Putting on a single high-quality show is challenge enough. Creating an entire season is an even more daunting task. But repertory—well, that takes a special kind of crazy devotion.

“We have to rehearse changeovers from one set to another,” says Brenda DeVita, artistic director of American Players Theatre in Spring Green, Wisc., with an air of bemused resignation. “Before the summer we even measure everything to see how big each set is when it is packed up, so we can plan how to lay everything out in our storage unit. Otherwise repertory theatres like ours can run out of space, and then actors are trying to enter for a scene while maneuvering around the stuff being stored backstage.”

It’s not just the preparation of sets that makes repertory theatre so demanding. “It is murderous on our overworked and underpaid production staff,” declares David Ivers, artistic director at the Utah Shakespeare Festival in Cedar City.

Julia Rodriguez-Elliott, producing artistic director with her husband, Geoff Elliott, at A Noise Within in Pasadena, Calif., concurs, noting that while opening a show is always arduous, rep production teams go from “one hell to another—and it pushes the administration there too.” Repertory actors “have to be warriors,” APT’s DeVita suggests, to act in one show while rehearsing another. Costs are higher, Elliott points out, not only for the actors and set design but also because companies must pay extra for changeover crews.

With all those issues—space and storage, overburdened staffs and artists, escalating costs—there’s no wonder that repertory seems like an endangered species these days. That’s especially true, says Kimberley Jean Barry, director of stage management at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, since the Great Recession left many arts organizations curtailing budgets and ambitions. (Even in the United Kingdom, which has more governmental arts funding than the U.S., both Ian McKellen and Judi Dench have recently bemoaned dwindling support for their country’s regional rep, lamenting that its demise would damage the development of young actors.)

Even committed rep theatres have cause to step back and examine their choices. Rodriguez-Elliott says her California company occasionally revisits the concept to ask, “Why are we doing this? It is so punishing in so many different ways; we should not do it just because it’s what we have always done.”

Yet the answer always seems to be keep going. As Elliott says, “There’s a strange kind of alchemy with repertory.” OSF’s Barry adds that rep provides “enormous benefits and great joys” to those who tough it out. “The actors develop a shorthand and trust each other, becoming better artists in the process,” she says. “Repertory deepens the work in indescribable ways.”

Barry notes that Oregon Shakes, which often has five or six productions traveling to other theatres, believes so strongly in the value of repertory that in its most recent 10-year plan, OSF committed to exploring ways to tour not just single productions but pairs of shows in rep. That idea jibes with DeVita’s observation that the conversations and connections between shows in repertory provide benefits that are often “undervalued or not understood” by outsiders.

In Rodriguez-Elliott’s view, those values are both tangible and ineffable: “The energy of one show does indeed feed the other, but repertory also gives each show more time to build word of mouth.”

Amy Wratchford, managing director of the American Shakespeare Center in Staunton, Va., says the practice of repertory is a huge boon for her theatre’s education arm, because it encourages university attendance—students can come out to experience a week’s programming and cover an entire semester’s worth of plays in that time.

But ultimately the thing that matters—the reason to tough it out in the first place—is what rep does with and for the art. Theatre is inherently a collaborative medium, and repertory demands exponentially more teamwork.

“Repertory requires all the plays collaborating with each other,” DeVita says, “in every aspect, from every angle—not just the actors and the production team, but even the administration.”

For rep to run smoothly, she says, planning must also be an artistic endeavor. “The thing I love the most is that you have to be invested from all sides, and it takes an extraordinary amount of planning and focus. You have to have the ability to make decisions quickly, but also to have contingency plans for filling in the gaps.”

Rodriguez-Elliott suggests that having one play in rehearsal while another is running “brings an artistic vibrancy to the process and creates a conversation between the plays that energizes us, whether consciously or not.”

Repertory also nurtures actors, breeding better performances. Rodriguez-Elliott says actors often get pigeonholed into certain types, but repertory, with its need for actors to work in multiple plays, allows them to show what they can do with other kinds of parts, even if they may be smaller.

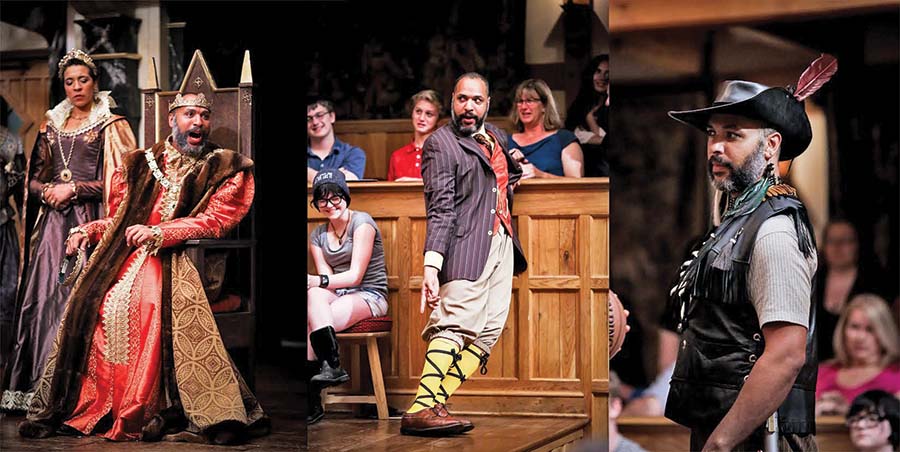

And this doesn’t just have benefits for the performers. “There’s a kind of magic” for audiences, Ivers contends, when they get to witness that sort of virtuosity and say, “Wait, didn’t I see the guy in this comedy playing Romeo this afternoon?’”

