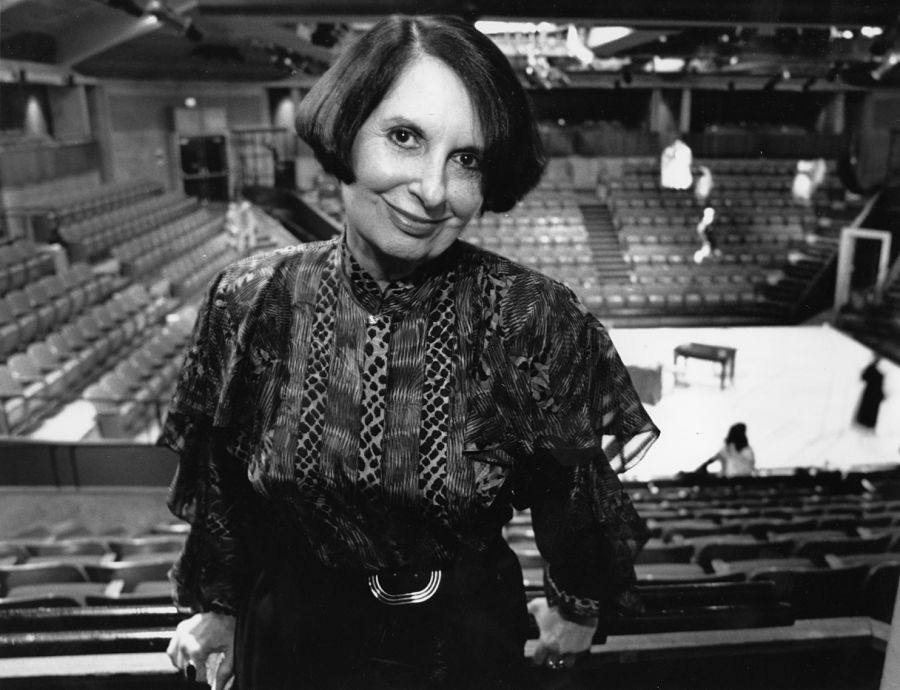

I’ve been struggling since Zelda Fichandler died at the end of July to come up with a suitable analogue for her outsized foundational stature in the American nonprofit theatre. Was she our George Washington, the level-headed general turned clear-eyed executive? Surely her four decades at the helm of Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage, which she left only to head New York University’s graduate acting program, had a founding-mother patina about them. Or was she our Steve Jobs-like innovator, making something seem inevitable and indispensable that we didn’t even know we needed before it appeared? The regional/resident theatre movement we now think of, for better or worse, as an entrenched fixture of the U.S. and world theatre was not solely her handiwork; like Jobs she had partners, and she built on the ideas of earlier mavericks, in her case especially Margo Jones. But Fichandler can claim a large part of the credit for making theatre outside the commercial capital of New York City not only a force to be reckoned with but almost a force of nature—a part of the given cultural landscape that simply wasn’t there a half century ago but which now even (perhaps especially) the commercial theatre couldn’t do without.

Or, to make the analogy more direct, was she our Stanislavsky, our Brecht—a leader both in theorizing and enacting the way to an ideal theatre of her own conviction and imagination? I’ve been eagerly diving into some of Fichandler’s writings (which will be collected in an upcoming volume by the estimable Todd London), and I mean no aspersion on the great theatre leaders of today when I say that I can think of few writers of any era—and I include critics—as tough-minded, searching, and circumspect about the many-faceted art and practice of the theatre. In a remarkable essay she wrote on the occasion of Arena’s 35th anniversary, and published by TCG in 1986, “Institution-as-Artwork,” Fichandler took sobering stock of the state of the movement she’d helped create, more or less ex nihilo, over the previous three-plus decades, alongside a far-flung breed of dreamers and doers, and wondered aloud, with breathtaking transparency: Is this really the world we wanted to build? She looked around at a field that had impressively professionalized itself but was at risk of what she called “the dry rot of institutionalization”; which was forsaking its commitment to well-trained, well-compensated actors and company artists; and which was too often at the mercy of bottom-line-oriented boards. If that litany sounds familiar, it’s because these dangers are still with us, unvanquished.

So, though, is the ever-renewing potential of this human-scaled art. I like to think that Zelda would be heartened by this issue, not only for Laurence Maslon’s lovely memorial tribute to her (expanded online to include his among several), but because our season preview shines a light on the fertile new-play landscape in the U.S., and because there are two richly satisfying stories about an oft-neglected practice that was central to Arena’s origins: rotating repertory.

It finally occurs to me that I don’t need any analogue to measure her against: She was our Zelda Fichandler, and we were fortunate to have her.

A version of this story appears in the October 2016 issue of American Theatre.