Though with their high wrongs I am struck to th’ quick,

Yet with my nobler reason ’gainst my fury

Do I take part. The rarer action is

In virtue than in vengeance.

—Prospero, The Tempest

In the early 1950s, an actor named Will Geer moved from West Nyack, N.Y., with his performer wife, Herta Ware, and their young family to Santa Monica, Calif. Helen Hayes had lived in West Nyack, as had John Houseman. They had been Geer’s world, and they—and he—had all moved west to work in films.

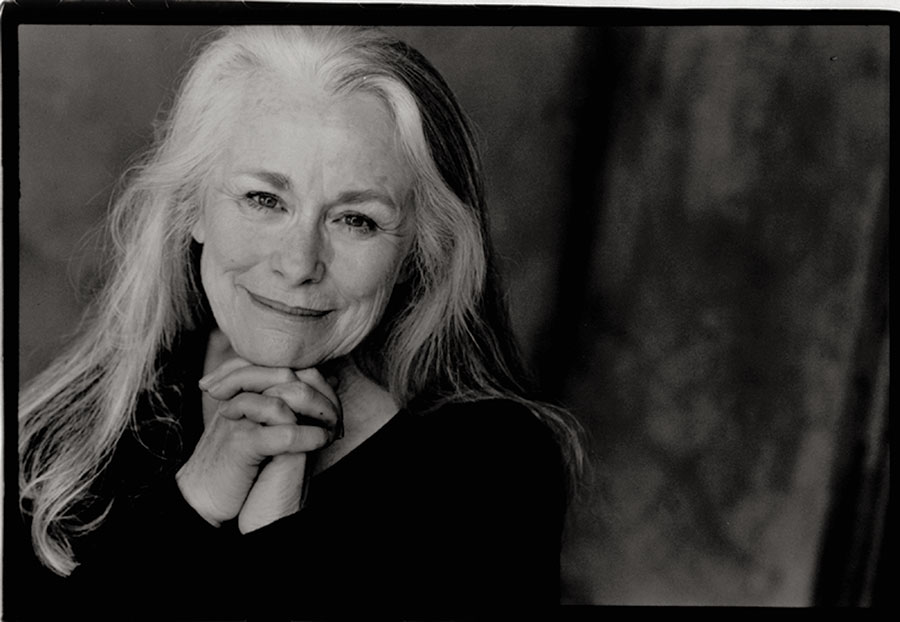

In Santa Monica, the Geers lived in a “fancy house,” employed a maid, and had “beautiful bikes,” remembers their daughter, Ellen Geer, now 75, who spoke to me in late April from her office. With a flow of long silver hair, a sparkle in her eyes, and animated gestures, Ellen sat in a rolling desk chair within a cabin-like structure in rustic Topanga Canyon, 25 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles, part of the campus where she now runs the outdoor repertory theatre Theatricum Botanicum, which her father, Will Geer, founded in 1973.

Those halcyon days of the ’50s would come to an abrupt end when Will Geer was blacklisted for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee against his colleagues. Will’s income ground to a halt, and his family split up. Yet what Ellen remembers most vividly about those harrowing years is how, despite all those travails, her father harbored no signs of spite. Years later the director Elia Kazan, who had infamously named names to that same committee, was casting the movie of William Inge’s Splendor in the Grass. When Ellen saw the casting notice, she asked her father if she could go to New York City to audition. Without a trace of bitterness, she recalls, “Pop said, ‘Go. Go.’”

Ironically it was Kazan who still had an issue. Ellen says that when her name was announced at the audition, Kazan was standing; as he saw her enter, “He turned bright red, he backed up and sat down. Then he asked, ‘How’s your mother? How’s your father?’” Ellen says she never even got to audition: “The man was so shattered and shamed by seeing me there.”

And she remembers that Morris Carnovsky, one of the founders of the Group Theatre in New York, who was named by Kazan to the committee as a Communist, was furious when he learned that Ellen’s father even allowed her to audition for Kazan. But Geer-fille counts herself grateful for her father’s example.

“I learned from Pop about not having bitterness—it was the greatest lesson in my life,” she says. “How do you take these things that happen in life, and how do you keep going and try to do better as a human being?”

