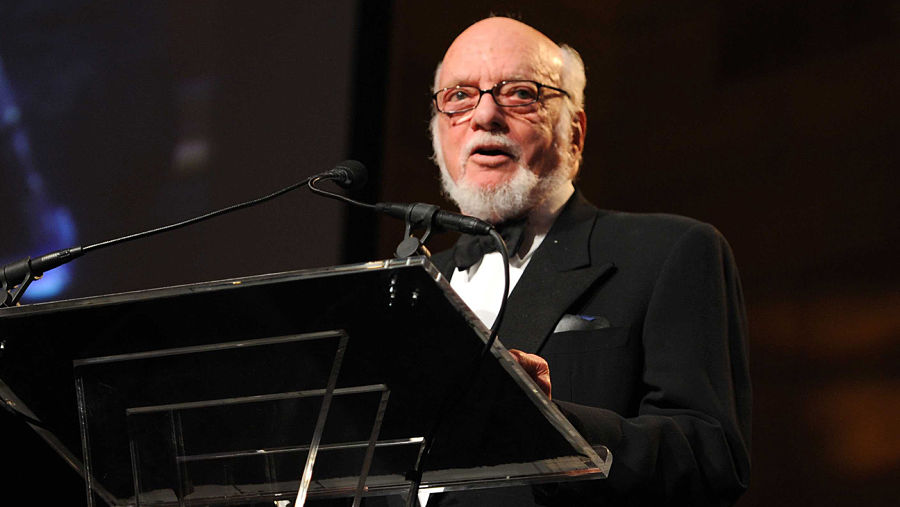

Broadway director and producer Harold Prince delivered this speach to the Broadway Across America convention in Miami last February.

Little-known fact: I was President of the League of New York Theatres in 1964.

I had been impressed into the job by Leland Heyward and Irene Selznick, two of Broadway’s most prestigious producers. I had previously shown little interest in that organization. I imagined it to be an Old Fogeys Establishment. And, to be honest with you, I imagined they considered me a lucky twerp. But Leland and Irene picked me precisely because I was an outlier.

To be truthful, I stayed on only a few years, because I had yet to realize how important collective bargaining was. And had an insatiable hunger to be an artist. I had not yet realized that producers could be creative. Or, more accurately, that they should be. Surely, they may not be writers or designers, actors or directors, but producers should have an artistic sensibility.

But today, the producing population has been infiltrated by investors who assume the job title of “producer.” In the days when I was producing, I had 175 investors. They were press agents, company managers, actors, stagehands, and, of course, a few of my parents’ friends. But the names of producers above the title were never more than three.

If you are a creative producer with an impressive track record, investors should have no serious role reading a script, contributing to the casting of a show, approving its decisions, and—guess what—attending the meeting the day after a show has opened and giving advertising advice.

Look, I certainly know it was easier then. The disproportionate cost of producing today has changed the relationship between producers and potential investors. But I firmly believe that investors should bet on creative teams and let them make the decisions.

Another point: Over the years, surely you know that we have accepted escalating costs and haven’t sufficiently curtailed them. When I started, the cost of mounting a musical averaged $250,000 and a straight play was $100,000.

My career began with the adaption of a book called 7 1/2 Cents, about a strike in a pajama factory in Dubuque, Iowa. We had no experience raising capital. George Abbott agreed to direct it and asked if he could do the first backers’ audition at Howard Cullman’s apartment at 480 Park Avenue. We agreed, and the Cullmans gathered about 100 of the major Broadway investors. When the Cullmans invested, everyone followed. And if they abstained, everyone followed them as well.

Abbott began with these words: “This show is about a strike in a pajama factory.” And you could feel the collective deflation in the room. The composers played selections from the score, including “Hey There,” “Hernando’s Hideaway,” and “Steam Heat.” And at the end of the presentation, we raised zero. Zip. Zilch. Nada.

So, the next day, I thanked Mr. Abbott and took over the chore of raising capital. It was not so much of a chore then, it was actually a hell of a lot of fun. That was then. What followed were 11 auditions in friendly living rooms, passing a bottle of Scotch, some paper cups, and a couple of packages of peanuts and pretzels.

My speech began with me saying, “Our show is Romeo and Juliet in the Middle West. The Middle West is a very popular location these days, thanks to the Broadway hit Picnic,” blah, blah, blah. And in those 11 auditions, my presentation successfully raised our capital.

It took 14 weeks to pay off our first hit musical. Of course, if you had a moderate hit, it would take longer. I know because Company, which I consider something of a watershed project, showed a profit after 21 months and, more often than not, played to 60 percent capacity.

And because you could return the investment on less than full capacity, we were able to produce a new musical every single year. Some of them were blockbusters. A long run in the 1950s and 1960s was 1,000 performances. I needn’t tell you how that has changed today.

And we held on to our original 175 investors through the late ’70s without another presentation. It’s true that Pajama Game is not exactly Hamilton. Nor was Damn Yankees. Of the $250,000 raised for The Pajama Game, we used only $169,000 to open. Damn Yankees, similarly capitalized, spent only $162,000, which accounts for the short payback time. We arrived at this through product placement and having negotiated contracts that were sweetened after the production paid back. We were careful that all of this activity did not compromise quality. And that takes a creative mind—it takes a creative mind to know when to say yes and when to say no. Often, “no” can be as irresponsible as “yes” can be wasteful.

First-rate producing requires taste, as well as the ability to raise capital. But taste is indispensable.

