It was a moment of reckoning for Chicago Dramatists. With a leadership transition, the death of its founder, and mounting financial pressure, the 37-year-old institution needed to take a cold, hard look at its identity and priorities. The leadership decided to stop producing plays.

This is not to say that the company has stopped making plays. Chicago Dramatists now joins the ranks of several venerable new-play development institutions that don’t produce work—most notably New Dramatists and the Lark in New York City, and the Playwrights’ Center in Minneapolis. Instead of being guided by the vagaries of audience attention and box-office numbers, these laboratories are able to pursue a more holistic approach in serving the needs of the playwright, and have thus left an indelible mark on the ecology of the play development sector.

“As soon as we made the decision, a huge weight was lifted off our shoulders,” said Chicago Dramatists artistic director Meghan Beals, who took over the organization a year and a half ago, following the death of founding artistic director Russ Tutterow. “It was impossible being both a producing organization and a new-play development organization. Those are two different hats a lot of the time. Either we were going to be producing with a distinct personality and all of the amazing dramaturgical auxiliary programming that makes a truly successful launch of a new play, and a truly successful conversation with the community, or we perhaps shouldn’t be doing it,” Beals explained. “Now we can invest in the voice of the writer and the plays that he or she is writing now, or the plays he or she will be writing over three or four or five years with us. It’s much more personal than having to sell a show.”

The ways in which these organizations—“the 24/7, year-round centers,” as the Playwrights’ Center’s Jeremy Cohen called them—go about supporting playwrights overlap, and the influences among them are clear. But as John Clinton Eisner, artistic director and cofounder of the Lark, put it, “Even if we completely duplicated each other, there still wouldn’t be enough space, opportunity, or resource for the work that needs to be done. It’s kind of excellent that the organizations have slightly different missions and do slightly different things, but also that we meet together frequently to work stuff out, so we can figure out how to support and enhance and leverage what we each have.”

Indeed, Beals is now drawing on a research-gathering mission she conducted as part of a TCG continuing education grant five years ago, when she served as associate artistic director for Chicago Dramatists. “I was able to travel to a lot of these organizations and interview writers and leaders to figure out what is working well, how they talk about the work, how they support the writers,” she said. “We have taken that list of methods and programs and best practices, and we’ve seen what’s applicable to us.” Chicago Dramatists is now primarily focused on its resident playwrights, who can access development support for a six-year term (with the option to re-up for three more years), as well as a national membership network, open to anyone. Readings, workshops, and public-access classes continue to make up the organization’s portfolio.

The Lark, meanwhile, offers eight fellowship programs, with significant financial support and artistic resources; global exchange initiatives with Romania, Russia, the Middle East, China, and Mexico, among others; and a roster of ongoing programs, such as retreats, writers’ groups, and career intensives. The Playwrights’ Center houses up to 40 playwriting fellows at a time, both in six smaller fellowships, funded by the Minnesota-based Jerome and McKnight Foundations, with stipends and travel support, as well as its core writer program, with 25 to 30 playwrights at any given moment, who have flexible access to workshops, public readings, and promotion for a three-year term (with the option to reapply). The Playwrights’ Center is also a membership organization, offering resources to 1,500 members worldwide, and works with roughly 100 theatres to connect them directly with playwrights and assist in developing work.

