] doesn’t love producing, why don’t we be his producers? Bobby thought that too. So I took what was available and stayed with it for nine years—but always wanting to direct.

There were so many successful producers; why did the theatre need two new ones? It didn’t, to put it mildly. So what could we do to make ourselves visible instantly, aside from getting a big hit? We figured: We have to pay back this show quicker than anyone pays a show back, and make a profit quicker and bigger. So I promoted all the fabrics from a pajama factory in return for advertising, and I promoted all the sewing machines for the opening set. There was a lot of—what’s the word when you put a Coca-Cola bottle on stage?

Product placement.

Product placement. And it saved us a fortune! We raised $250,000 but we only spent $169,000. We opened in Boston and we were a hit. Knowing we would be a hit in New York even though we had no advance, we decided to send checks for 10 percent of the investment the day before the reviews came out so that when investors opened the paper to see what the reviews were, they would also open their mail and find a check for 10 percent of their investment.

Wow.

And I personally wrote letters to the investors—there were about 175 of them—telling them what was going on. That was unique. We paid off in 12 weeks and it turned a hell of a profit.

How did you know to do all of that on your first production? Was Robert a mentor in that way?

No, I think I was the driving force. He knew everything there was to know about backstage and scenery and how a show looks right, but I think I was the driving force on that. How did I know? When you’re successful in the theatre, as so many producers were, there’s a laziness factor. The intensity with which we developed the first 10 years of our careers was palpable. Meantime I wanted to direct but I couldn’t do it.

From 1954-’61, we had 7 years of success: five musicals, all big hits. Then my partner died on the golf course. I thought, What am I going to do? I counted on him enormously. We were very close. I had just picked up a show called A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and Bobby had gone along with it. Less than a year after he died, it opened. I said to Abbott, “I want to direct a show,” and he said, “You know, your partnership [with Robert] wasn’t going to last.”

So Robert’s passing led to your transition to directing.

Yes, it’s a terrible thing to say. I never had to come to grips with breaking up the partnership, and I wouldn’t want to. I would’ve wanted to direct and we would both produce, but I don’t know how acceptable that would have been to Bobby.

You may not have wanted to be a producer, but it was going well for you.

We had done five hit musicals in as many years, even won a Pulitzer Prize with Fiorello! Everyone thought, Why doesn’t he feel happy producing? Then I hired myself as the director on She Loves Me. No one else would’ve hired me.

When it comes to trusting your own taste as a producer or director, how do you know that an audience will be inspired by what you find inspiring?

You don’t, do you? Are you lucky enough to be born with taste that is acceptable to a large audience? My taste is very specific. A lot of audiences don’t like what I’ve produced and directed, but a lot of audiences do. I’m sort of in the middle there—maybe elitist. The musicals that I want to do reflect what I want the theatre to be.

Can you elaborate?

Yeah, they’re more serious, by and large. The first show I actually directed, She Loves Me, was evidence of someone who had learned the craft and had good taste. I cast it well, it was beautiful to look at. But it wasn’t an expression of where I wanted the theatre to go. I wanted to dig deeper. I’m a politically thinking man. A lot of the material of shows I’ve directed are controversial.

On the Twentieth Century was an outlier.

That was the maverick, and that was because Comden/Green and Cy Coleman had written it and they said, Would you like to do it? I said, There’s one thing that’s unusual: They’ve written an operetta score. It’s a very flamboyant and narcissistic show about larger-than-life, foolish people, so the score was operatic. And I thought, That’s very smart of them. That’s enticing. So I did it. I also had never done a farce. I thought, I don’t know how to do pratfalls and people walking into walls and all that kind of timing that George Abbott was associated with. I learned on the job.

The time periods and subject matter in your shows range enormously.

Yeah, it’s hard to pin down what kind of show I do. But there is a relationship—it’s tenuous—between Company, Follies…obviously Steve Sondheim, but there’s some sort of interpersonal story about neurotic people and nonlinear examinations of character. And marriage.

Are those themes you find yourself returning to?

You bet. And then you get to a show that I had no relationship to: Sweeney Todd. It’s about vengeance. I don’t feel vengeful very much, so in order to direct it, I imposed something on it that no one has done in subsequent productions. I always want to find a metaphor. I thought: This takes place in the Industrial Age and everybody is in a factory, and maybe if we did it in a factory we could spread the vengeance to all the people in the cast, even though Sweeney is specifically seeking revenge for a wife and daughter. Maybe all these people are sharing that vengeance because they’re trapped on an assembly line in a filthy factory, breathing filthy air. I imposed that, and the two writers, Hugh Wheeler and Stephen Sondheim said, “Do we have to write for it?” and I said, “No, you don’t have to write a word.”

