In the late 2000s, Evelina Fernandez began to write a play about an intergenerational Mexican-American family in Los Angeles, dealing with the loss of a son in Iraq, with the death of the beloved Pope John Paul II, and with assorted other challenges big and small. At the time she had no intention of joining the ranks of the epic durational play à la Angels in America or The Kentucky Cycle.

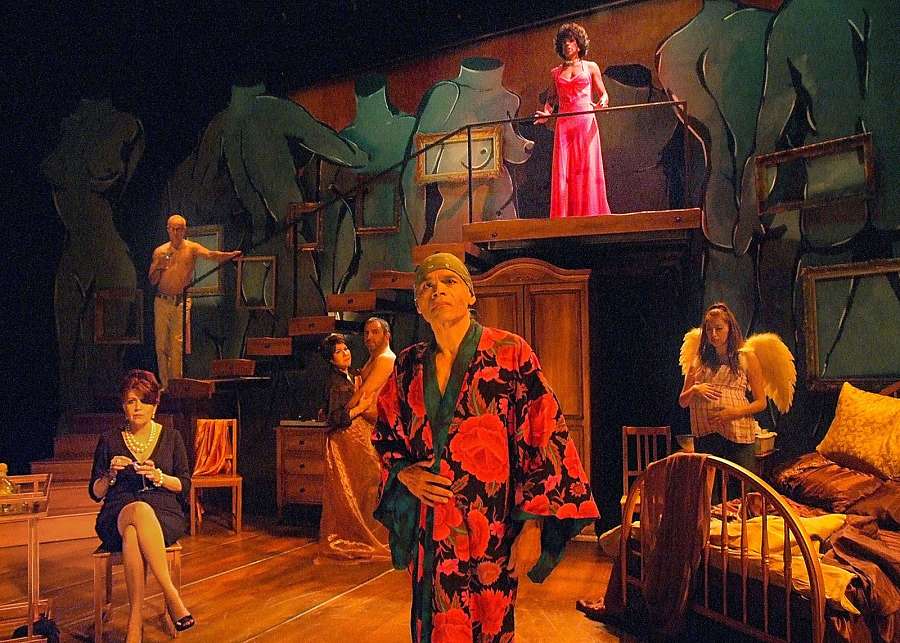

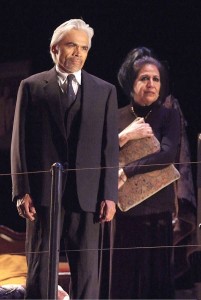

But she soon realized that there was more drama to be mined from the history of the fictional Morales family, which was loosely inspired by her own background. Soon a trilogy of plays took shape, and each part in the trio—Faith, Hope, and Charity—got staged in turn by the Latino Theater Company, which Fernandez runs with her husband, director José Luis Valenzuela, at the Los Angeles Theatre Center.

Now all three are being staged together as A Mexican Trilogy at LATC, Sept. 8-Oct. 9, in an ambitious undertaking that represents a kind of culmination for the nearly 30-year-old company. We spoke to Fernandez from the midst of rehearsals (and the inevitable rewrites).

Three plays at once is a pretty big undertaking, right?

I know, it’s huge—it’s too much. We’re in rehearsal right now, and I’m realizing: My God, it’s massive. But it’s exciting. I don’t think anything has been done like this, following Mexican-American history through multiple generations.

Eduardo Machado did his epic saga about Cuba and Cuban Americans, Floating Island Plays, back in the 1990s, but I think you’re right about the Mexican-American experience. Though now that I think of it, you were also in the movie American Me. Speaking of which, are you acting in this trilogy too?

I am. We’re a theatre company, so we all wear lots of hats. Originally I was not in Part 2 when we first staged it, but it was too hard to sit out there and watch—I hate being in the audience. I was like, “Get me back on the stage!”

Did you initially conceive this as a trilogy?

I wrote Part 3, Charity, first, and then I thought: There is more to say, not just by me personally but on the part of our company. It was a time—and it continues to this day—where we were hearing lot of anti-immigrant rhetoric. We get so frustrated, because there’s no acknowledgement of the long history of Latinos. We’ve been here for many generations, but we’re always portrayed as people who want to cross the border. So I thought, let’s do our part here and tell this story that hasn’t been told in its entirety. We take this family all the way from fleeing the Mexican Revolution to losing their son in the Iraq War.

So you started with the third play and flashed back?

Actually we began in 2011 with Hope, the second part. When we did readings, the 1960s story really resonated with our audience, so we decided to do that play first because it was in better shape. Then we did Faith, the first one, then Charity, the third. It’s kind of like Star Wars—everything was done out of order.

Are you doing the usual multi-night and marathon options?

Yeah, we’re doing it both ways: You can come on Thursday and see Part A, on Friday see Part B, or you can come on Saturday and Sunday and see the whole thing with a dinner break.