Our next hit was West Side Story, and perhaps that was our Hamilton. True, it didn’t start out as a blockbuster, but, as of now, it has returned 1,521 percent on its original investment.

A little more about West Side Story: I picked it up when Steve Sondheim told me that he, Arthur Laurents, and Lenny Bernstein had lost their producer and there was no—absolutely no—interest from anyone on Broadway in doing a show about gang warfare in Hell’s Kitchen. Though my partner and I were struggling in Boston with a new musical of our own, I jumped at the chance to hear the score and met with West Side Story’s creative team. We flew in from Boston on a free Sunday, came away with the project that no one wanted, and returned to Boston. New Girl in Town, our Boston musical, opened on Broadway three weeks later. It wasn’t good enough, but it returned its investment.

I believe even today there is no dearth of writers—playwrights, composers, and lyricists—or brilliant designers and directors. But stubbornly courageous creative producers…?

Please go back in time and regard the impact of West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Cabaret, Company, Follies, and A Little Night Music. They, too, were subsidized by my 175 investors. I am certain that none of those musicals would have seen the light of day had I not produced them. And, incidentally, every one of these shows came into being without 29-hour readings, workshops, labs, or developmental productions. Can you imagine offering a West Side Story 29-hour reading for investors without its choreography and its orchestra and its brilliant production values?

In 1964, I produced Fiddler on the Roof. Again, there was absolutely no interest from the “Broadway money” in producing that show, despite the presence of Jerome Robbins as its director and choreographer, and authors with elegant track records. But how the hell could I turn that down?

We rehearsed for eight weeks. The production cost escalated to $375,000, and its weekly gross at capacity was $75,383. Things were different, eh? And over the years Fiddler has returned 3,904 percent on its investment.

Now I’ll share with you something I deeply resent: My investors and I took the original gamble of putting unlikely shows on Broadway that ultimately made history. But when those shows have first-class revivals on Broadway, we do not participate in their success. The subsequent revivals of West Side Story, the present Fiddler, the countless revivals of Cabaret, prompt my original investors—and sometimes their heirs—always to ask me what can they expect from these productions. And I have to say: Zero. Zip. Zilch. Nada.

In the ’50s and ’60s, and into the early ’70s, the League was equally divided between producers—the Theatre Guild, the Playwrights Company, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Feuer & Martin, Kermit Bloomgarden, David Merrick, and me, to name just a few—and the theatre owners. And though from the first, it was potentially a weird marriage, over the years the balance has shifted, bringing changes, which are arguably less about artistic growth and more and more about product.

I would be a fool not to acknowledge that we are a business. And businesses provide product. But today, because of theatrical bookings, we are deluged with limited engagement productions, usually revivals, many from the West End, featuring huge stars. The thinking is that they guarantee paying back their investments, but with limited profit potential. And revivals, though important historically, and a stimulus to new work, are not new work. They do not represent the now or the future of the theatre.

In the 1970s, I was a member of NEA National Council of the Arts, and I predicted that there would emerge a successful partnership between the not-for-profit theatres and Broadway. And I was roundly rejected.

But, about the same time, Candide, which I directed for the Chelsea Theatre Center at BAM, was an early beneficiary of this process. Soon to be followed by A Chorus Line. And the list is long, including Sunday in the Park With George, Rent, Avenue Q, and Hamilton.

Now, let me say something—something in praise of our host, Broadway Across America. When I started in the theatre, the road was an ancillary asset. It was regarded as an opportunity to increase our profits by sending out shabby, compromised versions of Broadway productions—dubious casting with unsuitable performers with star names, plus scenery and costumes that were pale copies of the originals.

It wasn’t until Claudia Cassidy, the spiky critic of The Chicago Tribune, assuming the Carrie Nation mantel of the crusader, blasted the hell out of all of us for what we were sending out, that we realized the power of her words as our box office receipts diminished.

Thanks to Broadway Across America, we now observe that the road can sizably increase our profits, that the road is a significant builder of audiences, and that the road is the virus that encourages young wannabe Broadway creators.

In addition, I have observed design teams, having learned from the original Broadway production, actually enhance what they send out on the road.

And surely it is true that theatres across the United States have adjusted their facilities to accommodate every detail of lavish touring productions. I know firsthand that the touring Phantom of the Opera is replicated in all its elegant detail.

So, in closing: For those of you who agree that what the theatre lacks are creative producers, I see a rosy future. To achieve it, we must define what makes our product uniquely different from television and film and build on the living relationship of live audiences and live performances. Inevitably, no two performances are exactly alike, nor is the audience’s response. It’s complicitous, and far more engaging than sitting in a seat in a movie theatre or at your couch at home and “receiving” entertainment.

I would urge you to forget LED walls and holograms and settle on what stage scenery does best: invite imagination.

Choose material and subject matter that surprises and often takes place in surprising locations.

Don’t clone last year’s hit.

Certainly, there will always be products content to entertain, to amuse an audience for two hours of sheer pleasure. But, alternatively, you must honor that audience by engaging them in ideas, in controversy—by inviting them to think.

If there is one point I passionately want to make, not only for you producers, but for your investors—the often 50 people whose names appear above the title of a two-character play— it is this: There are greater profits to be realized in courageous, groundbreaking projects, and a lasting investment, not only in quality, but in financial rewards, when you think in terms of art.

Sergei Diaghilev, one of the greatest producers who ever lived, urged his artists, “Astonish me.”

Well, today more than ever, you must astonish them. And if you do, you’ll save the theatre—both as a product and as an art form.