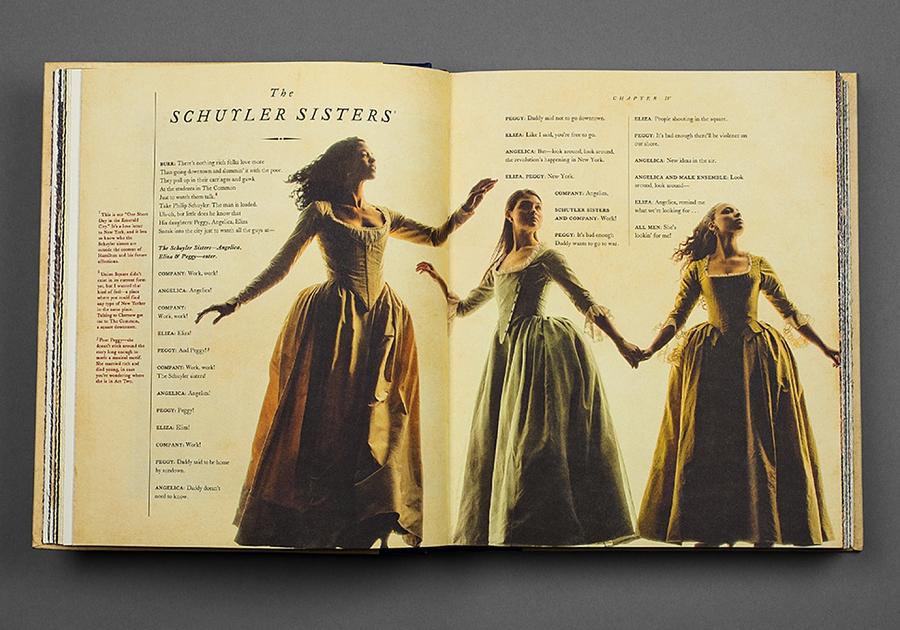

What accounts for the phenomenal success of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton? Four new books offer some clues. Only one of them focuses on the show exclusively: Hamilton: The Revolution includes the complete libretto, annotated by Miranda, alternating with chapters by former critic and Public Theater staff member Jeremy McCarter chronicling the six years it took to make the musical about the “10-dollar Founding Father without a father.”

This official Hamilton book is not shy about proclaiming the show’s greatness. McCarter declares that the “widely acclaimed musical…doesn’t just dramatize [Alexander] Hamilton’s revolution. It continues it.”

Such over-the-top assessments are commonplace these days. First Lady Michelle Obama has called it “the best piece of art in any form that I have ever seen in my life.” The new books are equally enthusiastic.

“Hamilton is the best show I have ever seen,” writes Drew Hodges in On Broadway: From Rent to Revolution (the “revolution” in the title referring to Miranda’s musical), which is essentially a coffee table book about theatrical advertising campaigns conducted by Hodges’s firm, SpotCo.

Hamilton has “created a palpable excitement,” writes Jack Viertel, the author of The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows Are Built. The musical Hamilton has “implicitly raised questions…about burning American issues…It also provided a fascinating discovery that should have been obvious: Rap is a great way to tell a theatrical story.”

A key secret to Hamilton’s success, if you believe Viertel—and he’s persuasive—is, paradoxically, that the show is a “revolution” that follows as much as departs from the model of the classic American musical.

Theatre-lawyer-turned-producer John Breglio suggests the same in his book I Wanna Be a Producer: “Hamilton displays an ingenious melding of rap, pop, and classic musical genres into a seamless whole.”

The volumes by Hodges and Viertel devote only a few pages to Miranda’s watershed hit. Breglio’s book merely mentions it half a dozen times as one of a string of examples. But all place the show fully within the context of their implicit or explicit message: American musicals matter.

In The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows Are Built, Viertel offers lessons in the craft derived from a course he developed at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. The book focuses on the structure of successful musicals, going chronologically step by step from the overture to the finale. But underneath the rulebook, he is making three arguments about the American musical:

- To quote him: “If Shakespeare is England’s national theatre, aren’t Broadway musicals ours?”

