When the great playwright Edward Albee died last Friday, Sept. 16, we asked actor and playwright Tracy Letts to write a tribute. But for an artist of this stature, to quote another great American playwright, attention must be paid. Below are recollections from a few of Albee’s closest collaborators and colleagues.

“I Didn’t Hear the Comma”

I’m writing this note about Edward while still in a daze, still talking about him in the present tense, which I hope would amuse him, still unable to believe he isn’t here. The first play of Edward’s I directed was All Over. I recognize the irony of this as I write, since the play is a death watch for the Great Man, who lies in a bed silently all night upstage of the action. In rehearsal we gleefully imagined him to be Edward. The other characters are his Wife, his Mistress, his Children, and his Doctor, Nurse, and Best Friend.

When I asked him if I could have the rights to it, his response was typically terse. “Of course. What took you so long?” I was to direct it with the great Rosemary Harris, the sublime Michael Learned, the wicked genius Myra Carter, and a sensational supporting cast. I remember the first run-through in the old rehearsal room at the McCarter as if it were yesterday. Edward sat dead center, six feet away from the actors. Rosemary was so nervous her tongue stuck to the roof of her mouth, and yet she managed a flawless, shattering run-through, as did the entire company. When she spoke her final lines, “Because I am unhappy,” the sobs overcame her, as they did from first rehearsal in Princeton to closing night in New York.

Edward gave only one note. He pointed to a line in the script and said: “I didn’t hear the comma.” For those of you who didn’t know him, I must state what to the rest of us is obvious: He wasn’t kidding. Also, since it was his only note, I was later to learn, he was actually pleased.

Edward wrote all his plays as if they were musical scores. He referred to them that way. Over my next four productions with him, I learned from him how to read each one as he intended it. Not one was the same. What was the same was the actors had not only to play the notes (the words) but also the dynamics, phrasing, and articulation. Sloppiness was anathema to him. Ferocious accuracy was paramount. Beyond that, he demanded unflinching emotional truth moment to moment. He also expected you to get all his laughs, consistently. He was, in short, a task master. But to me and a few others, he was a very loving and benevolent one.

A great man has fallen, but his astonishing work will live on and on and on and on. Thank you, dear Edward. It is not all over…

Emily Mann, artistic director/resident playwright, McCarter Theatre Center

A Transformative Test

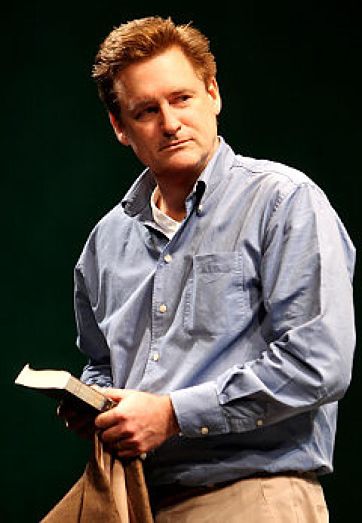

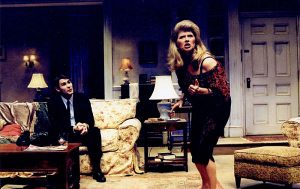

In the fall before the spring of 2002 when I would play Martin in the Broadway premiere of The Goat, I got a call while in L.A. from my then-agent. She reported about some activities on my behalf, then in an aside said, “Oh, and then there is this play that you would have to audition for and I don’t think you’ll want to do because of the subject matter, but it is written by the famous playwright Edward Albright.”

I had never met Edward Albee but of course I knew whom she meant to say, and I realized that even if not all of the movie industry recognized the name, I would be reading a new Albee play that hadn’t been produced or published. I was ignited, and felt it was honor and a challenge. The decision to pursue it was one of the most important of my career, and one that proved to be harrowing and transformative. I had never worked with as distinctive a mind and talent and character as Albee’s.

At 48 I had the intuition that everything I had done prior would be tested by the prospect of working on this play. I hadn’t done theatre in more than a decade, and the play, it turned out, is about a man who carries a secret about a very socially unacceptable passion: He has fallen in love with a goat. I got the clear impression that other movie actors had passed promptly when offered the shot at it. At a Christmas party a studio head listened to my synopsis of the play I was about to do and said, “Get out of it.”

Before the first read-through, our steady, supportive director, David Esbjornson, turned the introductory remarks over to Edward, who began with a correction to something I had said earlier: “The name is pronounced ‘AWL-BEE’. ” I felt as if I’d been as crass as having made a reference to “Al” Einstein. At the end of the read-through he said, “That is exactly the play you will be performing when we open in two months. I believe it is a good play and your job will be to not mess it up.” He was clearly conveying that there would be no rewriting, and that we needed to never entertain any thoughts that some of us might uncover some weaknesses or have impertinent “suggestions.”