Indeed, many say there’s something about repertory that can bring out the best in an actor. As Jim Warren, artistic director at the ASC, puts it, “Having more than one play at a time in your brain and body means everything has to fire more fully and on different cylinders. It makes each piece better.”

DeVita adds that actors who have a small part in one play and a lead in another are more likely to remain fully engaged in their small role, because they’ll want that night’s lead to be as immersed and supportive when it’s their turn to shine. Having small roles in two or three plays can feel to an actor like “a weight has been taken off,” agrees Elliott, who is also an actor, and that can result in a “giddy and liberated feeling” infusing the performance.

For theatregoers, there’s a practical advantage to seeing multiple shows from the same company of actors over, say, a single long weekend. OSF’s Barry points out that the 100,000 people who regularly see OSF shows don’t all come from the Rogue Valley where Ashland sits; many come from Seattle, Portland, or the Bay Area, and they’re unlikely to travel to see just one show in a weekend. Repertory helps make a theatre like OSF—or Utah Shakes, American Players, and the ASC, all similarly geographically isolated—into a destination.

This year features a major new player on the rep scene. Patrick Dooley got his start in college as an actor with Shenandoah Shakespeare Express (which Jim Warren later transformed into the American Shakespeare Center), then went on to found Shotgun Players in Berkeley, Calif., in 1992. Though this last organization didn’t start out as a repertory theatre, Dooley always dreamed of returning to his roots. Recently, he toyed with the form by staging all three parts of Tom Stoppard’s Coast of Utopia in rep. And this year he’s celebrating the theatre’s 25th season by taking the full plunge: All five Shotgun Players shows are getting their own full runs, then will be worked into repertory with the others.

The initial reaction to his initiative was disbelief, Dooley concedes. “My producing director said, ‘Are you crazy?’ and my managing director asked, ‘How are we going to pay for this? What’s the financial model?’ And the union said, ‘We have no contract for this.’”

Luckily, Dooley says, his board “wants to see us try new things and get out of our comfort zone.” More good fortune came when, after months of negotiations, Actors’ Equity agreed to a contract for the performers that was workable for both sides. “I give the union a lot of credit for making this work,” Dooley says.

Shotgun Players even went one unusual step further last spring, performing Hamlet in repertory with itself: All seven actors in the show learned every role and drew beads (from an empty skull, of course) in front of the audience each night to determine who would play which part. “It’s chaos rep,” Dooley joked at the time. “An actor could play Hamlet every night or go 11 months without playing him until closing night!”

Most repertory theatres face a more straightforward challenge: to fashion a carefully balanced program while striving to create a conversation among the plays. “Programming can be a headache, but when you figure out the matrix it is so thrilling,” Utah Shakespeare’s Ivers says. DeVita concurs, pointing to King Lear and Death of a Salesman as plays written three centuries apart but both featuring patriarchs losing control of their families and “howling their frustrations at the wind.”

DeVita goes on to say she will sometimes hold off on a play till she can find the right one to pair it with. At A Noise Within, where each season comprises two sets of three plays in rep built around a theme, Rodriguez-Elliott expects the connections to work subliminally with audiences, though newsletter articles and post-show talkbacks often underscore the common ideas.

When the Bard is a theatre’s core repertoire, the concerns can be a bit different: Utah Shakes is planning to stage the entire canon over 12 years, and Ivers says he must seek a balance, frequently matching a comedy with a history and a tragedy, but also parceling out the works so audiences don’t come out for a weekend of staples such as Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Henry IV in one season and rarer items like Titus Andronicus, The Comedy of Errors, and Henry VIII the next. Warren adds that another important tactic is to put the most popular play up first, as it then gets the most performances in the repertory. “You don’t start with Pericles and get to Hamlet later,” he says.

One of the biggest challenges of doing repertory is the scenic design—or rather, designs. According to Elliott, “It’s like playing three-dimensional chess in finding the storage space.” Dooley agrees, citing occasions when set pieces have to hang from the ceiling with costumes up on racks; he also needed to rent a pod to hold furniture. He notes that he had to revise a recent budget to include an extra $3,000 to hire more people just to help with changeovers. And repertory budgets must also include more money for touch-up jobs on sets, Dooley says, because the changeovers create more wear and tear.