- The best American musicals explore what it means to be, or become, an American. So Hamilton’s concern with contemporary issues, Viertel writes, is “a direct descendant of Oklahoma!”

- Yes, Viertel believes, the Golden Age of American musicals ended half a century ago, and his book is threaded with analyses of such exemplars of the era as Oklahoma!, Gypsy, and Guys and Dolls.

The best musicals since then, he argues—from Hairspray to The Book of Mormon—more or less hew to the same template. If good musical theatre writers are constantly trying to break the mold, what they produce ultimately still uses it. Hamilton is no exception. “Clearly more influenced by Les Misérables than by Rodgers and Hammerstein, it nonetheless follows the American rules in a number of fascinating ways, and always to its advantage.”

Viertel describes those rules in exquisite detail, illustrating each with many examples. Opening numbers establish what the musical is going to be about and set the tone. He recapitulates the famous story of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, which was bombing in out-of-town tryouts because the original opening, “Love Is in the Air,” promised charm while the musical delivered mayhem. The new opening number “Comedy Tonight” fixed the problem, and the show landed.

Likewise Hamilton’s opening number “sets the style, the tone (unique as it is) and the point of view of the show perfectly (complete with the information that the hero will be dead at the final blackout).”

The opening number often leads directly to the “I Want” song. “The hero has to want something that’s hard to get, and go after it come what may. The sooner the audience understands this the better.” Classic examples are “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” from My Fair Lady and “Some People” from Gypsy. Hamilton’s, of course, is “My Shot,” which Viertel calls “a distant but recognizable descendant” of West Side Story’s “Something’s Coming.”

There are several more steps he details (such as “the conditional love song,” as in, “If I Loved You” from Carousel) until Viertel comes to what he calls the “tent pole”: the song near the end of Act I that “keep[s] the roof from caving in on the audience,” giving theatregoers a shot of energy so they’ll stay attentive until intermission. These are usually fun numbers, such as the Havana sequence in Guys and Dolls, the “Motherhood March” in Hello, Dolly!, and “Pick-a-Little, Talk-a-Little” in The Music Man. The tent pole in Hamilton is “the entire American revolution”—two songs back to back, “History Has Its Eyes on You” and “Yorktown.” It’s not a fun song per se, but “the kinetic excitement of watching a real showman figure out how to do a war in one extended number manages to thrill and reignite an audience that has already been sitting for a long time and processed a surprisingly large number of events.”

Second acts are famously harder to pin down; accordingly, Viertel’s analysis of them in the last third of the book can be confusing. It is unclear, for instance, how the “11 o’clock number,” a term he seems to dislike, differs from what he labels the “main event.”

But whether one accepts every rule in Viertel’s exegesis of American musical architecture, his book is invaluable in its summaries and discussions of specific shows we might not know (or not remember well) but should. He even illustrates the plot of Guys and Dolls with a chart. And he includes a final chapter with his recommendations for the best recordings of the 37 musicals he has analyzed, and for 20 more musicals “that can’t be ignored even though they are not quoted in the book.” A storyteller as much as an analyst, he leaves room for a little whimsy, though he restricts personal anecdotes largely to the chapter titled “Intermission,” where we learn the most about his background: A former critic and dramaturg, he is now both an executive at Jujamcyn Theaters (owners of five Broadway houses) and the artistic director of New York City Center Encores! That 22-year-old annual series does concert versions of old American musicals, many of which initially flopped, with the aim of winning new respect for them. Jack Viertel’s book effectively does much the same for the American musical as a whole.

Like Viertel’s book, John Breglio’s is organized chronologically. Intended as a nuts-and-bolts primer for theatrical producers, it does itself a disservice by slapping on a desperate-to-be-catchy title: I Wanna Be a Producer: How to Make a Killing on Broadway…or Get Killed. Its 29 chapters range from coming up with the idea for the play or musical (“The idea doesn’t necessarily have to originate with you, the producer…But it’s your job as the producer to make it come alive”) to organizing the opening-night party (“Don’t hire an amateur to organize the party…Don’t make a speech”). There are extensive technical discussions of royalty pools, the Authors’ Collaboration Agreement, the Approved Production Contract, and the like, as well as more readable chapters, such as one on advertising, marketing, and the press.