After the Geers lost their home, Ellen says she attended “14-15 different schools” and was harassed at each. “Having things thrown at you, screamed at, kids chasing you down a street, calling you ‘Little Commie’—things like that. It’s like you’re not allowed to be! That’s why mother brought us up here,” to Topanga Canyon, a relatively secluded enclave in the Santa Monica Mountains. Even in the mid-’50s, before its hippie heyday, Topanga Canyon was a refuge, a bit like Prospero’s island.

The kids ran around barefoot, Ellen recalls; they lived on water drawn from a well. They raised chickens. “We lived the best we could,” she says. More important, nobody in the canyon cared about HUAC or about Hollywood celebrity. It became a kind of artists’ colony; no less a personage than Woody Guthrie had a shack there for a time.

“I was brought up to sit in the back of a truck and play the banjo and sing for a union,” Ellen remembers. “When you see people who want to move forward and they don’t have money, one response is to sing, to inspire. That’s what Pop tried to do.” Though the family had money troubles, Will eventually achieved a coveted sinecure with a role as the kindly grandpa on the TV series “The Waltons,” which ran 1971-81 (past his death in 1978).

The patriarch’s TV money helped bankroll the beginnings of a theatre company, which in effect turned a Topanga artists’ colony into a going nonprofit concern that now boasts a budget of $1 million and produces a summer festival season in a lush outdoor amphitheatre. And with his own children and grandchildren added to the company, Will Geer’s Theatricum Botanicum, as it’s officially known, has the makings of a family dynasty.

Named after John Parkinson’s 1640 botanical treatise, Theatrum Botanicum, the theatre has two striking features: The verdant campus is populated with a sample of every plant found in Shakespeare’s plays (Will studied horticulture at the University of Chicago). And though the productions, still performed in repertory, blend new works and classics, almost all are presented through the lens of politics.

“I don’t want to do Pajama Game and Oklahoma!” Ellen explains. “Other people do that just fine.”

But with some exceptions, such as Marc Blitzstein’s 1937 pro-union opera The Cradle Will Rock, staged by Theatricum in 2001, the politics comes more in the framing than in the texts themselves. Ellen says she believes that theatre and politics are best absorbed by “osmosis,” by demonstration, and by enjoying what somebody else does.

Ellen Geer didn’t have only her father as a model for what she’s doing now: She was in the founding companies of William Ball’s American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco and of Tyrone Guthrie’s in Minneapolis.

“I was so lucky,” she recalls. “I had Guthrie, John Houseman, Douglas Campbell, Ellis Rabb, and Rosemary Harris to learn from. I just watched what they did and absorbed it. You went out there and made huge mistakes.” You could learn from others’ mistakes too, she notes: “Bill Ball—he was as mad as a hatter, but he was inspired.”

As a director, Ellen says she believes in providing political contexts for larger discussions rather than mere pedantry. Theatricum’s production of Romeo and Juliet, for example, which she’s directing for the third time this summer (it runs June 4-Oct. 2), is set in East Jerusalem, where Jews are living alongside Palestinians.

“We’re doing it because it doesn’t take sides,” Ellen says of Shakespeare’s doomed romance. “It just shows what happens to love when there’s a culture of hate.”

Gerald C. Rivers, a company member for 20 years, recalls Ellen’s production of Measure for Measure, set in the 1960s, “against the backdrop of a country where the people were unhappy with the leadership, and the leaders set themselves up as moral vanguards.” Ellen put the character of Martin Luther King Jr. on a roof behind the audience. Without altering a word of the play, the framing device lent a starker political resonance to Shakespeare’s complicated fable.

And last year her staging of To Kill a Mockingbird had audiences lining the rafters.

“When the mob shows up to lynch Tom Robinson—in the book they are townspeople,” Rivers explains. Ellen put the mob “in KKK robes and had them come through the audience with axes and shotguns and billy clubs.” During a performance attended by schoolchildren, one school raised a complaint that there was no warning about the Klan members, and that their presence created discomfort.

Rivers remembers the reaction of fellow cast member Earnestine Phillips to the complaint: “They have no problem with the ‘n’ word used 22 times in an hour, but with a costume that’s not in the book, it’s too close for comfort?”

Phillips, an African-American performer who’s been with the company for 25 years and has played roles ranging from Queen Margaret to Caliban to Goneril to Bottom, joined before diversity was a hot-button topic. “I appreciate her for letting people of color come in,” Phillips says of Ellen, “and knowing that we can handle the classics, that our rhythms fit right in with everyone else’s.”

