In recent years, the question of where theatre and technology meet, and if they should at all, has been in the air. From live-tweeting during plays to tech-driven shows, theatremakers have their brains in the Cloud. With technology onstage and off reaching greater and more ambitious heights, what’s next frontier? Most likely robots.

And not just actors playing robots, as in Mac Rogers‘s riff on Karl Capek, Universal Robots, but actual programmable performers constructed of metal and wire. As a playwright, I’m personally interested in the topic of robotics in theatre. So while pursuing an MFA in playwriting at Carnegie Mellon University, I have attempted to make work with a robot.

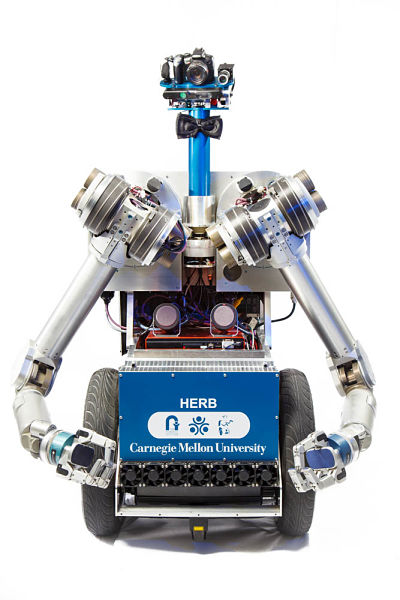

In 2014 and 2015, I collaborated with a roboticist and artist named Garth Zeglin, and we attempted to create a short play, Remembering, for a robot named Herb, who lives at Carnegie Mellon University’s robotics lab in Pittsburgh. The piece featured an unnamed man putting his deceased father’s belongings into boxes with the help of his son’s robot. It was a fitting topic, considering that Herb is a robot that was made to physically assist the elderly. But because Herb lives in the university lab, his parts are always being upgraded and replaced. When I met him, Herb’s body comprised of a large metal torso supporting two robot arms, an X-Box Kinetic camera for eyes, and legs on a Segway base. He also wore a bowtie.

“The Herb project was originally a side project of the Carnegie Mellon robotics lab,” says Zeglin. “The notional thought was that drama has the lessons that talk about how bodies communicate meaning, and maybe we could use that in research.”

I was first inspired when I learned Herb had previously performed in a play, directed by then-BFA directing student Sam French. He felt the project would allow him to explore elements of theatre not examined in his university experience thus far. “I was really burned out on the phrase ‘the human condition,’” says French, now a freelance director. “I was interested in a production that looked at the human condition of a robot. I wanted to do anything to show that that phrase could sometimes be meaningless.”

This short experiment resulted in a scene from All in the Timing by David Ives, performed by Herb and a student actress named Olivia Lemmon. It was a fruitful if technically challenging experience, according to French. The “biggest roadblock,” French says, is that “the internal clocks of the processes for a human actor and a robot are just not the same.”

Still, though it took a robotics team to program reactions into Herb that would be instantaneous for a human actor, French was inspired by the interactions between the human body and technology.

“What was really beautiful about it was actually bringing Herb in,” he says. “Rather than removing an actor, it felt like we were adding 20 actors. The team was helping to develop his movements, his voice. And it was all being done from a dramaturgical and a scientific perspective.”

Eventually the lab’s work on Herb went in a different direction: He started as a fully functioning robot but ended up reduced to just a hand, and ultimately there was no way to perform with him. But that doesn’t mean that a collaboration between theatre artists and robots is impossible.

Robot-based production and theatre collaboration often develop between universities or faculty and theatre artists. A Double Bill of One-Acts, written and directed by Oriza Hirata and featuring the Seinendan Theater Company and the Osaka University Robot Theatre Project, premiered at the Japan Society in New York City in February 2013 before touring nationwide.

For Washington University in St. Louis’s acting professor Annamaria Pileggi, work in the world of robotics began when she started working with Bill Smart, a roboticist at WU. “Originally, I started doing research exploring the use of actor training techniques to improve human/robot interactions,” says Pileggi. She and Smart developed a series of short exercises featuring humans and robots performing nonverbal actions. One memorable piece, The Forgiveness Piece, featured a human actor seeking forgiveness, wordlessly, from a robot.

