In 1998 our fledgling troupe, the Troubadour Theater Company, was 3 years old. We had performed at a few venues in L.A., Santa Monica, and Orange County, never really landing anywhere. Content to remain a touring company, we were still young.

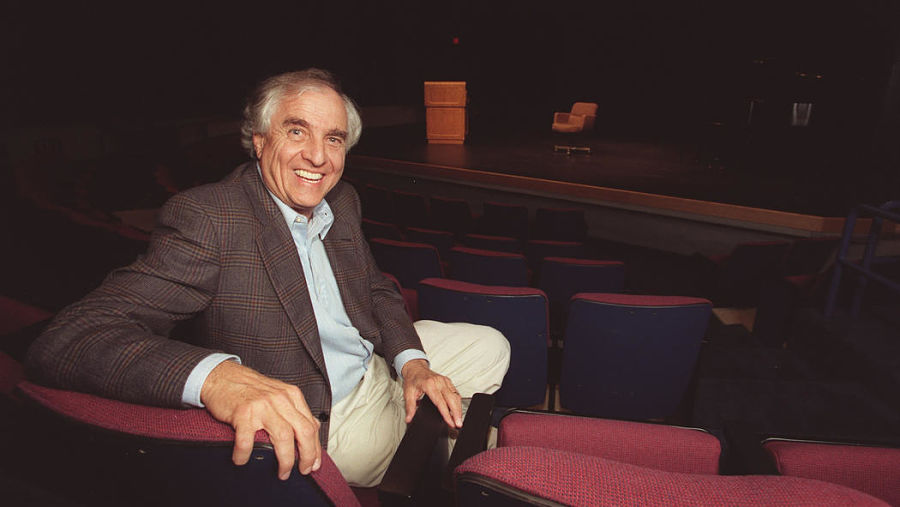

Then one day we got a call. One of our company’s actors had gone to high school with the son of a showbiz legend who happened to have recently opened a theatre in the valley. We’d been granted a 20-minute appointment to perform a selection of our current show for an audience of one: the theatre’s proprietor, Garry Marshall.

Now, everyone knows Garry made movies. Pretty Woman is beloved, Princess Diaries is charming, The Other Sister is sublime, Flamingo Kid is cool and hip, Valentine’s Day broke box-office records, and on and on (there were 18 feature films in all, with other greats including Young Doctors in Love, Nothing in Common, Georgia Rule, and Runaway Bride). And some of us probably remember that he created a few hit TV shows because we grew up on them: “Happy Days,” “Laverne & Shirley,” “Mork & Mindy,” “Angie,” and of course “The Odd Couple.”

He wrote for everyone from Lucille Ball and Dick Van Dyke, from Taylor Swift to Ludacris (with no beefs!). He’s a member of the Television Hall of Fame, has a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, and created iconic characters for actors that have helped launch their careers into the stratosphere (a short list: Ron Howard, Henry Winkler, Penny Marshall, Anne Hathaway, Julia Roberts).

And we had a 20-minute audience with this guy. Gulp!

Who knew this guy loved working in the theatre? I didn’t. I had no idea he was a playwright as well, having penned shows including Everybody Say Cheese, Wrong Turn at Lungfish (which starred George C. Scott), and a play that reached Broadway, The Roast, directed by Carl Reiner and starring Rob Reiner, Peter Boyle, and Bill Macy. It lasted a grand total of 9 previews and 3 performances before closing in 1980. Still counts.

Garry later worked with composer and hit songwriter Paul Williams to bring “Happy Days” to the stage. After its creation at the Falcon and subsequent workshop productions at the Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey and the Goodspeed in Connecticut, “Happy Days the Musical” began its national tour in Milwaukee (where the TV show was set) in the winter of 2009, and has since made its way around the world.

Most recently, before he died last week, Garry had been collaborating with director/choreographer Jerry Mitchell, screenwriter J.F. Lawton, and songwriters Bryan Adams and Jim Vallance to bring a musical version of his classic film Pretty Woman to Broadway in 2017.

In his memoir, My Happy Days in Hollywood, Garry talks about seminal theatrical performances he’d witnessed, including seeing Julie Andrews on Broadway in My Fair Lady. He remarks about the power of theatre to transform and captivate the way no other medium can.