Alan Blumenfeld, who has acted in the company since 1984, points out the intersections of Ellen’s literary, political, educational, and spiritual missions. “I remember when we did Merchant of Venice, [Ellen was] looking at how it can be spiritual as well as educational and political. She sees the opportunity for education in the broadest sense, in terms of bringing these texts to young people as well as seeing the humanity of the plays.”

With a political legacy grounded in indignation over the inequities of Herbert Hoover-style economics, and fueled by the countercultural ferment of the late ’60s and early ’70s, Theatricum Botanicum seems suddenly hyper-relevant in the year of Bernie Sanders. It must have been quite a slog for the lefty theatre through the “Me Generation” of the ’70s and Reagan-Bush years. Certainly funding was tougher to come by in those days, Ellen admits. But Theatricum Botanicum has always had a robust youth education program, “and the NEA has always funded buildings and education,” she says.

And then along came Bernie. Ellen can barely conceal her excitement that the Vermont senator’s “political revolution” has ignited an entire generation of under-25-year-olds—the very audiences she strives to entice, and, perhaps not coincidentally, affiliated with the same values she emulates.

“Sometimes, as I’ve gotten older,” says Ellen’s daughter Willow Geer-Alsop, “I think my parents have gone even more to the left than me, with the things they say. ‘Really, guys, are you sure you looked that up, or is it something you just made up?’” She adds, “My mom used to wear bell-bottoms; I thought that was so uncool.”

Willow is Ellen’s daughter by her second husband, musician Peter Alsop, and has appeared frequently on the Theatricum stage. Willow prides herself on being contrarian, but also thinks of herself as the voice of reason.

“I didn’t have the ’60s,” Willow almost laments. “I was an ’80s kid, the generation of apathy, of ‘what’s on TV?’” Her parents gave her “a beautiful window onto what it’s like to have a call to civic duty, and I feel a lot of my friends just don’t have that. Maybe people need to get knocked down really hard to a place of desperation before they come around.”

Willow recalls bringing friends home for her birthday party when her mom and her aunt Melora Marshall were rehearsing a Woody Guthrie tribute. These friends, who came from tony Pacific Palisades addresses, walked in just as Marshall was “playing accordion, singing at the top of her lungs, [Guthrie’s “Union Maid”]: ‘Oh, you can’t scare me, I’m sticking to the union till the day I die!’ I didn’t even think that would be a weird thing to walk into as part of a birthday party.”

When it came time to prepare the current season, Willow wondered to her mom why she would dedicate a summer repertory to such serious plays, “all these downers”: not only Romeo and Juliet set in Jerusalem but also an adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (renamed Tom, June 18-Oct. 1) and a futuristic Titus Andronicus (July 30-Oct. 1), about unhinged politicians ignoring the people they’ve pledged to serve. (There’s also The Imaginary Invalid, July 9-Oct. 2, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, June 5-Sept. 23.)

“She says, ‘That’s what the world is going through, or is going to go through,’” comments Willow. “She’s always got the young people in mind. I worry about our ability to do that once she steps down. It’s not one of those gifts you can just pick up.”

It’s not for a lack of family feeling: As Willow recalls, “When I was a baby, she always strapped me on her back—that was the way we were a family. The closeness.”

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Willow plays Titania, and her own son Julius plays the fairy baby. That marks the fourth of Geer generations on the stage there: As Willow recalls, “Even my grandma, Herta Ware—when we did The Cradle Will Rock she was suffering from dementia, but Mom just put her on the stage, and she was right at home.”

If its links to the past are visible, Theatricum’s commitment to the future is no less strong.

“You can’t hoard what you know,” says Geer. “You have to share it.” Phillips remembers Ellen’s advice, “Stay around young people. They’ll keep you young.” The theatre’s School Days education program, which has been going strong since 1979, is now run by Elizabeth Tobias, who showed up as part of that program when she was in junior high and has been overseeing it since 2000.

Tobias notes that she has always focused on working with the classroom teachers on curriculum, not simply on busing kids in for a lark. “This is not a student matinee,” she insists. “This is an education program, and I take that very seriously.”

Ultimately the theatre’s future may come down to the core philosophies Ellen Geer learned from her father: Try to forgive. Strive to learn and to inspire. Care for others.

“You don’t teach by preaching,” Ellen says. “You teach by the way you live your life.”

Steven Leigh Morris is a playwright, journalist, and novelist. He currently serves as executive director of LA STAGE Alliance and teaches at California State University, San Bernardino and Dominguez Hills.