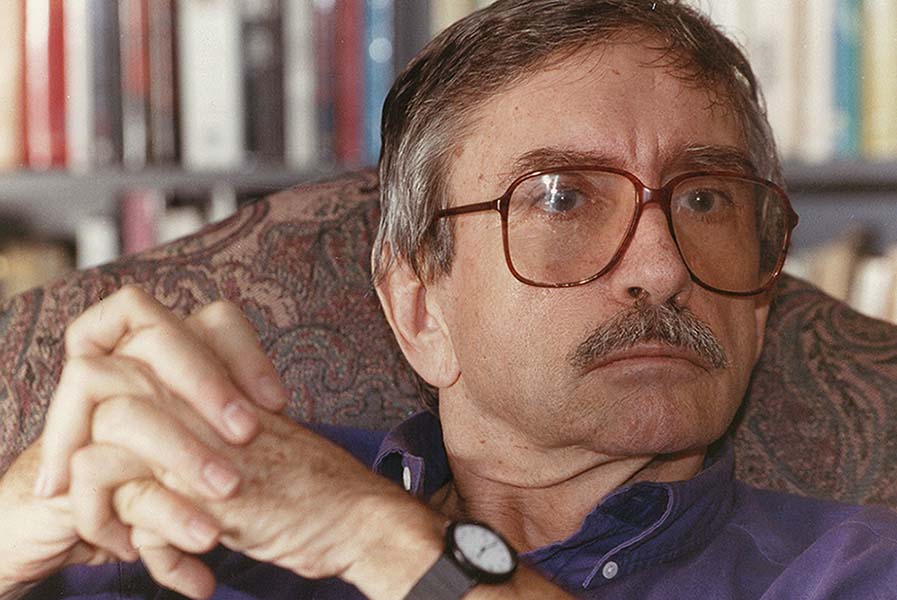

Much has been written, and will continue to be, about the late, great Edward Albee, who died on Sept. 16 at age 88. Widely considered the foremost playwright of his generation and one of the greatest of the 20th century, he is recognized as the first American dramatist to introduce the theatre of the absurd on our shores and help ignite the Off-Broadway movement of the 1960s.

Winner of three Pulitzer Prizes, he is best known for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, a devastating drama about marriage and the American Dream. But all of his plays, 30 in all, deal with similarly urgent themes and others pertaining to family, sexuality, and identity. “Who am I?” is a leitmotif that echoes throughout his unique oeuvre. Indeed, it’s question that haunted Albee himself as well as his characters (he was adopted as an infant and never knew his biological parents).

Yet little is known about the “other Edward Albee”—namely, the teacher and the mentor of young playwrights. During his partly self-imposed exile from the New York theatre scene, he spent more than a decade on the faculty of the University of Houston (1989-2003). After he moved back, I had the great privilege of watching him in action numerous times in my own classroom at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, where I teach a course in Forms of Drama in the Department of Dramatic Writing. He was wonderful.

Here’s how this fortuitous arrangement began: I first met Edward in 2003 while researching a theatre biography I was writing on Vaclav Havel, the Czech dissident/playwright/president whom Albee had championed during Havel’s imprisonment in the 1980s. In a subsequent conversation, I summoned up the courage to ask him to come talk to my own graduate writing students (you needed courage when talking to Edward, who was famous for his prickly persona). To my amazement, he instantly agreed—on one condition: that the students not be told of his visit in advance, and that it remain a surprise.

That began a ritual of visits that lasted every spring semester for almost a decade. Edward would arrive, unannounced, at the beginning of the class for which his plays had been pre-assigned for discussion. I’ll never forget the look on those shocked students’ faces, and their gasps of surprise, delight, and (I daresay) a tinge of fear.

“My first reaction when Mr. Albee walked into our classroom was one of awe,” recalls Joe Mango (class of 2014). “To be sitting among a living legend, especially as an aspiring writer—what an inspiration! I’ll never forget what he told us: ‘Invent playwriting every time you write a play, since that’s the only way to do anything new or evocative.’”

As it happens, that is only one of the many gems that Edward imparted to our young writers during those visits over the years. He had an unerring sense of the dramatic—indeed, his visits were a kind of performance. “Ladies and gentlemen: this is Edward Albee,” I’d introduce him. “That’s not my name!” he’d snap, and launch into a revelation of his adoption and his painful lifelong search for the meaning of family. Though by pre-agreement his visits were to last 45 minutes, after an hour and a half he was still holding these young writers in his thrall, hurling out pithy words of wisdom on writing for the theatre (peppered with the occasional profanity) in his crusty style.

I’m grateful to my students—Joe Mango, Cory Terry, Kimberly Barrante, Liza Case, and others—who recorded some of these pearls over the years and shared their notes with me on this occasion. Here are some of them:

On becoming a playwright:

“Watching The Zoo Story, I realized: That’s who I am—a playwright. Writing that play felt like coming home. It felt right.”

