School segregation in the United States did not end with Brown vs. the Board of Education. One recent report, for instance, showed that New York City has the third most segregated school system in the nation, behind Dallas and Chicago. Last month another study proved that segregation in NYC schools starts at the pre-K level. Well documented, too, is the vast disparity between support levels for schools with majority black students and those with mostly white students.

But for a problem so well known, it’s strikingly rare to hear about it directly from the people most affected by it: students. That’s something that the high schoolers of Epic NEXT, an arts leadership program for youth run by the off-Broadway Epic Theatre Ensemble, have been tasked with changing.

“How do we live in one of the most diverse cities in the world, and we have a segregated school system?” asks Jeremiah Green, a NEXT ensemble member and senior at Chelsea Career and Technical Education High School. “That is mind-boggling.” Chelsea CTE, in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, has a student body that is 56.8 percent Latino and 26.7 percent black; of its 435 students, just 16 are white. “We don’t even have an auditorium,” says Jeremiah. “We have a ‘gymatorium’—a gym/auditorium. There’s an arch, so you can’t even play ball; you’d hit the ceiling every time you tried to shoot the ball.”

Randy Figueroa, a fellow company member, spells it out plainly: “Segregation is still happening, even though the law says it shouldn’t.” Figueroa is a senior at Urban Assembly School for the Performing Arts in Harlem, where 53.4 percent of the student body is black and 42.6 percent is Latino (the school’s 350 attendees include a grand total of two white students).

Green and Figueroa are two of the five students who currently make up Epic NEXT, the top-tier educational offering from Epic Theatre Ensemble. To get into NEXT, students go through a rigorous application process, akin to a college application, after progressing through Epic’s other educational programs, which range from compulsory in-class workshops to after-school programs.

But for these students, the rewards justify the rigor. In addition to advanced acting, improv, and directing courses run by Epic, students get connected with established adult mentors pulled from Epic’s professional productions, with the bulk of the training taking place over a six-week summer intensive. This past summer, mentors included the playwrights Nilaja Sun and Mfoniso Udofia, both of whom have also had professional productions of their own plays produced by Epic.

“The goal of Epic NEXT is to create generative artists and leaders,” says Epic cofounder Ron Russell, who oversees NEXT with Wallert. The program, created through a leadership grant from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, begins with a weeklong residency at Muhlenberg College, where students learn from college-level theatre instructors. (Speaking of college, one telling fact: NEXT, now in its third year, has a 100 percent college attendance rate among its alumni, well above the average in the students’ high schools.) Russell and Wallert support and instruct the ensemble, though the students ultimately write their own material.

There’s one other thing about Epic NEXT that is perhaps even more unexpected: The students are paid. Once a student is accepted into the ensemble, classes are free, and when students are commissioned to create a piece, they get paid for their performances and all their travel and other expenses are covered. For the students, all of whom come from families living below the poverty line, the money isn’t just a bonus; it facilitates the work by allowing them to choose making theatre over a summer or after-school job. It gives them an outlet for their voices, but not strictly on their own time.

Their voices are at the heart of Laundry City, a devised piece the students created as part of a co-commission from Teachers College at Columbia University and the nonprofit organization New York Appleseed, which advocates for equal allocation of education resources in New York City. Appropriately, the two organizations enlisted NEXT to create a play that explores segregation in schools.

For the students, the first challenge was coming to terms with a problem that, while close to home, many of them had never actively noticed. “Growing up, I never really saw it,” says Olivia Dunbar, a NEXT member and junior at Chelsea CTE. “Now that I’m doing this play, I am seeing it. It’s really opened my eyes.” Figueroa compares his own revelation to The Matrix: “I took the blue pill and everything was revealed to me.” Davion Osborne, a junior at Chelsea CTE, puts it more bluntly: “Black kid here, black kid there, white kid…nowhere.”

To address the subject, the students conducted around 30 interviews with experts and academics with a broader understanding of the subject. Then, equipped with the training they’d received through Epic, the students developed their characters and improvised scenes, which they use to develop a formal script, under the direction of Epic cofounder James Wallert.