Breglio was a high-powered entertainment lawyer for decades, with clients including Stephen Sondheim, August Wilson, and Michael Bennett. Ten years ago, Breglio became a producer, beginning with the revival of A Chorus Line. His book is sprinkled with anecdotes from his practice and his experiences producing. The most interesting are those involving Bennett, who became his friend; Breglio now serves as executor of Bennett’s estate. But as former Breglio client Oskar Eustis of NYC’s Public Theater points out in the foreword, “This is not a gossipy book: John has too much class, and too much respect for his clients and friends, to write a tell-all memoir.” On the contrary, much of I Wanna Be a Producer reads like an attorney’s memorandum (“An underlying rights agreement can be broken down into 10 parts…”). The best way to look at this book may be much the way a premed student regards a course in organic chemistry: If you can make your way through it, maybe you really do belong in the profession.

Reading Breglio’s chapter on the increasingly common collaboration between not-for-profit and commercial theatres inspires a thought about Hamilton’s success that is nowhere in the author’s actual text. Breglio dates the beginning of this “uneasy alliance” between commercial and non-commercial theatre to A Chorus Line, which had its initial run at the nonprofit Public Theater and transferred to Broadway in 1975, where it became a phenomenal success, generating millions of dollars for the Public—not unlike Hamilton, which also began at the Public. Though Breglio focuses on the legal and financial ramifications of such arrangements, one senses the clear-cut artistic advantage in being developed at not-for-profits, whose “mission and purpose,” Breglio points out, “have more to do with the advancement of the arts than increasing a revenue stream.”

It wouldn’t be inaccurate to describe On Broadway as somewhere between a vanity publication and an elaborate business card. It offers a look at the advertising campaigns of 90 productions over the 20-year history of advertising firm SpotCo. But it is so well designed that it’s a fun coffee table book, and the short accompanying texts are by a clever selection of Who’s Who in Broadway—and beyond. David Sedaris writes the foreword because, before he became a famous writer, he cleaned offices, including SpotCo’s.

It’s interesting to see pieces by Hamilton’s lead producer Jeffrey Seller, who has been a client of SpotCo for 20 years, starting with Rent. He describes Hodges as “a tall Chelsea hipster with the nerdy glasses and a plaid shirt.” Seller also writes about his work with SpotCo on other shows he has produced, Avenue Q and In the Heights, but the hipster remark seems the most telling. What Hamilton has in common with Rent and Avenue Q is “downtown” sensibility whose very coolness was a selling point for uptown.

At the client meeting for Hamilton, Miranda writes, he told the SpotCo designers he didn’t want any artwork featuring the founding fathers in gold chains “or any other hackneyed hip-hop trope that people who have no idea about hip-hop think hip-hop is.” SpotCo’s Nicky Lindeman explains that the show’s now familiar logo uses the star from the American flag. “The black star and the black silhouette were a nod to portraits of the period, but merged together they seemed like a modern image”—which feels like an apt metaphor for the show itself.

Hamilton: The Revolution bolsters the observations about Hamilton the musical from the other books. It should thrill serious students of musical theatre, whether or not they are matriculated.

This is not to say that it is anything close to a scholarly tome; there is not even an index. It’s a book for fans. There are page after page of full-color photographs from the production (many of which form the backdrop for the complete lyrics). As part of the narrative, McCarter profiles members of the cast, the creative team, and others connected to the show, occasionally dipping into the gushing tone of fanzine features.

Still, if Hamilton: The Revolution is a souvenir book, it’s one that—like the musical and its creators—is unusually ambitious. Even many of the personal stories go beyond the usual fanfare. Alex Lacamoire, the show’s music director, orchestrator, and arranger, is hard of hearing, a disability he says may have actually aided his musical career: “Maybe I’m more attuned to certain things.” There is an especially heartbreaking passage about the song “It’s Quiet Uptown,” which occurs in the show after Hamilton’s son Philip dies in a duel. “Andy [Blankenbuehler] couldn’t bear to choreograph it, not with his daughter, Sofia, fighting cancer…” Then, just before the cast was to sing the song for the first time at rehearsal, Oskar Eustis’s 16-year-old son died. Eustis and his wife wound up listening to the song every day during their first week of mourning.