Rodriguez-Elliott says designers must be willing not only to share space with other designers but also to tailor their ideas to accommodate the need to constantly put up and take down each set. “The lack of choices is freeing in some respects,” DeVita comments, “and it can be exciting to think in ways you are never forced to think.” That might mean creating a set that can be folded up into a box in under an hour. Does every designer want to go there? Elliott diplomatically acknowledges, “There have been wonderful designers who are just not a good fit for repertory theatre.”

Casting, like scenic design, is inherently a very different animal in repertory theatre. “The actors will be living on top of each other for months, so you are trying to cast a company, not just a play,” DeVita says, adding that she often tries to make sure core members have at least one medium and one large role over a season to keep them busy and invested. Many rep theatres try keeping a core company together. But, Ivers notes, the number of actors willing to commit to (let alone handle) a season of rep is limited, “so we are all going after the same pool.”

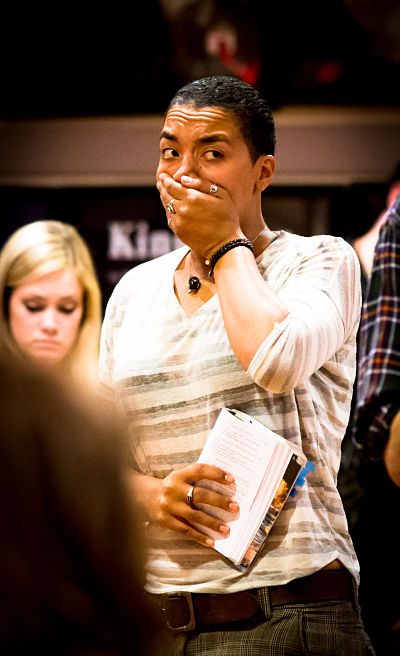

Casting is typically the purview of an individual play’s director, but rep has different demands. Barry notes that OSF has a casting team that works with the directors and tries to honor their wishes, though the giant grid of plays and parts to fill can take precedence. (OSF has nearly 800 performances and 900 educator events, and all the actors serve as understudies too, making their grid the most complex of all.)

Ivers says he and Brian Vaughn, Utah Shakespeare’s other artistic director, “lock ourselves in a room with spreadsheets,” trying to figure out how to fit actors into the roles they are best suited for across an entire season. “Our chart is like a board in a war room,” DeVita says, explaining that she tries getting directors the actors they want for the anchor roles; beyond those roles, logistics can take precedence. She says Evelyn Matten, production stage manager for 23 years, “has a computer in her mind” and sits in on casting to point out small details to consider: If two fairly equal actors are up for a smallish part in one play, Matten might say that choosing the first actor may cost that show four hours of rehearsal time per week because of their commitment in another show.

“I try to be inclusive of the directors, but I have to be transparent,” Ivers says. “You may say you have the perfect Mary Poppins for your show, but she’d have to play Katherine in Henry VIII as well, so what happens if she cannot speak verse?”

DeVita, who sits in on auditions, says just as some talented actors don’t embrace rep with the ardor and flexibility necessary to make it work, not every director is willing to play ball, both in casting and in sharing actors during rehearsal time with another play. “I’ve had a director say, ‘I don’t want to have to care about that.’”

Each rep company takes a different approach to juggling rehearsals, based in part on the number of plays, theatre space, and actors they have. At Utah, instead of eight-hour rehearsal days devoted to one show, days are usually split between two different shows. American Players has a six-week rehearsal process, but most actors are prepping two productions at once. OSF has an unusually long 11-week rehearsal period, and that’s because, with all the shows in the works at any given time, a director may have a great run-through on Saturday and not be able to assemble their cast again until Tuesday. (The company’s union contract also allows for brush-up rehearsals for all 11 shows for the casts and understudies.) The American Shakespeare Center rehearses one play at a time until it opens, but they have only 15 days of 8-hour rehearsals. “I think it makes for a smoother creation of the shows this way,” Warren says.

While many rep theatres do have loyal audiences who return year after year, the question for their marketing departments is often: Is it better to sell individual productions or the repertory brand itself?

“We don’t have the time and money to advertise each title, so we do institutional marketing,” says the ASC’s Wratchford. Meanwhile, at A Noise Within, at every performance they make sure to remind audiences that there are other shows going on in the same theatre that attendees can come back and see without waiting for weeks or months, Rodriguez-Elliott says.

“You don’t want the shows subsumed by the concept,” Dooley says. “It’s about trying to find a balance—you need to make sure each play gets its own special light and is not just part of a big machine. But you also are trying to make sure it is really well explained what we are doing here.”

It’s too early to tell whether Dooley will still be doing rep next year. He knows there’s a chance it may feel like a “novelty,” but he is hoping that there’s so much enthusiasm for it that the board will at least give him the chance to do the final three shows of the season in rep.

“We want to show that the plays are enhanced and more vibrant in repertory, and are not compromised,” he avers, adding that doing shows just once a week in repertory brings each performance “a little more adrenaline, an extra level of urgency.”

Stuart Miller is a freelance journalist based in New York City.

A version of this story appears in the October 2016 issue of American Theatre.