“Technology” can be a scary word if you’re a parent. The dangers of too much screen time are a constant worry, not to mention the threat of sexting and cyberbullying. Still, policy experts agree that technology has great educational potential, and according to the Family Online Safety Institute, most parents believe technology has a positive impact on their children’s lives.

Theatre companies seem to agree. New York City’s New Victory Theater has been embracing technology in children’s theatre for years, by presenting multimedia work and incorporating texting into pre- and post-show family events. Nine of the 12 shows the theatre will present in its 2016-17 season include projections, and companies that stop at New Victory on tour come in with increasingly sophisticated design elements.

“Companies can now get their costs down far enough and do more innovative things because they can employ technology so efficiently,” says David Jensen, director of production at New Victory. He notes that the cost of using projections has come down in recent years, as has the cost of show controller consoles that allow shows of any size to achieve big effects. “It’s great for the artists to be able to use the combination of lights and imagery to help tell their story.”

Two shows in the New Victory’s upcoming season demonstrate the new tech landscape particularly well, using multimedia to serve the story and connect performers and audience members. The first is 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which will open Sept. 30. The production was created by Canada-based Kidoons/WYRD Productions in association with the 20K Collective. Collaborators Craig Francis and Rick Miller combine a steampunk aesthetic with projections and live-feed video to create a world that pays homage to Jules Verne’s 1870 novel while giving the story a contemporary feel.

“We decided early on that there would be a lot of movement in the play because the book implies movement,” says Miller, who cowrote the piece with Francis and also directs. “We wanted to take the kind of creativity that Verne was exemplifying in his book, with regards to technology, and apply it to today. So we go from sophisticated multi-projector video mapping to manipulating action figures in front of a camera, and we really enjoy that playfulness.”

Francis adds that the show’s use of technology echoes how forward-thinking the book was at the time of its publication. “Captain Nemo is foreseeing the submarine and oxygen tanks,” explains Francis. “He’s foreseeing uses of electricity far beyond lighting and power. So it was exciting to see how we could update that.”

Francis and Miller continue the multimedia experience in their work with a network of videos on the Kidoons website. Before and after the show, audience members can view videos of recurring cartoon characters interacting with characters from the company’s theatre productions and exploring the shows’ themes. “Our mandate is always to develop outreach, to educate and entertain kids, and this is where they’re starting—on a screen,” says Francis.

“You don’t put all of your effort into one show that tours and dies, and your study guide is forever a pdf,” adds Miller. “It’s something that’s continually expanding and growing.”

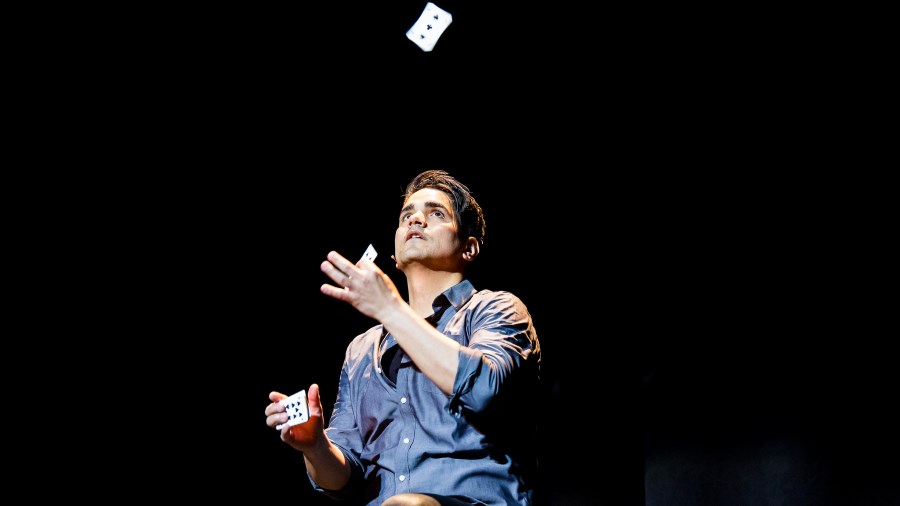

Also in New Victory’s upcoming season, Jason Bishop: Straight Up Magic uses some of the same effects as 20,000 Leagues to put a new spin on a traditional magic act. Bishop’s show, which opens Nov. 18, includes illusions that feature LED lighting, GoPro cameras, smartphones, and plenty of audience participation. He also transmits live video to plasma screens on the sides of the stage, which allow audience members to view small tricks up close.

“Magicians throughout history have always been early adopters,” Bishop says, citing chemistry and film as two of the fields that influence magicians. “We accept technology quickly and integrate it into our shows, and that catches people’s interest. You’re using something the audience is familiar with, but in an unfamiliar way, and people really respond to that.”

New Victory’s Jensen observes that the ability to run lights, sound, and projections from one master console is also crucial to streamlining the technology for both shows. “In the old paradigm, you would have three people running those cues, and a fourth person to call the show,” he explains. “Now one master voice sends out a trigger that can make cues happen simultaneously. This allows Jason to do some really cool reveals that would have taken a lot more rehearsal and work to get the timing perfect. He’s able to do it in a much more controlled fashion.”

While technology is a major component of these productions, the artists involved stress that its role is to enhance the theatre experience, not to replace it. “Technology is flat and shallow if it’s just played for what it is,” says Bishop. “But if it’s a vehicle for a joke, or for amazing people in a way they’ve never been amazed before, or as a vehicle for sharing communally, that’s interesting.”

“It’s not just tech for tech’s sake because it’s cool,” adds Miller. “As anyone who’s a parent knows, kids with screens are disconnected. We’re not just trying to play with technology in an interesting way, but to speak about technology.”

Jensen points out that young audiences tend to look at shows holistically anyway, as opposed to favoring moments that use technology over others. “Kids come in with fewer preconceived notions about what the piece is going to be, so they don’t single out projections the way adults might,” he says. “Kids just respond to the show itself.”

Miller maintains that even the most bare-bones productions engage with technology in some way. “People who object to the use of technology in theatre forget that it’s possible that theatre came out of technology,” he says. “When people were gathered around the fire and someone cast their shadow against the wall and pretended they were a giant or a monster or an animal, that’s technology. I tend to think we’re just following in that same tradition.”