Jen Silverman always thought she would become a novelist. And you can’t blame her: Silverman’s life is one that lends itself well to travelogues and memoirs of self-discovery in exotic locations. She grew up, literally, all over the world. “I think I was 15 months old when we moved to Japan,” she recalls. She was born in Simsbury, Conn., the child of a physicist and chemist. “We were in and out of Japan two times in my childhood, in and out of France four to five times…” By the time she was 13, she had also lived in Finland, Sweden, Italy, New Zealand, and Canada. She moved to Japan again after undergrad. And she speaks four languages.

It’s this nomadic existence—the continuing process of asking questions and learning about every new place she visited, every new person she met—that has influenced the way Silverman writes plays. “It’s the feeling of constantly being a little bit outside of it and being a little bit new to it,” Silverman explained over a cup of tea at New Dramatists in New York City. “I just ask questions a lot and nobody answers them for me, so I explore them in plays and still don’t have any answers.”

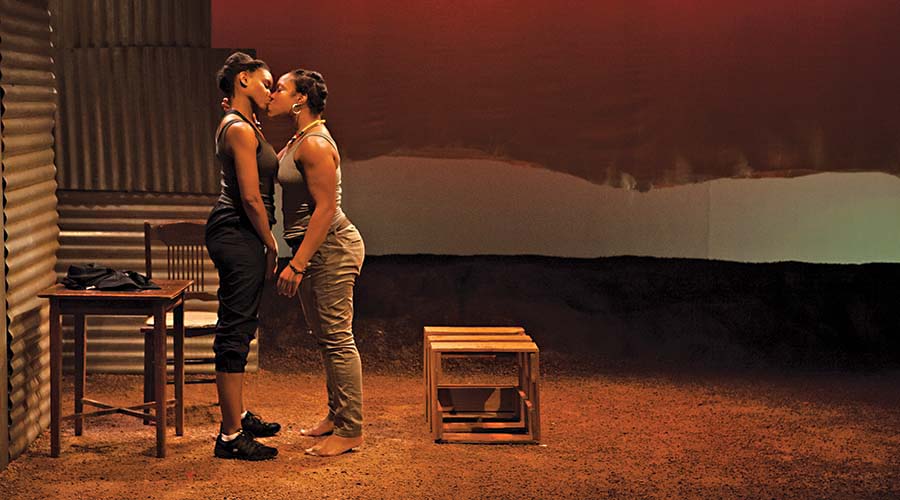

To use a familiar traveling metaphor, it’s about the journey, not the destination. And in Silverman’s plays, what journeys they are. Much as she has herself, Silverman’s plays span the entire world, from two white women going through a midlife crises in Iowa (The Roommate), to black queer women speaking up against rape in South Africa (The Dangerous House of Pretty Mbane), to a Japanese-American woman mourning her deceased brother in Tokyo (Crane Story), to four women finding their voice while living in Victorian England (The Moors).

If you aren’t familiar with Silverman’s work, that will change soon. The New York-based playwright has been produced locally since 2011, but it was The Roommate at the 2015 Humana Festival of New American Plays at Kentucky’s Actors Theatre of Louisville that put her on the larger national map. Productions at Yale Repertory Theatre (The Moors) and InterAct Theatre Company (The Dangerous House of Pretty Mbane) followed.

This season, Silverman is racking up her frequent-flier miles. The Roommate will be produced at Everyman Theatre in Baltimore (Oct. 26-Nov. 27), California’s South Coast Repertory (Jan. 3-22, 2017), and San Francisco Playhouse (May 23-July 1, 2017). Washington, D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company is producing the world premiere of Collective Rage: A Play in Five Boops (Sept. 12-Oct. 9); Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park will premiere All the Roads Home (March 25-April 23, 2017); and Off-Broadway’s Playwrights Realm is mounting The Moors (Feb. 27-March 25, 2017).

That’s not even counting the works Silverman has in development. On the day of our interview, Silverman was getting ready to leave for Berkeley Repertory Theatre, where she is developing My Father the Speeding Bullet: Nincest for the theatre’s Ground Floor program. It’s a play-with-songs about Anaïs Nin that features Pig Iron cofounder Dito van Reigersberg as the writer.