But wait—it’s three plays…

We split the middle play in half; it was the only way we could do it. People can’t come more than two nights. If you only see Part A, you end at the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Did you have models in mind as you worked: Kushner, Robert Schenkkan, even August Wilson?

I can’t really say that I did. I wrote the three plays never thinking that we were going to do them all together. When we decided we were, we started to figure it out. But I’ve seen durational theatre; I sat through The Iceman Cometh with Jason Robards when I was 9 months pregnant. I certainly remember that! And we saw GATZ at REDCAT and just loved the whole experience. But our audiences so rarely get to experience something like this—I’m specifically talking about the Latino audience. Some of our board members were actually worried, like, “Do you think anyone will want to do this?” Interestingly, we haven’t sold many one-nighters; more people have bought the whole-day experience. Everyone’s interested in seeing the whole story in one big sweep.

I’m sorry to say I don’t know a lot about your background before the Latino Theater Company.

I’m from East L.A. I got involved with the Chicano movement, and my first professional theatre credit was in Zoot Suit. Luis Valdez basically took me and put me on the stage without any real formal training; I think he was taken by my authenticity. So I found myself as a female lead at the Mark Taper Forum at a young age, and that changed my life. I always thank Luis for giving me that opportunity and pointing me in a whole new direction.

I know Chicano and Latino theatre from roughly the late ’80s on, and I know a bit about El Teatro Campesino. What was Chicano theatre in L.A. like before that?

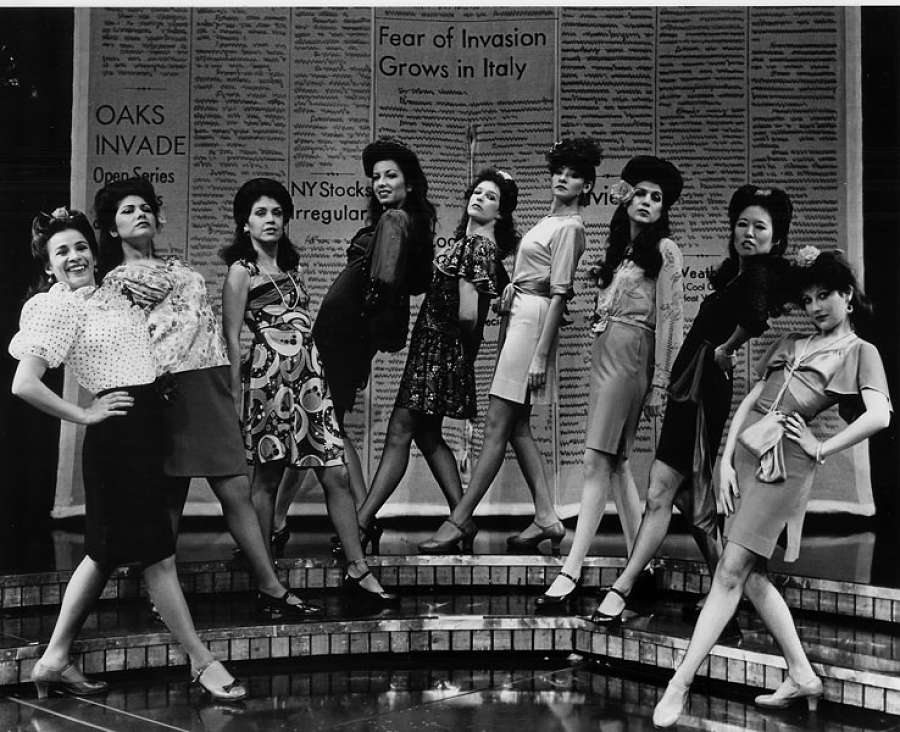

There was a big Chicano movement that grew out of the Civil Rights movement. During the Vietnam War there was a disproportionate number of Chicanos and African Americans being killed in Vietnam. There was a rise in protests against the war and against police brutality, and in favor of bilingual education and our history being taught in the schools. And because of El Teatro Campesino, there was a swell of Chicano theatres in the Southwest and even the Midwest. We used to have theatre festivals every year. There were maestros who came from Mexico and Latin America to train us in different kinds of theatre, and from that came our training, which is based in collective creation.

El Teatro de la Esperanza was a troupe I was a member of with José Luis in Santa Barbara; we also toured with it throughout the country and Cuba. When José Luis left Santa Barbara we came back to L.A., and he got the job at the Los Angeles Theatre Center. Latino Theater Company was born there.

That was an extraordinary time; I was lucky to be there for some of it.

It was. There was the Latino lab, the Asian lab, the African-American lab. It was an extraordinary time for diversity. When LATC closed, we originally went to the Taper, but then eventually we came back to LATC, and now we run it. It’s been close to 30 years. It’s unique to have a group of actors who have worked together for so long.