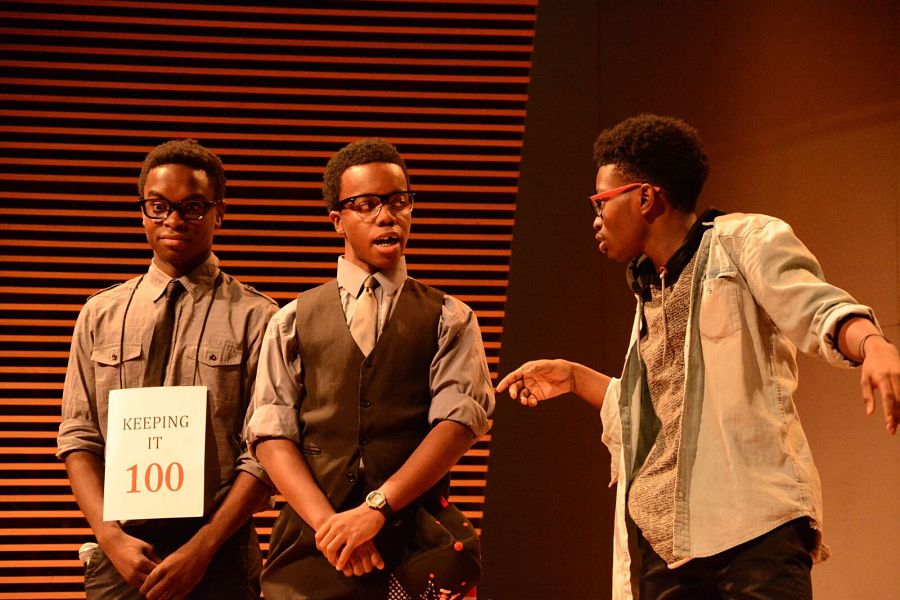

Knowing the way it was made, it’s unsurprising that Laundry City itself—which is essentially a collection of satirical sketches—is heavily reminiscent of sketch comedy by the likes of the Second City. In the debut performance I saw at Teachers College last month, the actors elicited more laughter than anything else. In one scene, Green and NEXT member Melysa Hierro play siblings who share a bedroom. Green’s character is trying to convince his sister to allow him to put a border between their two sides so they can have a “separate but equal bedroom.”

In another scene, the actors create a “separate but equal home school,” where one student gets to take class in the living room from a real teacher, while the other is relegated to a backyard garage—complete with metal detector—to take classes with the deranged “Uncle Buck.” It’s all very creative, very biting, and intelligently subversive.

Russell says that a central lesson that Epic tries to impart is that humor can “unlock the potential for change.” That’s certainly something that comes through in Laundry City. In the play’s final scene, which offers a stark break from the humor of the rest of the piece, the performers directly recreate pieces of the interviews they conducted, changing from over-the-top characters to ones they’ve met in real life. So it’s no surprise to hear that part of Epic’s training involves studying the work of Anna Deveare Smith.

Clearly, the students have garnered a keen understanding of theatre’s power as a tool for social change. Hierro speaks to theatre’s ability to send a message, arguing that having something to say elevates the performance itself. “There’s always going to be an objective,” she says. ”That’s when you really hit the ball out of the park.”

Ultimately, the students say, Laundry City is an attempt to ask questions about school segregation, not necessarily provide solutions. “We purposely want to get you confused so we can show that there’s no one answer to this question,” says Green. Osbourne expands on that, saying, “We went into interviews thinking that we were going to get one straight answer…[but] even today, we don’t know what the answer to the question is.”

Still, it’s allowed them to get their voices heard and engage in the larger social dialogue surrounding school segregation. And that seems not only fair, but crucial. Green himself thinks of it this way: “We are the primary source.”

Gabe Cohn is an NYC-based journalist whose writing has recently appeared in American Theatre and Time Out New York.