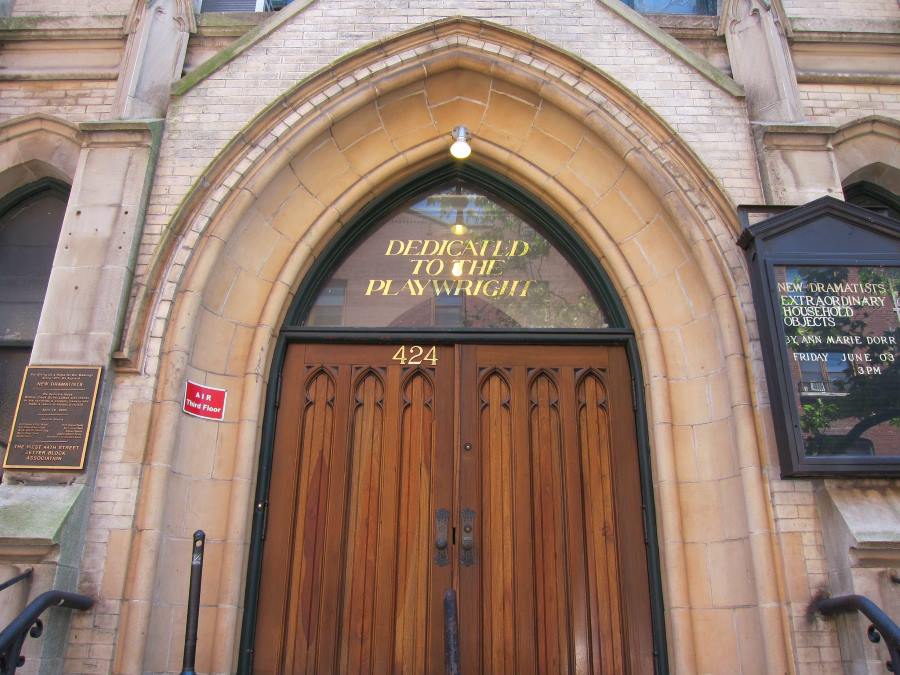

New Dramatists structures itself so that each resident playwright (roughly six to eight are selected by an outside committee each year) is the artistic director of their own seven-year-long new-play laboratory—a definition that could manifest in any given period as a closed reading of 10 pages of a playwright’s work by peer writers, or a more fully realized workshop with professional actors and an audience for a play that is ready for its industry close-up. Because resident playwrights sit on the organization’s executive committee, programmatic and ad hoc support shifts over time, reflecting the needs of the moment.

“At any point we could look at a snapshot of the history of New Dramatists and have a sense of what playwrights needed then, where their focus was in any given generation,” said current artistic director Emily Morse.

It also says something broadly about how playwrights have found ways to get their needs met that seemingly every 15 to 20 years one of these powerhouse play-development organizations has sprung up, blossomed, and stuck around.

In 1949, Michaela O’Harra—someone we might today dub an “early-career playwright”—wrote to Broadway actor and playwright Howard Lindsay after hearing him speak at a Dramatists Guild meeting, asking if she might send him her “Plan for Playwrights,” an ambitious outline for an organization to support “new dramatists of proven potential.” O’Harra proposed the development of playwriting craft through discussions, readings, and workshops, as well as creating opportunities—by virtue of being a group, rather than lone individuals—for young playwrights to meet their established counterparts, and simply to see more plays and observe the rehearsal process.

“Her vision, her notion, was that playwrights were each other’s greatest resource,” noted Morse. “Imagine the theatre landscape at that time. All there was was Broadway. There was no regional theatre, no Off-Broadway, no Off-Off-Broadway, and no graduate programs. There was really nowhere for playwrights to learn. Because of the nature of their unique creative process, so much is done in solitude. Michaela wanted to engage with other playwrights in terms of how they solved certain things, what they were writing about, how they got their material—all the things that in many respects are what playwrights are still talking to each other about now.”

Amazingly, Lindsay read the proposal and encouraged O’Harra to visit him in his dressing room before his performance of Life With Father, where he grilled her, in the five minutes before curtain, on her intent. In the end he concluded that the whole of her vision was “quite impossible. Our theatre is a disorganized, disparate lot of people who sometimes seem more set upon destroying it than doing anything to help it survive.” Nevertheless, Lindsay helped O’Harra set up what she termed a “craft discussion” with his cowriter, Russel Crouse, and a group of playwrights—which was successful enough for Lindsay to take the proposal to the Dramatists Guild, then led by Moss Hart, which voted to support it. The New Dramatists Committee set up shop in a storage closet of the Hudson Theatre (owned by Lindsay and Crouse), with a phone line, desks and chairs, and a filing cabinet.

The theatre landscape in 1971—when a group of playwriting students banded together in Minneapolis—was quite a bit different. To begin with, here were five playwrights toiling in Minnesota, not wandering around 42nd Street in New York. Regional theatres, an alternative scene, and graduate programs now abounded. But power in numbers could still prove transformative. By registering as a not-for-profit—originally the Minnesota Playwriting Laboratory—the writers (beginning with Tom Dunn, Erik Brogger, Barbara Field, Jon Jackoway, and John Olive) gained enough clout to get their work produced and even reviewed. As a team of peers, they could offer feedback for one another. And as an organizational entity, they could apply for foundational support. From that network eventually grew the Playwrights’ Center, and the Jerome Foundation’s early funding for playwriting fellowships cemented an organizational ethos that continues to this day.

The original impulse behind the Lark, founded by Eisner and several colleagues in 1994, in yet another theatre landscape, was to escape what they felt were a prevailing set of rules in the American theatre that at the time had come to prize efficiency over artistic innovation.

“Most of the new plays at that time were coming from England,” recalled Eisner. “It felt very mechanized.” He said that he and his colleagues “were thinking a lot about it, wondering: ‘Why does every rehearsal have to be four weeks? Why aren’t we doing different kinds of plays? And when we do new plays, why are they being quickly edited, reduced, so that they can be done in four weeks?’ That’s not strictly true of all that was happening in certain places, but there was a piece of the world where theatre was being served up to local communities as part of a national effort, as though everyone should eat their lima beans.”