Later, as we began the process of previews, even Edward had came to realize that some adjustments needed to be made. The last seven minutes of the play as we were then performing it began with the bringing on of a dead goat. Edward referred to the play as a tragedy, but we couldn’t seem to sustain the intended serious tone. Our dialogue was in danger of imploding with strangely riotous laughter from the audience. The curtain call for the actors was the hastiest retreat any routed army could manage. We all were sustaining a degree of embarrassment that could have pushed any of us into a hysterical condition that would have made even hearing the word “theatre” toxic and terminal. All would have seemed hopeless if it weren’t for Edward’s steely resolve and surgical editing. The last seven minutes became three, and we could finally keep the reins on events to allow a fairly managed crowd response at the end.

The Goat proved very disturbing to many and highly praised by enough. It went on to win the Pulitzer and the Tony. Edward thought sufficiently positively of my work to invite me to work on his reenvisioning of his iconic Zoo Story into a two-act evening now called At Home at the Zoo. I wasn’t the only actor who loved working with him while remaining always prepared to feel embarrassed in his company. But I was so honored by his wink and sudden smile. And his plays demanded a truth from me that transformed my ideas of what it meant to have strong commitment and courage in the theatre.

The Goat proved very disturbing to many and highly praised by enough. It went on to win the Pulitzer and the Tony. Edward thought sufficiently positively of my work to invite me to work on his reenvisioning of his iconic Zoo Story into a two-act evening now called At Home at the Zoo. I wasn’t the only actor who loved working with him while remaining always prepared to feel embarrassed in his company. But I was so honored by his wink and sudden smile. And his plays demanded a truth from me that transformed my ideas of what it meant to have strong commitment and courage in the theatre.

Bill Pullman, actor

Love With a Crooked Grin

Edward Albee, in his great and mysterious way, seems to resist my efforts at organizing things into the necessary but artificial divisions of years and paragraphs. So I thought I’d just, in Edward’s words, get up on my hind legs and speak.

My life and my understanding of it are completely changed because of knowing Edward. He was a genuinely supportive, caring, and honest friend to me, and to many, many playwrights. He was also really tough—someone who loved the world and the people in it in a way that could seem somewhat distant and nonlinear but was in fact very solid and constant and dear. He loved you with a crooked grin, sometimes, but it was real and it was true. He liked the animal part of people and the peopley part of animals, and had a lot of pets over the years.

I used to cat-sit for him. His cat, at that time, was named Snow. I always found it charming, almost devastating, that this master of the English language would choose the same name for his pure white kitten that an eight-year-old child might also pick. Snow would sit in his lap very quietly and he would gently scratch behind her ear, no different from a million other cat owners and their Snows, and I think it was probably a relief and a joy for him to sit there in that way and not worry, for a little while, about turning the world upside down or getting it right-side-up again.

Edward called most years to say Merry Christmas. The fact that it wasn’t every year made it more meaningful and human. I mention these small things to remind myself and those who may not have known Edward that this was a person who was, after all, utterly real. I remember he had a rain jacket, maybe red, and I don’t know why this makes me want to cry. Picturing Edward, looking out the window and up at a gray sky, heading out to a rehearsal or the grocery store, putting on a red rain jacket with a hood. He might enjoy the melancholy of that image, but would be happy for us to keep moving, so we shall.

We were at a theatre event one year and Edward said he’d recently had eye surgery and was able to see the world more clearly than he’d seen it in 20 years. He paused for a moment and then said quietly, “Ugly.” Quip is not the right word, because it sounds too easy. There was a hard and terrible truth in the brief, funny things he’d sometimes say. “I can’t tell young people apart.” But there was love and tenderness and curiosity too. This is, after all, a man who at the age of 78 went almost around the world to see Easter Island. It was one of the constant themes of his work: that you must participate in life, that nothing could be worse than to realize that your life had gone by and you hadn’t really lived it. I hope it felt from the inside at least a little like the long and beautiful Roman Wall of a life it looked like from the outside.

I have always, since I’ve known him, imagined that Edward was born in a tuxedo. A just-right tuxedo with one errant pocket flap that he needs to smooth down before he walks up to a tiny podium to tell us who he is and where he’s come from. How I like to imagine him making his exit is as a beaming, unworried, and completely loved person, maybe a young boy again somehow, a red ribbon that says “Participant” pinned on his shirt, as he gathers the curtain and grinningly tries to find the break in it.

I did not visit Edward in the last couple years and I feel terrible about it. I don’t say this as if he was some miserable soul and I a would-be saint who could have cheered him with my presence. Or to take the spotlight with my shame. I say it because I really loved the guy and I wish I’d gone to see him and now it’s too late. And I say it here because Edward was someone whose life was devoted to the hard work of learning, of turning messy pain into a simple, share-able lesson, and a hope that with some thought and attention we might all become slightly better animals; and I want to try to follow that great example.

So I’d like to close by saying to you, to us, very humbly: Make sure to spend time with your friends. Go visit. Try to call, most Christmases.