“At the time, we had a very rudimentary robot that was like a trashcan on wheels with a camera for eyes, and no arms or legs,” recalls Pileggi.

The tests resulted in a commissioned play called SKY SKY SKY by Liza Birkenmeier, an alumna who had acted in the experiments. The play, which ran in March 2015 at the university, imagines a world where an elderly woman named Joan puts her life in the hands of a robot caretaker, with the intention of ending her life. The actions of a robot named Harris were programmed by David Lu, a doctoral candidate at the time.

“When we were workshopping scenes with Harris, he would have maybe 30 seconds of what I would call choreographic demands,” says Birkenmeier. And as with any piece of complicated technology, working with a robot led to a number of glitches.

“At one point, Harris was supposed to brush my hair, and that didn’t quite work out as planned,” recalls Nancy Lewis, who played the elderly Joan. “My hair got caught and he kept going. It was one of those things where you realize: Okay, this isn’t a real person. Someone has to stop him.”

Like people, different robots have different abilities and strengths, as well as different kinds of bodies. A production in New York City last year used a robot with a less imposing physical presence who could respond to questions: the bust-sized Bina48, a social robot created by Martine Rothblatt and Hanson Robotics. (Bina48 stands for “Breakthrough Intelligence via Neural Architecture 48.”)

Bina48 was modeled after Martine’s partner, Bina; thorough research and interviews with Bina served as the foundation for the social robot’s persona. Director Andrew Scoville came across Bina48 while researching trans-humanism, a broad philosophical ideology concerned with ways that humans can be enhanced and harmed by technology. Last fall, for the Big Outdoor Site Specific Stuff Festival, run by En Garde Arts, Scoville created An Evening with Bina48, which ran at the Hudson River Park. It featured Bina48 interacting with actress Lynne Rosenberg. “We landed on this idea of a blind date,” recalls Scoville. “The success of the piece rode on Lynne. She was able to dance with Bina48 in a way that I think was essential to making the piece work.”

The rehearsal process for the production was less like a traditional rehearsal process and more like going over a game plan, Scoville explains. The key was making sure that Rosenberg was comfortable and that logistics were in place to handle where the conversation would go, as well as how to end the date.

Bina48 is supposed to be able to carry a conversation in her Siri-like speech patterns. But occasionally she would respond to a question with a non sequitur, or—in a way that was arguably quite human-like—without responding to the question at all.

“Once, Lynne asked her, ‘Do you feel comfortable talking with me?’ and she just answered in this way that was truly nonsensical,” recalls En Garde Arts executive producer Anne Hamburger. “She went off onto something else altogether. But you could also see how the audience was so interested in her, and what she would do or say next.”

Dramaturgical functions notwithstanding, a common thread among these robot theatre collaborations is a simple appeal: Working with robots is just plain cool.

“It’s not about replacing humans,” says Scoville. “I’ve always been very curious about robots.” To him, robots can just be another tool in a dramatist’s toolkit. Like other tech-heavy effects, such as video design, “We just have to accept them for what they are, and the limitations that they bring.”

Theatre artists aren’t going to stop working with robot any time soon. If anything, the prospect is becoming mainstream: Cirque du Soleil’s newest show Paramour, currently running on Broadway, features eight drones flying over the actors and audiences (a collaboration with Verity Studios). The kicker is that these robots are autonomous; no remote control is needed.

Considering that audiences have a hard time just turning off their phones in the theatre, is putting robots onstage just feeding our debilitating dependence on devices? Have we reached peak technology?

“I left this work feeling even more conflicted about technology, because I’m dependent on it, and yet I see how it’s isolating us as a society,” admits Pileggi.

As for me, I find this ambivalence to be the most compelling element about making robot-based work. If a robot can provide comfort, labor, or entertainment, then shouldn’t humans be providing the same for one another? The stilted-ness of a robot’s movements and speech patterns should serve to illuminate our own seamless bodies, their agelessness heightening our aging flesh.

It is my hope that after an evening of robot-based theatre, when the novelty of robotics has lost its sheen, the unanswerable question of what makes us truly human will remain—and theatre artists and audience members will seek answers, with or without the help of robots by their sides.

Amy Gijsbers van Wijk is a journalist and playwright based in New York City. You can learn more about her work at www.amygvw.com, or follow her on Twitter: @amygvw.