Initially the Lark produced work as a natural aspect of new-play development. But after about two years, Eisner came to question whether they could support the development needs of playwrights while also producing plays, in a version of the same internal conversation Chicago Dramatists had this year. Eisner recalled a moment in which he had to decide whether to meet a playwright in a coffee shop to work on the ending of her play, or to wait for the lumber delivery for the set. He chose the lumber because it cost more. The playwright rewrote the ending—and the set design had to be changed.

“I started to realize how many theatre companies started small like us, and then continued to produce work, and it became about the next show and the next,” said Eisner. “I felt all of the suck of the organization moving into that. We decided that there was a whole part of process that wasn’t being attended to: to give artists agency over their work.”

Over the intervening six decades the existence of these hotbed centers—as advocates, as risk-free exploration labs, as networks—has arguably led the theatre field to a new understanding of the needs of playwrights, and to adapt accordingly. That, in turn, has freed writers to push the envelope even further on what it means to write and develop new work.

“We now have the advent of a lot of producing theatres of all sizes who are thinking about writers in new ways than, let’s say, 10 to 15 years ago,” said Cohen. “As a result we’re seeing a real shift in the field.”

Beals said that in 1979, when Chicago Dramatists was started, it “did three things: table readings, public readings, and productions, with nothing in between. Thirty years ago, you could develop a play sitting around a table. That was more or less the methodology. Then you just put it in rehearsal. Now there’s a much longer gestation period. Playwrights write in different ways. They write for specific companies. There are plays that have to be in three-dimensional space.” She quoted a Facebook post by resident playwright Andrew Hinderaker: “I wonder if I’ll ever again write a play that can be developed through music-stand readings.”

Even as recently as a decade ago, the approach was more homogenized than it is now, according to Cohen.

“The frame for a long time was, ‘If I’m not sitting at a hipster coffee shop and writing my play, and then getting it to X theatre company that’s hot Off-Broadway, then it lacks validity.’ I really see a desire from writers now to return to process.”

Hand in hand with that return to process comes a demand for flexibility, which play development centers are positioned to offer. Recently at the Playwrights’ Center, for instance, a writer asked to workshop a play over a four-week period, but with rehearsals only once or twice each week and rewriting in between. In another case, a writer might want to devise a piece over four intensive days, with actors and other collaborators in the room. Another writer might work best with a lighting or sound designer on hand to function as a sort of dramaturg.

“We try not to ask what writers need,” said Cohen, “and instead ask what they want. All artists get to that point where we’re like, ‘Okay, we can live off ramen and some rehearsal cubes.’ We want to ask, ‘If this is your fantasy dinner party, who would be in the room?’”

That could mean intentionally miscasting just to bring in different collaborators.

“Because we don’t have to worry about a production or selling tickets, we can help find people who give good process,” Morse said. “We can say, ‘This is such a great actor in a process. They can meet you where you are.’”

By choosing their own partners, writers gain more agency, and the ability to pay their collaborators in a residency setting contributes even more to that confidence and ownership. Morse quotes New Dramatists alum Karen Hartman as differentiating the play development centers as places where “playwrights are host artists, not guest artists.” Continuing that idea, Morse added, “Theatres want to promote that playwrights are part of a community, and they are in the broadest sense of the word, but playwrights are itinerant. They come in and go away. Here there’s an investment of seven years. That’s a lot of time.”

Indeed, time may be the most precious resource these development centers offer. With a seven-year residency, or even a three-year one, writers can let go of panic about running down the clock or wasting opportunities. There isn’t the sense that each reading that doesn’t move the play forward at a certain pace is time they won’t get back. “They can live in the questions longer,” said Morse.

“In a certain way, I think what we are trying to do at all the theatre labs is very, very old-fashioned,” Eisner mused. “It’s what education should be. It’s a return to Socratic thinking.”

Certainly many producing organizations do house important play development resources as well. Festivals and project-specific labs, such as those at the O’Neill Theater Center, Sundance Theatre Institute, PlayPenn, New Harmony, and others, continue to deepen the options for new-play development. But all of that opportunity can still ultimately feel like a test or audition. Producing entities—by their nature—are looking for plays to produce. “If you know you’ve got a reading coming up, you can do some development, but there’s that warning: ‘Don’t do too much, you’ll get a messy version in that reading, and the theatre won’t want to do it,’” said Cohen.

But taking the question of production out of the equation means a writer has the space to experiment, even to fail. “If there’s a difference at the new-play centers, it’s that they are autonomous,” said Eisner. “People used to complain about development hell. But to have a play lab that doesn’t have a production actually creates spaces where artists can do whatever they want, because they’re not worrying if I’m going to put them on the mainstage.”

