Feminist playwright-actor Donna Kaz, a.k.a. Aphra Behn of the Guerrilla Girls on Tour, has had a rugged journey, both personally and professionally. Kaz admits she might have been better off had she pursued one of the more traditional professions.

“I would be a lawyer making my case in front of a jury,” she cheerfully asserted over lunch in an Upper East Side restaurant. “Then I would become a judge and finally I would land on the Supreme Court. Go for big!”

Kaz has always gone for big, and thanks at least in part to the efforts of the Guerrilla Girls and later its spinoff the Guerrilla Girls on Tour, the cultural landscape has evolved radically for female theatre artists.

“In many theatres today 40 percent of the plays produced are written by women,” Kaz said. “This past season on Broadway there were two productions whose creative teams were all women, Waitress and Eclipsed. Still, it comes in waves. Two steps forward, one step back.”

Launched in 1985 and conceived as a feminist/agitprop/protest group, the Guerrilla Girls originally advocated for female visual artists. In the late ’80s women theatre artists came aboard, and subsequently branched off in a separate wing that today boasts approximately 20 members who tour the country (often appearing at colleges), lecture, hold workshops, and protest gender inequity in local college or community theatre productions. In an effort to battle stereotypes it stages “Feminists Are Funny” evenings and produces contemporary plays exploring women’s history in theatre and in other fields.

From the outset the Guerrilla Girls were best known for sporting gorilla masks (and sometimes full gorilla suits) and for posting colorful signs in Broadway and Off-Broadway bathrooms. For example: “In this theatre the taking of photographs, the use of recording devices, and the production of plays by women are strictly prohibited—The Management.” A postcard the Guerrilla Girls and their followers sent to culpable producers read: “Dear Theatre Producer, I noticed that last season you did not produce one play written by a woman. I know that you are terribly embarrassed by your lack of familiarity with women playwrights and will rectify this oversight in your next session.” The letter was signed, “Love_____,” with the space left open for the protestors to add their signatures.

Its members assumed the names of dead female theatre artists, from Hallie Flanagan (director of the Federal Theater Project) to Lorraine Hansberry (prominent African-American playwright) to Aphra Behn, the iconic Renaissance playwright Kaz chose as her alter ego.

“When I first became a Guerrilla Girl, it was very cool to wear a mask and be anonymous,” Kaz recalled. “We were very secretive about how many members we had and how we operated. I also thought that if anyone knew who I was I’d be blacklisted in theatre. As it turned out, no one knew and no one cared. Still, we started the conversation,” even at some major nonprofit resident theatres that continue to have “a particularly poor record in producing women’s plays and hiring women directors.”

Kaz still maintains two identities: She insists it’s okay to call her “Donna” once you’ve met her in person, but signs her emails “Aphra,” the moniker she attributes to her activist persona.

Kaz did not start out as a feminist. Her activism evolved following decades-long frustration as an actor/writer (Food, the Musical, Wanderers, and Joan, Interrupted), coupled with an abusive domestic relationship with an actor who went on become a major theatre and film star in late ’70s and mid ’80s.

Kaz did not start out as a feminist. Her activism evolved following decades-long frustration as an actor/writer (Food, the Musical, Wanderers, and Joan, Interrupted), coupled with an abusive domestic relationship with an actor who went on become a major theatre and film star in late ’70s and mid ’80s.

She was young, naïve, and vulnerable then—all the more so as a theatre artist constantly attempting to please the powers that be and getting nowhere for her efforts. She has no doubt that the two strands of her life informed each other.

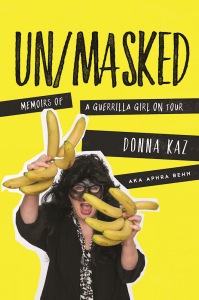

She has now written a readable, provocative, and disturbing account of her journey, Un/masked, Memoir of a Guerrilla Girl on Tour (Skyhorse Publishing), slated to be released Nov. 1. Among other topics, she covers artistry vs. success and how a theatre artist defines herself and persists in a career that’s simply not happening in any conventional sense.

Kaz knows she’s laid herself wide open to the accusation that activism and protest—indeed, the memoir itself—are a smokescreen for disappointment. She continues to have moments of trepidation about the book, but in the end took the risk and feels liberated because of it.

“I saw no advantage to holding it inside anymore,” she said. “I want people to know how hard it is to be an artist, any artist. But it’s that much harder for women artists, especially those living in the shadow of a man. I took a stand against it and have resolved many of the issues that have haunted me. I hope readers might be inspired.”

Writing the memoir took four years for Kaz, who enrolled in the MFA writing program at Queens University of Charlotte, N.C., and landed a residency at Mesa, Calif., for nonfiction authors writing about politics, the environment, or social issues. It was a very painful process, especially “being forced to relive some terrible experiences in order to write the book,” she said.