“Most writers start as poets and learn to stop.”

On the dramaturgy of his plays:

“There’s no such thing as a one-act play. All my plays are full-length. Every play is full to its length.”

“Length has nothing to do with the duration of the piece; it has to do with the duration of the experience.”

On learning from Pirandello, Beckett, and Chekhov:

“It’s better to learn from good people than from bad people.”

“Learn from the writers you admire. Don’t imitate, don’t copy. Learn how they do it, then figure out how to do it your own way. That way you don’t get compared to anyone.”

“Economy, beauty, precision—that’s the essence of Beckett. If he wrote three beats and you try to do it in two, it won’t work.”

On specific plays:

The Sandbox: “It’s my only play with no mistakes—because it’s only 11 minutes.”

“I modeled the character on my own grandmother. She was the only member of my adoptive family that I liked, though I must say that I liked my character better.”

A Delicate Balance: “People are terrified sometimes and need to be taken in and loved.”

The Goat: “There are a lot of things that we write about that people don’t like to think about. And that’s what we should write about.”

“I’m making them have a reaction to something. How marvelous.”

Laying an Egg, an unfinished play that would have been his last one: “Whenever I get the opportunity to destroy my career, I can’t resist it.”

On the creative process:

“I get things in my head and I have to get them out of my head so I can walk around and do other things.”

“I don’t have ideas. I have people. They meet. Things happen. They are changed. Find out why these people are in your head. Eventually they’ll say: ‘Write me.’”

“I’ve never written myself or someone like me into a play, except the silent 17-year-old boy in Three Tall Women. I don’t think I’m particularly dramatic.”

“The characters you write in your head must be as real as a real person.”

“You have to become your characters, not the other way around. You must base his/her reactions on how they would react, not how you would.”

“How long does it take me to write a play? My whole life.”

On the playwright and the actor:

“Do not write with the actor in mind. Actors play a role. Write the character, and then find the actor to best fill that role.”

“Every good actor does two things: He does exactly what the author intended and he does it his own way.”

On tragedy and comedy:

“Comedies at their best are more serious than tragedies.”

“Who says tragedy isn’t funny? Look at the Republican Party.”

On existentialism:

“You can’t not be an existentialist. I mean, do you live in the 18th century?”

On rewriting:

“Most playwrights give up the control they were born with.”

“I am always trying to edit myself and make it less literary. Literature should not call attention to itself. What’s important is what you’re saying, not how you’re saying it.”

“If it doesn’t push the action forward, cut it! Yourself. Don’t let anyone else do it.”

“Don’t get so enamored with what you’ve written that you can’t edit.”

“I’d rather write a new play than an old one.”

On other artistic pursuits:

“I was a terrible novelist.”

“I realized that Bach was going to do a lot better than I ever could. And if you can’t be as good as Bach, why bother?”

On breaking the fourth wall:

“If the characters are real and the audience is real, why shouldn’t they talk to each other?”

On the rehearsal process:

“Some playwrights should not be allowed in the room when their work is being done, because they keep changing things just because people tell them to.”

“I sit in rehearsals. And I cast, too. I’m best at everything. I interfere with everything.”

“I like to cast the first productions of all my plays because I like to take my own credit and my own blame.”

On directing one’s own plays:

“You probably know more about your own plays than you do about Chekhov’s plays. So the virtue in directing your own play is you’re a little closer. But you should only direct if you have something to contribute.”

On producers:

“It’s nice to have a producer who’s not a thief—somebody who’s interested in producing the play you wrote.”

On the critics:

“Over a 10-year period, some of your plays will get much better, and some of them will get much worse, depending on the imbecility of the critics.”

Advice to young playwrights:

“Don’t lie!”

“Tell as much truth as you know about what the characters are doing. Write about something that hurts or else you’re wasting your time.”

“You have to write what interests you. You have to interest yourself in order to interest anyone else.”

“Offend some people. If you don’t offend anybody, you’re writing slop.”

“Any work of ours that’s not dangerous is not worth paying attention to.”

“Theatre is what you can get away with.”

“Every time you write a play, you should invent the form. Write the play no one has ever written.”

“If you’re lucky, you find out who you are, by chance, and what you should be doing, by chance.”

“Good things do happen by accident.”

“Most people want to live life without wanting to participate in life. And you should want to participate.”

Emerging from these quotes is the portrait of an Albee that audiences may not have had the chance to meet: a warm-hearted, generous-spirited, wickedly funny, brilliant, mischievous, lonely, giving, and (yes) loving human being.

I trust that other educators will come forward with their own stories of Edward’s visit to their classrooms, and how he changed the lives of so many young writers. These visits were gifts as great as his plays. They remind me of a line in Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, a play about a teacher who explains to his students what teaching means, and what Edward personified. It is summed up as a directive: “Pass the parcel. Take it, feel it, and pass it on. Not for me, not for you, but for someone, somewhere, one day. Pass it on, boys.”