Meticulously designed to evoke the show’s 18th-century setting, the book uses the kind of dull parchment-like paper and elaborate chapter titles one associates with the era. The book’s frontispiece offers the subtitle: “Being the Complete Libretto of the Broadway Musical, With a True Account of Its Creation. And Concise Remarks on Hip-Hop, the Power of Stories, and the New America.”

McCarter’s chapters flesh out the now-familiar narrative of the show’s creation, from its beginning on May 12, 2009, with Miranda’s performance of the musical’s first (and at the time only existing) rap at the White House before President Obama.

But the book is steeped not just in the show’s history, but in U.S. history and in the history of the American musical.

“The four grandparents of the show,” McCarter quotes director Tommy Kail as saying, “are Sweeney Todd, Jesus Christ Superstar, Evita, and Gypsy.”

Miranda’s copious annotations of the libretto demonstrate the extent to which the show employs the traditions and conventions of the musical form. In the second footnote (printed vertically along the margin) on the very first page of the libretto, he explains that the opening number of Hamilton—initially conceived as a monologue for Aaron Burr—“owes a debt to the prologue of Sweeney Todd: All our characters set the stage for our main man’s entrance.”

And in the following chapter, McCarter writes, “‘My Shot’ is, in the lingo of musical theatre, an ‘I want’ song…Without a song like this, you wouldn’t get very far in a musical: A character needs to want something pretty badly to sing about it for two and a half hours.” He then adds something intriguing: “And you wouldn’t get anywhere at all in hip-hop. For all of its variety of style and subject, rap is, at bottom, the music of ambition.” Here then is another reason that rap in a musical works so well.

“My Shot,” Miranda makes clear in his notes on the song, is influenced as much by South Pacific as by rappers Tupac Shakur, Mobb Deep, Big Pun, and Notorious B.I.G. It’s fascinating throughout to parse Miranda’s omnivorous influences—not only rap and Broadway but also Harry Potter; the Beatles; TV series like “The West Wing,” “My So-Called Life,” and “Parks and Recreation”; Macbeth; American history (his lyrics at times embed verbatim quotes from various Founding Fathers); Gilbert and Sullivan (“My first part in high school was as the Pirate King in The Pirates of Penzance,” he shares in an annotation for George Washington’s song “Right Hand Man”); and his own life (“I see myself, almost painfully, in every character onstage”).

The book also addresses with little ado one aspect of the production that has generated the most commentary: the casting of people of color in the roles of white historical figures. These particular performers, McCarter says, were “best able to perform the songs that Lin had been writing…Lin and Tommy saw no difficulty in making this imaginative leap. In fact, they raised it to a principle. As Tommy would state it again and again in the years that followed: ‘This is a story about America then, told by America now.’”

Hamilton: The Revolution might be most useful in helping us figure out the musical’s appeal by supplying the lyrics of this sung-through show, with the songwriter’s annotations describing the inspirations, explaining the meanings, and generally directing our attention along the way. When Renée Elise Goldsberry, as Alexander Hamilton’s sister-in-law Angelica Schuyler, sings “Satisfied” onstage, audiences are typically impressed with the speed and ease with which she delivers some complex rhythms. But in reading along with the lyrics, one can grasp more fully how theatrical this song is: Framed by Angelica’s wedding toast at the marriage between Hamilton and her sister Eliza, it rewinds in time to show the alchemical first encounter between Angelica and Hamilton, then his first meeting with Angelica’s sister Eliza, which provokes Angelica’s arguments with herself about why she should give him up for her sister’s sake. “This is the most ambitious tune in this show,” Miranda writes in another note, and then adds in parentheses, “and that’s saying a lot.” One might be taken aback for a moment at what sounds like an unseemly boast. But it’s hard not to agree.

New York City-based arts writer Jonathan Mandell is a frequent contributor to this magazine.