His passion and love for the theatre was such that he decided to build one in Burbank, across the street from the Bob’s Big Boy, which on Friday nights during the weekly classic car show could have stood in as the location for Arnold’s Drive-In from “Happy Days.” Together with his daughter Kathleen, they created a beautifully adorned, perfectly intimate 135-seat gem of a theatre in the shadow of nearby Warner Bros. studio. The Falcon Theatre was named after Garry’s teenage athletic club in the Bronx, and augmented with a state-of-the-art projection system for screening Garry’s most recent day-job project.

Showcasing new works as well as classics, the Falcon quickly became not only a cozy neighborhood theatre where you were almost sure to see Garry in the parking lot helping stack cars, but a wonderful creative incubator that attracted Hollywood heavy hitters interested in keeping their skills sharp and enhancing their craft under the creative supervision of an entertainment supernova.

Garry threw himself into all aspects of the process. Casting, script doctor, set design, you name it. Sometimes he’d take the stage and deliver curtain speeches on opening nights, reminding people that even if they didn’t care for the play, they’d gotten free parking.

So…like I said, we had 20 minutes to make an impression on this man. Our conundrum at the time was: Which 20 minutes from our current production of Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost (retitled Clowns’ Labours Lost) should we show him?

We knew he played sports, because the display cases in the lobby of the Falcon were filled with framed photos and championship trophies from his co-ed softball team. So we made the decision to perform only our most athletic bits. Having just graduated clown college with Ringling Bros., I had infused the with stilt walking, trampoline, slide table, and endless slapstick (again, we were young).

Without ever bothering to rehearse our theoretical cobbling-together of “greatest hits,” we showed up and were greeted by a liaison of the theatre who told us to set up quickly. We learned that Mr. Marshall would be coming from a meeting, was heavily scheduled, and that our 20 minutes were sure to be cut short.

Moments after we had dressed and set up, the house right door opened and in walked Garry Marshall. Alone. He made his way up the stairs, and we all noticed a paper sign taped to a seat in the seventh row, house right, on the aisle. It read “Reserved.” Funny, I remember thinking—did someone on his staff do that, even though they knew Garry would be the only one in the theatre? He took the paper off, smiling, and sat down. We mentally thanked paper-sign-maker, whoever it was, for the audience warmup, and pondered a workplace where people had fun with the boss.

Then he checked his watch. (Gulp.) The liaison signaled to begin, and without another word our canned Shakespearean music started and we were on the clock.

Not rehearsing the transitions between the physical gags ended up being a blessing and a curse: a blessing because those were the only laughs we got out of Garry. Having to improvise and fly by the seat of our pants in front of someone who has already heard every joke ever told, and probably wrote or punched up most of them, was what made an impression.

And it was a curse because, never having performed all of our most taxing and vigorous bits back to back to back, the gambit proved unwise from a health and well-being standpoint. After our 18-minute running time—emphasis on running time—we held hands as a cast and took our curtain call for a standing ovation of one. Then I promptly ran to the restroom and heaved my guts out from sheer exhaustion and nerves, while others combatted onset asthma in the green room.

While I was toweling off (and holding a waste basket) in the dressing room, wondering why the liaison hadn’t come backstage yet to thank us for at least ending two minutes early, Garry Marshall himself walked in.

His praise was effusive, even though we knew we were spotty. He instantly put us at ease with his affability, charm, and graciousness. He was completely authentic as he thanked each of us in turn, introducing himself as “Garry Marshall from Show Business.”

He told us how much he appreciated the athleticism; in his words, “You were peppy and jumping and hopping all over the place!” Then he interviewed the cast again to ask who could play softball. He made us laugh, even though that was supposed to be our job.

His parting words that day about our potential future under his auspices: “Let’s give it a shot!”

That “shot” has lasted for 18 years over 30 original shows and one Crystal Cruise; almost two decades of blessed mentorship and collaboration with one of the all-time greats. When we needed it, he was honest. When we couldn’t be, he was funny. And always in between there was love and support, and handwritten notes on yellow legal pads that would inevitably be posted on the callboard in a gilded frame like the Magna Carta. We too had fun with the boss.

His stewardship, warmth, and generosity of spirit have nurtured countless artists through his theatre, and the Falcon will continue his legacy of respect for artists, his belief in the transformative power of theatre, and his lifelong mantra, “Make ’em laugh.”

If you’re ever in Burbank and catch a show at the Falcon Theatre, seventh row, house right, on the aisle—sorry, it’s reserved. But as always the parking is free.

Matt Walker is a director with Troubadour Theater Company.