Finding an agent was yet another trip. Kaz sent out queries to approximately 20 agents, all but one of whom were women. Ironically enough the women either ignored or rejected her. The one man she had contacted signed her, and within short order he tracked down the publisher, Skyhorse. Not all women are in sync with her views, Kaz acknowledges; the Guerrilla Girls got plenty of hate mail from women who felt the group was too feminist on the one hand to those who felt it was not feminist enough.

Clearly the elephant in the room is the actor whose abuse she describes graphically, though she refers to him only as “Bill.”

“I used the name ‘Bill’ because that’s what I called him,” she said. “There were no legal reasons for the decision, though three lawyers went over the manuscript, including one I hired. I also took out liability insurance. I’ve had no contact with Bill in years and I have no idea if he even knows about the book.”

As an artistic youngster growing up in Long Island Kaz always felt like an outsider, a sense of herself that was underscored when she majored in drama at SUNY at Brockport and was sexually exploited by an acting teacher who told her he would advance her career if she slept with him. “At least he didn’t tell me it would make me a better actor,” she said. “I hope that kind of thing is not happening anymore.”

After graduating in the late ’70s she headed to New York’s experimental theatre scene and remembers the camaraderie fondly. But she remembers one well-known artistic director who told her she was talent-free as an actress (he had never seen her act), but because she worked so hard he invited her to serve in a backstage capacity without pay.

Like many actors, she earned her keep working long hours as a waiter. The restaurant was a hangout for many actors, including the charismatic star actor with whom she fell promptly in love. It was a heady time, and within short order they were living together.

When he relocated to Malibu to launch his movie career, she joined him, putting her own aspirations on a back burner. As she tells it their relationship grew increasingly turbulent, marked by his periodic bouts of violence, fueled by alcohol, interspersed with loving interludes only to be topped by more abuse.

“You have to understand I loved him and like many abused women I denied to myself what was happening,” she recalled. “I was economically dependent on him and had no life of my own. I wasn’t an actress. I wasn’t even Donna Kaz. I remember going to a Hollywood party and immediately gravitating towards the wait staff. I wanted to put on an apron and help out. I spent the whole evening with them.”

The transformative moment occurred when Kaz started working for a domestic abuse hot line, though it had no personal resonance for her initially. “The connection was totally unconscious until I got there and saw women identifying themselves as survivors,” she said. “I realized that was my identity.”

Her painful relationship with Bill was a catalyst for her activism on behalf of victims/survivors of domestic abuse and her return to theatre. For the first time her ambitions were front and center. That was the good news. The bad news, she said, were the sexist roadblocks she faced, though she was pumped to take action and ultimately joined forces with the Guerrilla Girls.

“Today demanding 50 percent representation might be off-putting, but back then it was a good way to make people think about the issue,” she said. “We’ve been called the ‘quota queens,’ but that doesn’t mean we want companies to produce plays just because women write them. We’re constantly told that there just aren’t as many women playwrights as male playwrights. That’s not true.

“The problem is that audiences—including women, who are the main theatregoers–have been fed the male narrative for so many years,” she continued. “It’s time for the female narrative to be heard, and I’m not only talking about plays that center on women with babies or women who are the victims of domestic abuse. We want to see plays about women protagonists across economic, ethnic, and racial lines who have real pursuits and go for them. The audiences will come.”

Progress is being made, though, not least in the growing number of organizations and theatre companies dedicated to producing and promoting the work of women, from the League of Professional Theater Women to 20 Percent Theater Company Chicago to the Los Angeles Female Playwrights Initiative to the Kilroys.

Kaz’s immediate goal is to create a three-day summit that would bring together these and other theatre groups, commercial and nonprofit producers, male and female theatre artists, and any and all parties interested in gender parity in theater to be supportive of each other and exchange ideas in a congenial and structured setting where workshops, symposiums, and panels would be offered.

“And the Roundabout would pay for it,” Kaz said, only half-kiddingly, then paused. “There’s going to be a major change when Hillary is elected president. We’ll get backlash, and I’m ready for it. But a woman in the White House will inspire so many women to write their stories and many more people will be open to hearing them. It will be monumental.”

Kaz is currently writing a play and musical about aging women, who are typically invisible or presented as caricatures. She looks forward to changing the conversation on that one too.

It’s been a learning curve for Kaz, who says writing her memoir has been a redefining experience for her, especially on the topic of success.

“I now believe if you work hard at your art and are true to yourself as an artist—in a world where you have to identify yourself as early career, mid-career, or emerging artist—you are a success,” she said. “If you take all your rejection letters, put them in a drawer, and keep creating theatre, whether that’s in Scranton or someone’s basement or your own living room, that’s success, especially if you’ve been doing it for a long time. You’re always going to come up against no. The artist has to define her own success and not be afraid to say it out loud, ‘I’m a success.’

“I take full responsibility for my life and own it, though Bill has to own his part of the story too,” she continued. “If I could turn back the clock I’d make the same choices. I like struggle, I like challenge. It’s given me character.”