“She’s not a mainstream, American-realism kind of playwright,” says Howard Shalwitz, artistic director of Woolly Mammoth, who says he was moved to tears by Collective Rage when he read it. “Jen’s plays, every one of them, ask the audience to come into a somewhat odd world—to step over some sort of threshold that might be uncomfortable.”

Still, one might say that her current popularity is long overdue. Silverman has been listed on the Kilroys’ list of underproduced female playwrights for three years in a row, this year with two plays (Wink and Collective Rage). And she is the 2016-17 recipient of the prestigious Playwrights of New York (PoNY) Fellowship, which provides $100,000 worth of artistic support (including a free apartment for a year). The latter allowed her to quit her day job teaching.

In short, this is the year of Silverman. “She’s so goddamn prolific,” exclaims Kimberly Colburn, literary director at South Coast Rep, who has recommended Silverman for the Kilroys list twice. The two met last year when Colburn dramaturg’d The Roommate at Humana. “In all of her work, she’s got something to say; she’s not writing for the sake of writing. I think that might be the defining facet of her writing: It feels like she is the origin point. She finds a point of inspiration, or a new way of looking at the world, and chooses to harness that by writing about it in a play.”

Silverman wasn’t a theatre kid growing up, but she knew from an early age, while going through her parents’ extensive library, that she was going to be a storyteller. Her reading list included The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck, Giants in the Earth by Ole Edvart Rølvaag, and The Kalevala, the Finnish epic poem by Elias Lönnrot. “My parents just let me read whatever the hell I wanted,” she recalls. “I read Lolita when I was 10, 11, 12—somewhere in that range.” She adds with a giggle, “People are horrified by this.”

Silverman majored in comparative literature at Brown University, and that’s when she saw her first play and started taking playwriting classes, including one with Paula Vogel in her senior year. She also avidly consumed plays by female writers—Caryl Churchill, Naomi Iizuka, Naomi Wallace, and most important, Sarah Kane. She didn’t pay attention to the male canon until later (“I didn’t read an Ibsen play until grad school” at Iowa Writers’ Workshop).

“My early exposure to theatre was almost entirely female writers,” she explains. “I didn’t have the feeling of, ‘Is there a seat at the table for me?’ In my mind there was this table full of super-bold, outrageous, strong, political women. I looked at them and I was like, ‘Oh! Yes, please! Me too! I want to talk!’”

She hasn’t lost that fearlessness. Though the writer is short and petite, with a heart-shaped face, her pixie cut is buzzed on both sides, and she’s got a tattoo on each arm. And she’s possessed of a probing intelligence that can quickly detect bullshit.

“As someone who looks younger than I am, as a queer woman, I am aware that there is a certain way in which, often, men perceive me before they have read the work,” she says. “I have watched men talk to me one way and then read and encounter my work, and talk to me differently after that.”

They underestimate her? “Absolutely,” she says. “I think that young men are seen as being very promising, and potentially the next big thing. And young women are seen as a little bit naïve and they’ve got a long way to go.” That is also why she declined to state her age for this article.

How women are perceived is what led Silverman to write Collective Rage: A Play in Five Boops. (The full title might give you some insight into Silverman’s ambitious aesthetic, not to mention her sense of humor: Collective Rage: A Play in 5 Boops; In Essence, a Queer and Occasionally Hazardous Exploration; Do You Remember When You Were in Middle School and You Read About Shackleton and How He Explored the Arctic?; Imagine the Arctic as a Pussy and It’s Sort of Like That.)

The play imagines five different Betty Boops coming together to discuss their vaginas while staging Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. And they don’t all look like the hypersexual, coquettish Boop of pin-up fame; there are also Boops who are butch lesbians and Boops who are multiethnic.

Silverman wrote the first draft within a week, not because she expected it would be produced but because she felt driven to respond to being constantly catcalled on New York City streets, and more broadly to the idea of socialization—the conditioning that teaches women to be beautiful, kind, and apologetic, not loud and angry.

“Women can push back to this degree, but no further,” she explains, putting her hand up in a “stop” sign. “Once it gets too aggressive, it’s not pretty anymore, so stop. I really wanted to write a play in which the women were allowed to have an unapologetic conversation about, Who are we, versus who are we being told that we are, versus who do we want to be?”