So you spread the tension throughout.

Right, and I could say to the cast, “You’re all one character. You are a factory worker, and regardless of your age you’re being murdered by the environment—now go play that.” One actress came to me and said, “I saw a picture of a girl with a paralyzed leg with a cast from her hip to her ankle. Do you mind if I use it?” So she created a character.

Are you receptive to actors shaping their roles?

Very. I love the role of editor and stimulator when you get a creative actor like Angela Lansbury or Len Cariou, John Cullum. They bring you something you don’t expect.

Without Lansbury, Sweeney Todd might have been overwhelmingly grim.

Now, see, that’s a discovery the authors and I made. I had arranged a reading with Angela and Len. There was music in the first act and no music in the second act. The authors and I sat in a room and said, “This is too grim,” and Steve said, “I have to make Lovett funny.” So he wrote “Pies” and “By the Sea” and stuff like that. But she’s vengeful. She has fangs.

What about form? Company is often mentioned as a show that broke the musical form. How does form work with content?

It’s collaborative. Steve called me one day and said, “I have a friend named George Furth who’s written seven plays for a star,” one-act plays. So I read them and said, “If you and George want to come in, we can talk about it.” They wanted Kim Stanley. I said, “The problem isn’t the play—it’s the superstar having to go change makeup and costumes in the wings to play the next character. But there are three plays here that are concerned with one subject and I would submit that there’s a musical in it. Three are about marriage. We could do a musical about this.” We decided to create a bachelor and these married couples, and his awakening to realize that he should get his feet wet. Only Steve Sondheim could write that score. All the songs are written in observing the plays.

How does your directing change, if at all, depending on your collaborators? Going from Sondheim to Kander and Ebb, for example.

My directing style is dictated by whatever the material is.

Did you have a sort of shorthand with Sondheim?

It’s always longhand, really. Steve and I talk endlessly. An interesting thing is, he always writes in pencil, which means he does not commit himself to the end result. I always write in ink because I’d like to think it’s the end result, and of course it isn’t. So I cross out and write over it. Steve just keeps digging. He has a relentlessly probing mind. I admire that so much.

There’s a beautiful quote from him about you two: that he’s a low flame and you’re a high flame, and that after he meets with you, he just wants to write more.

That’s a nice thing to know. I’ve been lucky to work with people who see the theatre as I do. To break ground if you can.

You and Sondheim took a break in the early ’80s and you began to work with Andrew Lloyd Webber.

We had a big flop, and it hurt us. So it seemed we both better work with other people. But we had 10 marvelous years. We separated and did pretty well. There’s nobody better than Sondheim and nobody more stimulating to work with. He pushed me to all sorts of places. But it probably was a good thing that we stretched elsewhere. Evita was a good example of something discovered with another artist.

Was it like finding another part of your brain that you didn’t know existed?

Yeah. That’s a very accurate description. The imagination is infinite. I liken it to this: She Loves Me is the realistic painting you do before you abstract. If you start out abstracting, you don’t know what you’re doing. Every artist goes through that. And so am I still.

A lot of your shows are adaptations: Fiddler on the Roof, Sweeney Todd, Kiss of the Spider-Woman. When you think about source material, how does your approach change depending on whether the original work is a film or book or play?

That’s an interesting and complicated question. Obviously the same thing prevails in adapting a novel or a film: You have to figure out why it’s a musical. I think the single most important thing is to search for the metaphor. You have to find what’s in there that’s unique to you. Ultimately you have to be related to the work you do. Films are very difficult to adapt, because if a film is hugely successful and you’ve got it in your mind, how the hell can you compete with that onstage? Everybody tries. I think I use cinematic techniques: I know how to do a closeup on stage. It’s about lighting. It’s about focus. I know how to do a dissolve onstage from one scene to another. But I don’t think high-tech cinema techniques have any place in the theatre; they distance you from the theatrical experience. What you want to do is make the person in the seat a collaborator. And I believe in minimalism. Everyone thinks I do extravaganza. It’s just not true. In Evita it was justified because the metaphor was how the images you create of a person are divorced from that actual person; you do it with cameras, flash bulbs, and newsreels.

Shifting to your longest-running musical, The Phantom of the Opera, here’s a show that has been unchanged, in its original form…

For almost 30 years.