It’s true, there aren’t many examples—Wooster Group or Steppenwolf come to mind, though in the latter case they’ve grown into a big regional theatre.

Right. We still consider ourselves independent; we run our own theatre and we create and produce our own work.

Your training was in collective creation, but obviously you’ve also made plays as a sole author too. Where does this trilogy fit on that continuum?

This trilogy is not as informed by our ensemble as some of our other pieces, like Solitude or Premeditation, which we developed together though workshops. With the trilogy, even though there’s always input from the ensemble, I went off and wrote the pieces then brought them in. But for example, when I wrote Dementia, I knew that Sal Lopez was going to play the lead. I know that Sal can sing and dance, I know he can speak English and Spanish; those are all the elements I have to work with when I’m creating a character for Sal. We have developed a style, a way of working together. It always includes movement, dance, singing. We joke that in all our shows we laugh, we cry, and we have tequila shots.

And we write for a certain audience. We know the stories that are important to them. We also push the envelope and open their minds to different points of view. When we did Dementia, not too many people were writing about a gay Latino dying of AIDS. And there we had the gay audience sitting with the harcore Chicano audience; bringing those two audiences together in the theatre was a great accomplishment for us.

I was intrigued that Part 1 and 2 have Arizona settings—Jerome and Phoenix, respectively—as that’s my home state.

My mom was born in Jerome, and Part 1 and 2 are loosely based on the history of my family. I was born in East L.A., then my father took us to Phoenix and I lived there for the first 9 years of my life, then we moved back to Los Angeles. Part 2 is based on a lot of my memories of living in Phoenix in a very dysfunctional Mexican-American family.

Phoenix is where I grew up, and I lived for a long time in L.A. My sense of the Latino cultures in each is that they’re quite different, even though both are predominantly Mexican-American.

Yeah, my relatives in Arizona are very different from my relatives in Los Angeles. Some of them are even Republicans in Arizona! I feel like it’s a slower development of social consciousness there—I’m just talking about my family, and just what I observed, but it develops and moves forward at a slower pace. L.A. is just so diverse in so many ways, not only culturally and ethnically; there are just so many different parts of the city, and the way people relate to each other is different.

Do you ever go back to Phoenix?

My childhood was not very pleasant. I always say of Phoenix, “Oh, it’s so hot—the heat is so heavy.” I just remember us not having much and having electricity turned off, and having to sleep outside under the weeping willow tree because it was too hot to sleep inside. So I have an aversion to Phoenix. But I do love Northern Arizona.

The Taper is bringing back Zoot Suit in its 2017 season. Are you looking forward to that?

Oh man, I’m so excited. It was such a big part of my life, and Luis was such a mentor to me. I heard somebody say, “Wow, I hope it’s successful,” and I said to them, “Are you kidding me?” I think it’s going to be a huge hit. It’s great that Luis is directing it again. When I was in Zoot Suit, I was expecting my son, Fidel. Now both my children are actors. Wouldn’t it be amazing if they could audition for that?

This is a variation on a question I once asked August Wilson as he neared the end of his Century Cycle: Having documented such a long time span, how does the overall picture look to you? Have things improved or gotten worse? Are you hopeful for the future?

In Part 3, the granddaughter of Esperanza from Part 1 has just lost her son in Iraq, and they’re dealing with that loss. These are people who’ve gone through the Chicano movement. And then a young man arrives from Mexico with the dream of making it in the U.S., and he comes full of hope and full of questions; he wonders, “Why is there such pessimism? This is the best country in the world!” They have a conversation about the war. Rudy, the father, says, “I don’t want my son to go to war; I don’t believe in war.” And the young immigrant says, “Don’t you love your country? Don’t you believe you have to fight for your country?” I do see hope. As long as we keep coming, there’s always hope in the future.

The other day, José Luis and I had this event in our home. We have a circle of friends who support our work; most are successful Mexican Americans, some are Guatemalans, Ecuadorians. Everybody has a story. We went around and each one of them told their story. I was so moved: Some said, “I’m first generation American,” or, “I was raised in a foster home,” “I was on welfare”—everybody had different backgrounds. But they were all very successful. I’m a high school dropout, and my children graduated from UCLA and NYU. So many times the focus in the media is on the negative things that happen in our community—the gangs, the poverty—and not on the success we’ve had in this country. I think that definitely outweighs the struggle, and the things we still have to overcome.

Last question. It’s called A Mexican Trilogy, but apart from a prologue in Part 1, it’s all set in the U.S. Can you tell me about the choice of the title?

I’ve gone back and forth on that so many times: Should it be A Mexican Trilogy or A Mexican American Trilogy? The full title is now A Mexican Trilogy: An American Story. It’s about claiming that ethnicity. This is the story of a people: You start with a people, and you end with the same people. They are Americans; they are also Mexicans.