The flip side of that, though, is that developing a play with a theatre that has committed to a production can also create a safe, organic work space, Cohen pointed out. The hat trick would be to combine the unfettered creative space of a play development center with the rock-solid assurance of a production. Because even as development labs have proven crucial in the process, plays are created to be produced, not developed.

Exchange between producing organizations and the development centers has in the past been tenuous, and Eisner called this “the No. 1 challenge in the industry today. Because we’re capitalistic, we understand how to grow our institutions. If I’m running a theatre and I want to develop plays, I don’t look outside my organization; I look to my own resources to add play development within my organization. We’re a society of whole institutions. We need to find ways to collaborate.”

Cohen, who admitted he was an odd choice to lead the Playwrights’ Center back in 2009 because he comes from the producing side of things, pitched just such a set of connective programs at the beginning of his tenure. Now the Center works with a cohort of about 100 theatres, called the Regulars, who share its affinity for artist-

first play development.

“We’re creating funding to fly in artistic leaders of partner theatres to spend time having meals, conversations with writers,” Cohen said. “They see readings, but really it’s to talk about art and process instead of play pitching.” The Playwrights’ Center has also co-developed work with some of the Regulars, serving as a neutral middleman and sharing costs of work to be produced by the theatres. “This benefits both a small theatre that doesn’t have development funds and a larger theatre where maybe it’s too restrictive for whatever reason to develop the play there,” said Cohen, pointing to a recent exchange with the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and a new work by Idris Goodwin.

The trial run of a similar co-development program at New Dramatists, called Full Stage USA and funded by the Mellon Foundation, concluded in 2014, but something comparable could find future life, Morse said. According to a final report on the program, penned by Morse and Srila Nayak, the initiative rose out of the expressed need by playwrights for more productions.

“There was widespread agreement that new-play development within producing theatres had become increasingly dead-end and that the choices of new work nationwide were becoming homogenized,” said Morse. “Furthermore, a growing divide existed between playwrights and artistic leaders or ‘gatekeepers.’ They disagreed on what made a play ‘finished’ or ‘ready.’ They lacked shared terminology for the goals of development.”

The collaborative nature of the Chicago theatre scene might pave the way for that kind of partnership at Chicago Dramatists, said Beals.

“Very often in Chicago we ‘share writers,’” she said. “Residents might be at the Hypocrites or the Goodman Playwrights Unit. How can we combine those resources and work within the system so that a reading at that company could be followed by a workshop with us? We want to position ourselves as a resource to the city.”

As the leaders of these play development centers work to define and provide solutions for the needs of playwrights—as well as find the best ways to educate the theatre field—three big needs continue to stand out as the most pressing.

One: Playwrights still need more productions—first, second, third, and so on—but also space for different kinds of productions. “We need to have a greater variety of productions that are more reflective of who is writing,” confirmed Morse. “If you look at the bigger organizations, that’s a smaller representation of who is writing than what we see at New Dramatists, and I’m sure my colleagues would say this as well. We’re seeing a lot of kinds of work that’s never reaching the stages—not because it’s not good, but because of access, or because it’s beyond our dramaturgical vocabulary at this point.”

This extends both to the style and structure of plays being written and also to who is writing them. There remains a gap between the number of female writers, trans writers, or writers of color receiving development opportunities versus production opportunities, which still disproportionately go to white male cisgender writers.

Two: Playwrights need to be able to sustain a quality of life, from housing to health insurance to the ability to work a single job (or even just two). “We need playwrights to remain in the field beyond 30, after they’ve finally learned their craft,” said Eisner, “even if they also need to write for television to make a living.” The rise in playwrights working in television who still maintain identities as playwrights is a promising trend (and not just because television writing has gotten so much better). Morse sees this turn of events as a result of playwrights acting as stronger advocates for one another than in the past, hiring their colleagues when they are in a position to do so, so that there is an easier crossover between the television and theatre sectors.

Life-sustaining fellowships can make a significant impact in the career of a playwright, freeing up time and space to focus on craft. But even with all the opportunities offered by these play development centers and other sources, there are many more struggling playwrights than awards.

Three: Playwrights need to be seen as leaders and decision makers in the field. As Cohen put it, “What practices we develop at our respective organizations correlates a lot to how we can not only support writers with a particular project, but really think about how we can reframe playwrights as leaders in the process, so that they are thought of that way in the field.”

Eisner agreed: “If we weren’t a theatre company, we’d be a leadership institute.”

Sarah Hart is a former managing editor of this magazine. She lives in Asheville, N.C.

A version of this story appears in the October 2016 issue of American Theatre.