After you play Vivienne Avery, you might need a drink. The lead character in Steve Yockey‘s play Blackberry Winter has almost every line and rarely leaves the stage, which would make playing her daunting enough. But then there’s her story: She wrestles not only with her mother’s dementia, but also with her own dark thoughts.

And oh yeah—she’s funny. And she has a wild imagination. And she can bake. She’s the kind of character that actors might wait their entire career to play.

Right now, only a handful of women know her firsthand. Blackberry Winter had seven productions last season as part of a rolling world premiere from the National New Play Network, and this season it will be seen at least three more times. (Next up is a November production from Theatre on the Square in Indianapolis.) And the actors who starred in these productions have formed a type of sorority, reaching out to each new performer as she debuts.

For proof, look to Steve Yockey’s Facebook page. When a new production opens, he typically touts it on his wall, tagging previous Viviennes and heralding the newest member in their ranks. In March of this year, he tagged Adrianne Krstansky before her first preview at New Repertory Theatre in Watertown, Mass., and he asked the play’s veterans to “welcome her into [their] support group.”

They did. April Fossen, who delivered her Vivienne at Salt Lake Acting Company, wrote to Krstansky within a few hours, as did Carolyn Cook (Atlanta’s Actors Express, in the play’s first production) and Amy Resnick (Sacramento’s Capital Stage Company).

This was just a few weeks after Resnick’s initiation. At the start of her production, Cook replied to Yockey’s Facebook post to tell her, “Looking at that picture I see Vivienne, 100 percent. You are in for a hell of a ride. My love and best wishes.”

Not all the encounters are virtual. In June, Cook traveled to D.C.’s Forum Theatre to catch Holly Twyford’s performance in person. This was the first time she’d seen another actress in the role, which she developed in workshops and which Yockey partly based on her own experiences with her ailing mother.

“I had put Vivienne’s skin on my body and given it my voice and my shape, but this time I was thrilled to see her become someone else’s,” Cook says. “Holly and I hung out in the lobby forever after and talked and got to know each other. I was just glad that we got to talk and laugh and enjoy each other’s company, and also talk about the play.”

As Twyford recalls: “It was an instant connection, especially because it was around something like Blackberry Winter. Vivienne was very special because it’s very personal to Carolyn, and the reason I did it, aside from Steve’s wonderful writing, was my personal experience with my dad. So Carolyn and I were sharing something much more special than you would in a lot of other roles.”

Granted, this is hardly the first time actors have communed over a shared character. Many repertory companies thrive when older actors bequeath knowledge to the younger generation, and people have been passing down anecdotes about playing Hamlet for hundreds of years.

But there’s something about multiple productions of a new play—about all those people playing the same, previously unknown role at roughly the same time—that invites a special sense of unity. Together these performers are establishing a cultural memory. They’re refining a perspective on a role that could influence future performers for years. No wonder so many of them delight in finding each other.

This is not to suggest, however, that the actors are telling each other how to perform. “I have not had any conversations where anyone has said, ‘Do it like this,'” Cook says. “It’s more a sisterhood than an advice group. It’s a sense of shared experience and a sense of sharing something that is profound that calls on you to be deeply vulnerable.”

Twyford had a similar experience more than a decade ago, when she starred as Evelyn in the D.C. premiere of Neil LaBute’s The Shape of Things. That character is notoriously controversial because of the way she manipulates a man in her life, but the actress was adamant about liking her. When she met Amy Redford, who had also played the role, she discovered a kindred spirit. “There was this huge relief and this huge weight off me that this person had also had to defend the complexities of this character,” Twyford says.