For Silverman, Collective Rage was a way to tap into “the energy that happens when you get these women who are really questioning and overturning in the same space together. The energy builds on itself and feeds itself in a way I think is really dangerous.” She then slyly adds, “And to me, really sexy.”

It’s not Silverman’s only unapologetically feminist play. All the Roads Home, The Moors, and The Roommate all explore themes of women pushing against limitations placed upon them. Silverman wrote The Roommate to address the lack of roles for middle-aged actresses, and it accordingly shows how the 50s can be as sexy and fruitful for a woman as any time in her life. In a cultural conversation in which strong female characters are still controversial (see the backlash against the Ghostbusters reboot) and Beyoncé’s Lemonade is considered groundbreaking for its portrayal of female anger, Silverman is keeping her fingers on the pulse of that conversation.

“I am really interested in narratives for both queer characters and female characters that are way more complicated and way more authentic than the real estate that’s usually given to us,” says Silverman. “I feel like queer characters are permitted to come out, as long as they take the whole play to do it and feel conflicted about it. And women are allowed to be onstage as long as they’re talking about their husband. I’m interested in the territories that these exceptions are taking up and being part of that conversation. And that to me feels personally and politically and artistically important.”

For frequent collaborator Mike Donahue, Silverman’s work claims even bigger territory. “She’s very interested in power structures, and in class, and in hierarchy,” says Donahue, who directed her Phoebe in Winter at Off-Off-Broadway’s Clubbed Thumb in 2013, as well as the world premiere of The Roommate; he’ll also helm Collective Rage at Woolly Mammoth and The Moors at the Playwrights Realm. “She’s very interested in gender and performance of gender—the boxes we get put in and how we become aware of those boxes. She’s fundamentally interested in transformation and in the ability of people to powerfully transform themselves.”

In her spare time Silverman doodles—in particular, she draws suicidal penguins and pandas eating glue or carrying dynamite; she posts her work on Instagram under This Panda Is Sad. Though these characters haven’t appeared in any of her plays (yet), this side project isn’t that surprising. It’s an apt metaphor for Silverman’s plays, which aren’t just feminist; they subvert expectations.

Just take The Moors, which opens up in the style of a Brontë novel, with a governess showing up at an English manor, expecting to find her Mr. Rochester. Instead, it’s a house of women and she falls for the lady of the house, giving this Victorian setting a queer edge. The play also features a talking dog and moor hen.

And Silverman won’t write the same play twice. While The Roommate is what Silverman calls “naturalism on speed,” Collective Rage takes place in a cartoonish world of multiple Betty Boops, and Phoebe in Winter opens up in a living room that gradually becomes a literal war zone (think Sarah Kane’s Blasted but funny). But don’t expect her to write any of the following: an autobiographical play, a naturalistic play, or a play about a queer kid coming out.

“It’s really important for me to try to do something different with every play,” she says. “When I’m writing a new play, if I find that I’m retreading territory too easily, I’ll just throw it out and I’ll start over.”

If she’s allergic to repeating herself, she’s also intent on not boring her audience. As Adam Greenfield, associate artistic director of New York’s Playwrights Horizons, puts it, “I think that her interest veers toward these large-scale, epic, fabulous stories that tend to be episodic rather than climactic,” he says. Greenfield has directed workshop presentations of All the Roads Home and Angel Bones. “She wants to tell us a good yarn and fill the stage and have it be big enough to warrant it being on a stage. I love that her plays feel like they’re bursting at the seams; there’s such an explosive energy.”

Explosive is right: Even though Silverman has already written more plays than can be mentioned in one article, she’s just getting started. After all, she’s lived multiple lives and has a world’s worth of stories to tell. There are more journeys to take, more questions to ask, and more theatrical spaces to explode. She just turned in a theatre-for-young-audiences commission for InterAct Theatre, but it sounds very Jen Silverman: It’s a riff on Ubu Roi that features Hillary Clinton. Because who says a children’s show can’t be political?

“Right now, I’m really interested in just destroying everything,” Silverman concludes. “I think it’s so fucking useful for us as humans to undergo the practice of thinking we know what something is, and then watching that thing be deconstructed in such a way that we no longer can make the assumptions we were making. I think it’s useful for us to do that in theatre, where it’s safe.”