So it’s both live theatre and historically preserved at the same time. Does it exist in both of those realms for you?

Yes, it does. It lives in both of those realms, because we work on it all the time. I do rehearsals with the company about four times a year. And because you haven’t seen it every week, strange things happen. You say, “This is false.” And it’s all in a Victorian melodrama package. So when you start rehearsing, you say to Michael Crawford, the original Phantom, “I’m gonna push you to almost overact. You have to believe what you’re doing. And trust me, if you go too far, I’ll stop you.” The same applied to Sweeney. Phantom depends on entering a world that is completely unfamiliar. The story we’re telling is perennial: It’s Beauty and the Beast, the Elephant Man. And the anchor of the show is that in the presence of deformity, most human beings recoil—and most are compassionate and intelligent enough to know that they shouldn’t recoil. In the course of the story, you have to take a woman from recoiling to falling in love. And the audience has to think at the end, “I wish she’d stayed with him.” But if she had, nobody would’ve believed it. She has to go with the handsome young man, but she has to yearn for the other man the rest of her life. The audience goes in and they’re like kids opening a Victorian book. They give themselves over to it for a couple of hours.

I’ve read that you don’t have much interest in seeing revivals of your shows.

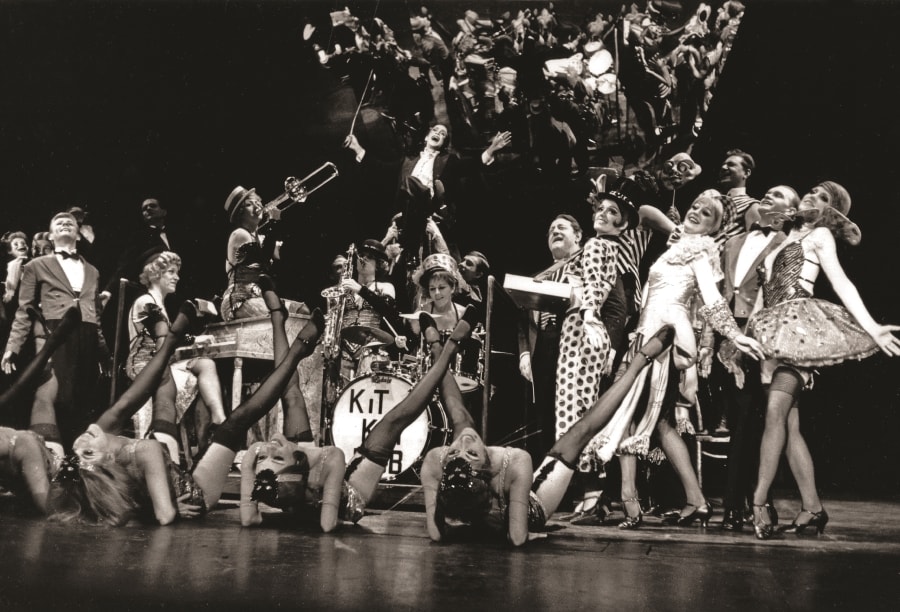

It’s hard. Scott Ellis is a terrific director. He’s done On the Twentieth Century and She Loves Me and he’s done a lovely job. But mostly, no. You put so much into them and the new directors are ignoring the metaphor—the spine of why the show works. And very successfully the metaphors are ignored. For example, the metaphor of Cabaret is that we’re introduced to Germany in the Depression, which has suffered because of its involvement in World War I; then comes the Weimar Republic, and the Emcee is the metaphor. He’s the Depression, and by the end of the first act, he’s beginning to feel power in himself. By the second act, he’s the Nazi and he’s rebuilding Germany. So it’s Adolf Hitler. That trajectory was everything to me. Bob Fosse ignored that trajectory entirely in the movie. And the movie’s very successful! And the version they did at Roundabout is not my play either. It was very successful.

In revivals like those, do you still think of them as part of your legacy because of your work on their original productions?

I don’t know. I don’t feel that people who see them think they’re part of my legacy. In the case of Scott Ellis, he introduced me from the stage. He said, “This is just a revival. The fellow who directed the original is in the audience,” and he had one of the actors bring me up. That was very generous. I don’t owe anything to the revivals of Sweeney Todd. They have no bearing on my factory or what I was doing. That revival didn’t add up for me, but it seemed to add up to audiences, or at least critics.

Is it possible to say you’re both right?