Will Eno, playwright

No Regrets

I met Edward during my first week in Houston. I had heard that he was teaching in town and had asked how I could get to see him. The next day he showed up at the theatre, unannounced. I was thrilled to meet him—and a bit apprehensive. I had heard he could be “short.” We talked for a bit and I asked him to direct a production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? for the first season I was planning. He asked, “Why?” Surprised at the question and a bit unnerved, I stammered something about how it’s “the great American play.” He deadpanned that it “might be”—and agreed to it.

His production was the first of a dozen or so we did together at the Alley in the seasons while he was an associate director here. He loved Houston, as it turned out, and loved teaching. And the relationship with him changed my life. It also changed the lives of many of the artists who’ve worked here. He loved the resident company idea and was intrigued to see actors whom he’d seen in Chekhov and Brecht at the Alley do his plays here. He was a great “attender to, and of” plays and a fantastic house “critic” (as much as he detested the journalistic variety). I loved his responses to the work, even when he didn’t like it: He saw our Comedy of Errors twice, complaining both times about the ad libs we had sprinkled through. “Perhaps not his best play,” he said, “but he did write it, for Christ’s sake.”

He directed Alley productions of his own work—The Play About the Baby, Marriage Play, Virginia Woolf, The Zoo Story, The American Dream, The Sandbox, and others—and several times helmed productions of Beckett for us. “Sam” was his favorite writer, as we all knew, and he approached the plays with an acolyte’s devotion and a scrupulous attention to the text and (no surprise) to the stage directions. We all know Edward’s vigilance about the integrity of his own work; with his Beckett productions it was very clearly practiced. One of the plays he did was Ohio Impromptu. It was a beautiful production in every way, and Edward was very moved every time he listened to it. He asked me once if, given the short length of the piece, we might offer to do it twice for each audience? I replied as gently as I could that the play being about what it’s about doesn’t allow for that—which he, of course, knew. But he also knew how much it reverberated in him. We only performed it once each night, as Sam would have insisted, but Edward had been tempted.

In 2000 he suggested that he might direct The Play About the Baby (“a rollicking comedy about how much pain and loss we can take, and when we can take it”). He had “learned things” about the play during the London premiere and wanted to put his new thoughts onstage. We agreed and Edward set to work. Unique in my experience, I watched him cut and rewrite during rehearsals—he said, “I spoke to the director about the changes, he trusts me.” One change involved the entrance, near the end, of a huge, monstrous baby, diapered, on all fours, crawling alarmingly toward Marian Seldes, then making an abrupt turn to crawl, ever more alarmingly, toward the audience. “I don’t usually stage the metaphor,” he said, “but one wants to see what they understand and what they don’t. I don’t want, ‘Oh, Mr. Albee, you’ve written another play about non-existent or destroyed babies. I haven’t. Look: There it is.” And indeed, there it was—for two previews. “That was enough to make the point,” he concluded.

We made a festival of some of his works in 2003, and I took on the task of directing Woolf. Edward asked if he could attend rehearsals. I couldn’t very well say no, but I knew we would all—all of us, actors, me, designers, small staff—obviously feel completely strange given the genius elephant in the room. He came to most every rehearsal, and he was fantastic. Quiet and attentive and never offering a comment or a critique of a moment. At the end of the day, he and I would talk, sometimes for hours, and he always praised the actors and the work—and then he would offer a startling insight. It’s hard to surprise me about this play; I’ve known it for a long time. But he did, every day.

I urged him to be willing to talk to the actors, and so he did. Whenever any questions came up—about George’s parents, the bar on Tenth Street near Waverly Place, the bar in Berlin, the genesis of the telegram—he spoke, usefully, and at length. He was in a fine and introspective frame of mind, and I had never before heard a writer, especially one so famously unwilling to explicate his plays, share with a cast some 40 years of living with a masterpiece. He admired all the work we were doing—until the first preview, where the audience roared throughout the first act. Edward was a bit peeved: “Why are they laughing so hard?” “Well,” I said, “I think it’s the funniest first act in American theatre.” He thought, I think, that the audience was enjoying itself too much. But by the third act the house had profoundly changed; Judy Ivey and James Black, to my mind, gave the definitive account of Martha and George’s Passion and Gethsemane, and the play’s end was met with fully 30 seconds of silence before a different kind of roar went up. Edward looked at me: “Very good. Finally.”

We did many talkbacks together. At the one I remember best, after Play About the Baby, yet another audience member asked him what his play “was about”—a question he always hated (“It’s about 95 minutes” was a standard response). But this time he said:

When you come to the end of your life, the most awful thing is to think you haven’t lived. Regret over what we have done is okay, but regret over what we have failed to do or chosen not to do is unforgivable. And I suppose that’s a theme that runs through all my plays.

Ave atque vale, Edward.

Gregory Boyd, artistic director, Alley Theatre