There’s a fine line between a revolutionary and a whiner. I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, so I looked up the definition for both words. Revolutionary: “a person who works for or engages in change, a hero.” Whiner: “a person who habitually complains or grumbles: complainer, crab, faultfinder.” Two words on opposite sides of the spectrum, and yet the line is oh so fine between the two.

This idea resonated with me one day after an exchange between myself and a work colleague. Like almost every theateremaker in the world, I work at a “money-making” job. Mine was at a restaurant in New York City. I was a pot stirrer, figuratively. I was employed as a busser, but I was good at stirring the pot. One day a server approached me and asked, “Why are you mad?” I responded with, “I’m mad? I didn’t know I was mad.” Again he asked, “You’re mad. Come on, why are you mad?” And I replied, “Why do you think I’m mad?” And he said, “You’re mad because you’re working for the Man.” I replied, “The Man?” And he said, “The slave master.” He was referring to upper management. He said, “Why are you stirring the pot? Stop trying to change everything. Stop complaining. Just make some money, pay your bills, and enjoy the benefits.”

I worked in “fine dining.” Elegance was key and sweating was distasteful. My job consisted of gracefully clearing the empty plateware of wealthy people who regularly have expensive dinners to discuss how to get richer and beat the world. Management would always say that our guests should feel like we aren’t even there. It sounds like an impossible task, but it’s incredibly easy when most of your guests are used to not seeing you.

Did I hate my job? Yes, but I didn’t hate my job because of the ridiculous financial gap between the guests and myself. I never really put much thought into that. I came from a respectable working-class family. At home we never spoke about money, mainly because we didn’t have any. No, I hated the job because it operated under a system that felt familiar. It felt like my country. Just as the United States is divided between upper, middle, and lower classes, restaurants are divided by management, front of house, and back of house. Managers are at the top, followed by front of house: servers, bartenders, and hostess. Just below that we have the back of house: bussers and cooks.

And at the very bottom we have Mamadoue, the African dishwasher.

My journey to Mamadoue, one of the central characters of my new play The Parlour, began with Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, continued through the wedding of my close friend and mentor, playwright Lucy Thurber, and now culminates in a reading with MCC Theater (one night only, Sept. 19).

I read The Alchemist in high school and something changed. It was like my heart and brain shook hands for the first time. I was ready to pursue my “personal legend.” At the time I secretly wanted to be an actor. It was secret because where I grew up, in the Bronx, success looked more like being an athlete or a rapper. If you wanted to do something else, there was something wrong with you. There weren’t any real opportunities in our borough. The Bronx was a stagnant pond next door to an energetic river full of life and force. But I wanted to be an actor. I joined the drama department as a senior in high school, and my first experience was acting in a play called Journey. None of us knew what we were doing, but we opened the show anyway. If there is one thing the Bronx is excellent at, it’s breeding fighters.

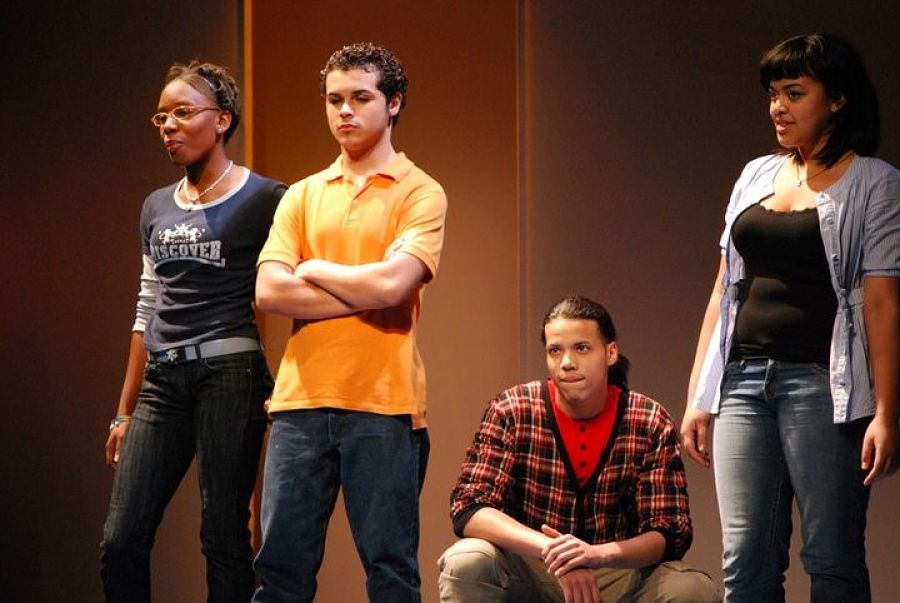

A couple days later my guidance counselor came across a free after-school acting and playwriting program that was holding auditions for New York City kids from all five boroughs. This was MCC’s Youth Company. It was probably the most diverse room I’d ever been in at that point in my life. There were kids of every color, size, gender, sexuality, and economic background. I wanted to be a part of the Youth Company so badly, I was smiling for two hours straight—and I really hate my smile. The couple of days after the auditions were the longest days of my teenage life. Long story short, through a series of misunderstandings that brings to mind a line from The Alchemist, “When you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you achieve it,” my smile and I joined the program.

It was at MCC that I met my mentor Lucy Thurber, who leads the Playwriting Lab for the Youth Company. Lucy by far is one of the most authentic human beings I will ever meet in my life. She taught me the power of speaking truth, not only in my work but to myself. More importantly, Lucy taught me how to be a good friend by just loving people for whom they are. Last May I had the pleasure of walking her mother down the aisle for Lucy’s wedding to Jenna Worsham. Playwright Adam Bock officiated, and gave a sort of sermon in which he said that our job as playwrights is to look out into the world until we find something we see unfit and say, “Wait a minute…” We tell stories to create change.

Which brings me back to Mamadoue. I started writing The Parlour during my early career writers group at Clubbed Thumb, and am continuing to develop it with MCC’s PlayLabs program, where I’m working with their artistic staff, a director, actors, and a public audience to further develop the piece. The Parlour is an ensemble comedy set behind the scenes of an upscale restaurant—sound familiar—where a racially and socioeconomically diverse cast of characters struggles to survive the high-stakes world of Manhattan’s fine dining industry. My inspiration for the play came two years after that why-are-you-mad exchange with a server at my first restaurant job. I started to think: Why was everyone in the back of house black or Latino? I found myself wondering how it is possible that a couple of twentysomethings in the front of house can make three times the wage of a person like Mamadoue, who works longer hours, a harder job, and has a family to support. I’m not arguing that servers don’t work hard; I know plenty of servers who bust every bone in their bodies to provide the best possible service for their guests.

I had an interesting conversation with a friend about this subject recently; we both agreed that front-of-house and back-of-house employees work hard. The difference is that folks in the back of house work hard physically. And why are we devaluing the physical? In my five years working hospitality, I’ve been a server, a busser, a food runner, and a barback. At every job it’s always the same: For all of us in the front of house, there are Mamadoues in the back, disempowered by the system.

We all know who Mamadoue is. If you’ve ever worked in hospitality and don’t know Mamadoue, then you might be a part of the problem. Actually, if you ever had a job, especially one that emphasizes coming together as a team to achieve a common goal, then you too should know Mamadoue. Mamadoue exists! He is real! He works retail, construction, manufacturing—the list goes on. The Parlour is my way of seeing something unfit and saying, “Wait a minute…” My hope is that if enough of us do this—choose to tell stories aimed at creating change—we might just help make some.

Does that make me a revolutionary or a whiner? I don’t know, but I’d like to think I’m on the right track.