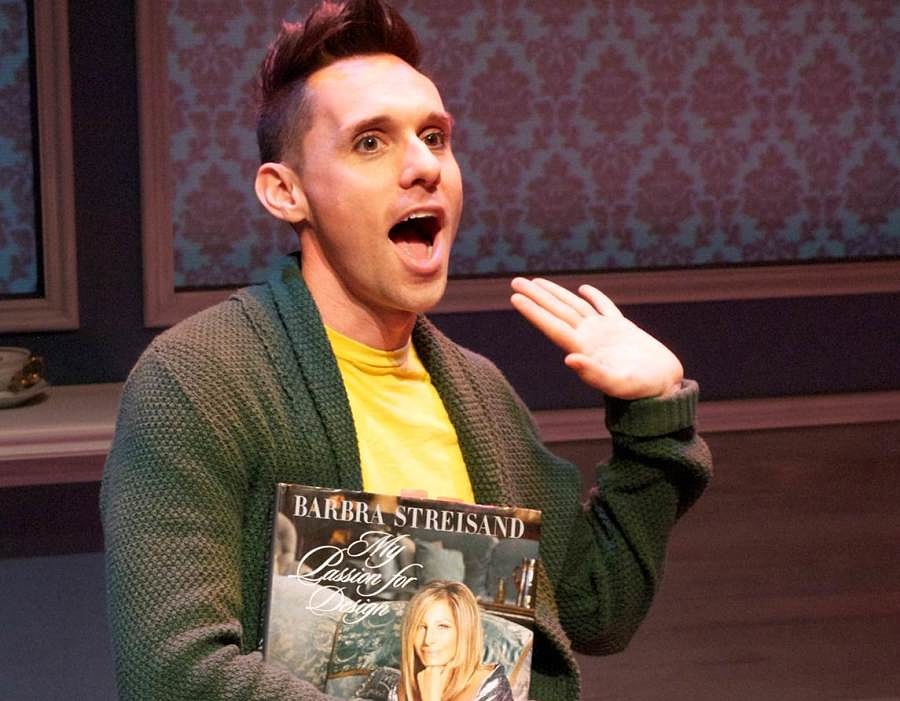

A shared empathy is also developing around Buyer and Cellar, Jonathan Tolins’s one-man comedy about Alex, a struggling actor who works in the shopping mall that Barbra Streisand installed under her house. Since it premiered at New York City’s Rattlestick Playwrights Theater in 2013, it has been produced all over the country, and many of the Alexes have stayed in touch.

That’s partially because they don’t have anyone else to talk to about performing the role. “The drawback of a one-man show is that it can be very lonely,” say Nick Cearley, who will play Alex for the fifth time when Buyer and Cellar opens at Pennsylvania’s Bucks County Playhouse this October. “So staying in touch with these other guys is almost therapy. They become the rest of your cast. I feel like it’s its own little Orpheum circuit, where we know everybody who has done the role of Alex in every production.”

Among other things, Cearley and his fellow Alexes have shared war stories about memorizing the chatty, detailed script, and they’ve traded tips on which references might not land. (Not everyone’s going to get a joke about Yentl, for instance, so it helps to be prepared.)

The Alex network also provides practical services. After Cearley had to drop out of a Buyer and Cellar production at Cape May Stage this October, he recommended Trey Gerrald, whom he knew had auditioned for the show in other places. Gerrald booked the gig—his first time getting the role—and he has since had what he calls “Alex dates” with Cearley.

“Nick and I have talked about what the piece is really trying to say and how he tackled certain parts of the material,” Gerrald says. “If we hadn’t been friends to begin with and he hadn’t had a hand in recommending me, I would probably feel this actor-y feeling of ‘I don’t want to cheat’ or ‘I don’t want someone else’s opinions to infiltrate my process.’ But Nick and I are different actors, so it’s going to be different anyway. And now it feels great to have this camaraderie and to know what he’s learned from doing it so many times.”

That camaraderie may very well endure, which is another reward from the culture around a new play. In the early ’90s, for instance, Cook and a good friend both played the same role in Lynda Barry’s comedy The Good Times Are Killing Me, and to this day they still say goodbye by quoting one of their character’s lines. “I still have that sense of sisterhood with her around that performance, and it’s been over 20 years,” Cook says. “There’s something very real about sharing that sense of privilege in taking a character from the stage and giving her life and breath and voice on stage.”