Director Jack Hofsiss died last month at the age of 65. Best known for directing the premiere of The Elephant Man on Broadway, he also worked as a casting director and directed for film and TV.

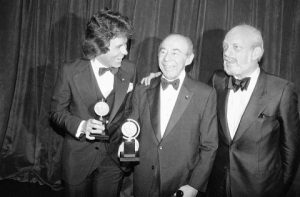

Jack Hofsiss was, among many things, a man of patience, endurance, and resilience—and, of course, tremendous talent. In 1979, at the age of 28, he became the youngest director in theatre history to win a Tony Award for his work on Bernard Pomerance’s The Elephant Man, a play about a cruelly deformed man, John Merrick, and his efforts to adapt to society in late 19th-century London. Reviews were rapturous. Walter Kerr called the production “a strikingly original theatrical achievement.”

The staging of The Elephant Man captured Jack’s unique style of directing, which combined a theatrical and cinematic vision; sparse and rhythmically precise, it incorporated stage versions of dissolves and close-ups. Jack viewed the stage as a movie audience views the screen; he knew how the eye moves from face to group and back again. Always a perfectionist, he would watch rehearsals and performances repeatedly. He told me, “Seeing a show so often is like finding that you’re pregnant with child again, only it’s the same child as the last one.” He was never bored because he’d find something new, something significant every time.

Jack was also responsible for bringing the theatre and rock worlds together when David Bowie joined the cast of The Elephant Man (taking over for Philip Anglim). Bowie had seen the play a number of times, and he and Jack became fast friends. Bowie agreed to the role only if he could work with Jack. Already a success, the play ran for another year and a half to ecstatic reviews.

Jack went on to direct the television version of the play, and other projects for the stage and film and Hollywood beckoned, including the Jill Clayburgh vehicle I’m Dancing as Fast as I Can. Then, in the summer of 1985, he dove into a swimming pool on Fire Island, hitting his head on the slope. “Luckily I had friends over for post-disco breakfast, and they pulled me from the bottom of the pool,” he said. The accident left him paralyzed from the chest down, and he would use a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Fortunately, after a period of suicidal depression, Jack rebounded and resumed his work in the theatre. I first met him in 2008 at a 10-minute play festival at HB Playwright’s Theatre in Manhattan. One of my plays was on the bill. Afterward he said to me, “I was mesmerized by your work. You never lost me for a minute. You should expand this into a full-length play. Contact me if you do.”

After a stint with my writing mentor Craig Lucas, I did just that. For five precious years, Jack and I were friends and colleagues. He saw me through multiple drafts of that play—titled Undone—and drew the best out of me. His ideas never stopped flowing. I would get phone calls in the middle of the night when he would get yet another amazing thought about the play. “Make magic,” he would say as I embarked on each new draft. Never wanting to fail him, I did my best to “make magic.” It was worth every ounce of effort I put into it, and the end result was a play we’re both proud of.

“Making magic” was Jack’s mission in life. Virginia Woolf calls Shakespeare’s mind “incandescent.” That’s how I think of Jack’s mind: incandescent. Though his body had been partly disabled, his thinking remained as sharp and as brilliant as a diamond. Nothing could take that away from him.

I often wondered how Jack developed his ability to communicate. He told me, “That’s what directing is all about—making the actors think your idea is theirs.” He credited his Jesuit education with teaching him how to be articulate.

Born and bred in Brooklyn, he attended Brooklyn Prep and studied English literature at Georgetown University. His energies soon shifted to theatre. A production of Twelfth Night in Washington, D.C., caught Joseph Papp’s attention. When Jack returned to New York, Papp hired him as casting director for A Chorus Line at the Public Theater. From there his career burgeoned: Thomas Rabe’s Rebel Woman, three pays by Israel Horvitz, John Cheever’s The Sorrows of Gin, and more. He worked with actors such as Henry Fonda, Sigourney Weaver, Cloris Leachman, and Jessica Lange.

After his accident, the first play he directed was All the Way Home for the Berkshire Theatre Festival. Working again proved to be Jack’s lifeline. “It was a success,” he said. “Nothing is more rejuvenating than success, I promise you.”

But Jack had no illusions about his physical challenges. As he put it, “I have to no choice but to be committed to the positive in life, because if I focus on the negative, I’m sunk.” He continued to direct more plays: a revival of The Subject was Roses for the Roundabout and a revival of The Shadow Box for Circle in the Square. His most recent effort was an Off-Broadway production of Albert Innaurato’s Doubtless in 2014. He also taught directing and acting at HB Studio and at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts.

“When you go to the theatre, it should be an event,” he said. Being at the theatre with him was always an event, whether he was the director or an audience member. To have known him, worked with him, been in his orbit, was a great gift. He taught me that an artist must have both humility and confidence—a lesson he had had to learn himself.

When Jack returned to the theatre after his accident, he told People magazine, “My happiness is within now, based upon what I’m doing and my own self-satisfaction. I’m capable of making myself happier than I ever was before.”

I hope that was true. He deserved happiness. He was certainly the cause of much happiness in others. His work and life will never be forgotten.