Sure, certainly. If the audience is moved by John Doyle, fine. So, he’s right. But also, I’m right. (Smiles)

You’ve directed two revivals yourself, Show Boat and Candide…

Candide was not a revival; it was a rethink: brand-new book, songs put in different places. And Show Boat was written in 1927; you didn’t do continuous action then. You closed the curtain, played some music, and opened the curtain again. Now continuous action is what we expect when we go to the theatre. In Show Boat, years go by, and what happens in those years affects the lives of this marriage that fell apart. A war, a depression. So I wanted to put the years on stage. I wrote two descriptions of montages, and Susan Stroman staged those montages. So time passed, and what that did was put “Ol’ Man River”—and that’s the metaphor—back into the show. “Ol’ Man River” wasn’t in the second act before. “Ol’ Man River” was time passing.

You and Susan Stroman are collaborating again. What did you think of the world premiere productions of Prince of Broadway in Tokyo and Osaka?

Wonderful. I love that show. We want to do it here. It’s not like any other show. It’s like Cliffs Notes. I’ve picked the numbers, so you get the arc of each show in 15 minutes. In the course of an evening you’ll see an awful lot of shows.

What would you say is the metaphor of that show?

What you see when you walk into the theatre is an empty backstage, and then you fill it with full scenes from other shows. It’s not precisely a metaphor, but it’s a revelation of 21 worlds you can create in the course of an evening. I was backstage at the end of the show and I realized I’m not young. I thought, Holy cow, look what we just did—you just went and looked at your life. Your working life. And I felt scooped out in some strange way. Divested. Too much life.

You know how old I am. My energy level is pretty good. I have hearing aids and I wear glasses to read. But that’s about it. So you have to decide numerically, are you gonna honor it, or keep working until you feel like the shoe dropped? The shoe will drop someday, but it hasn’t yet, so I’m gonna keep working. And doing this show is not a valedictory; I want to do a brand-new show.

You’re making me tear up a little. Is the plan still to bring it to Broadway?

Yeah, next year, 2017. I sure hope so. I’d like people to see it. I’m proud of it. It’s a cast of nine, and the variety of what each actor can accomplish is extraordinary, so each one is my personal star.

Broadway is now fed by shows from the nation’s nonprofit theatres. Have the creative producers of the 1950s and ’60s been replaced by the artistic directors of places like New York Theatre Workshop, the Old Globe, et al.?

It’s a very good question. Sure, but they’re subject to boards. Boards are onerous. I never had a board. But you’re right to say that: The route to Broadway now is through a reputable first-rate regional or New York LORT theatre. And that’s how it has to be because of the cost of everything.

Even back then, shows had out-of-town tryouts to make them Broadway-ready. Is the nonprofit production just a new version of the out-of-town tryout?

It can be. There was work on Hamilton between the Public Theater and Broadway. It would be nice to have the money to do it the way we did it, but by and large you have to go through an association with a theatre. It’s very important to me that Hamilton came along, because I don’t think enough came along in the interim. Audiences have changed. Shows are running a long time—that’s good, I have to like that. But there’s less getting to the stage. Creative teams should be getting more on. It’s not correct to think that it takes 10 years to get a show. We did a show every year, Sondheim and I. Kander and Ebb, every year. Were those shows compromised in quality? I don’t think so; they’re being revived all the time.

Is the difference now that it takes so many years to raise the money?

That’s the difference. My God, it’s taking four years to get Prince of Broadway. It’s reality, but it’s a shame. Mind you, A Chorus Line started at the Public, Candide started at BAM. Do I think there’s as much work being done? No, of course not, if it takes 5-6 years to get a show done.

One positive effect of Hamilton is that it will hopefully give producers more confidence in producing shows that aren’t based on last year’s hit film.

I hope you’re right. Did I want to be a producer who directs his own shows? Sure. But when the costs escalated, I thought, I don’t know how to ask people for money! It was a game when I was a kid. I ran around and got $250,000 in $500 increments. You had a bottle of Scotch and some potato chips. It was fun. There’s nothing fun about asking someone for $10 million. And the person who gives $10 million is not interested in your enthusiasm.

We did West Side Story. The money came, so then we were able to do Pacific Overtures which we knew could never pay its investment back. But [the investors] were happy to be part of the theatre and no one was getting hurt. It’s a different game now.

Last question. Are your awards meaningful to you?

They give them out, I like them. They’re nice to have. But they can’t be meaningful, because there’s work you’ve done where you should’ve been awarded and work you’ve done where it’s luck that you got it. It’s nice where they handing them out to get one. But don’t overestimate what all of that means.