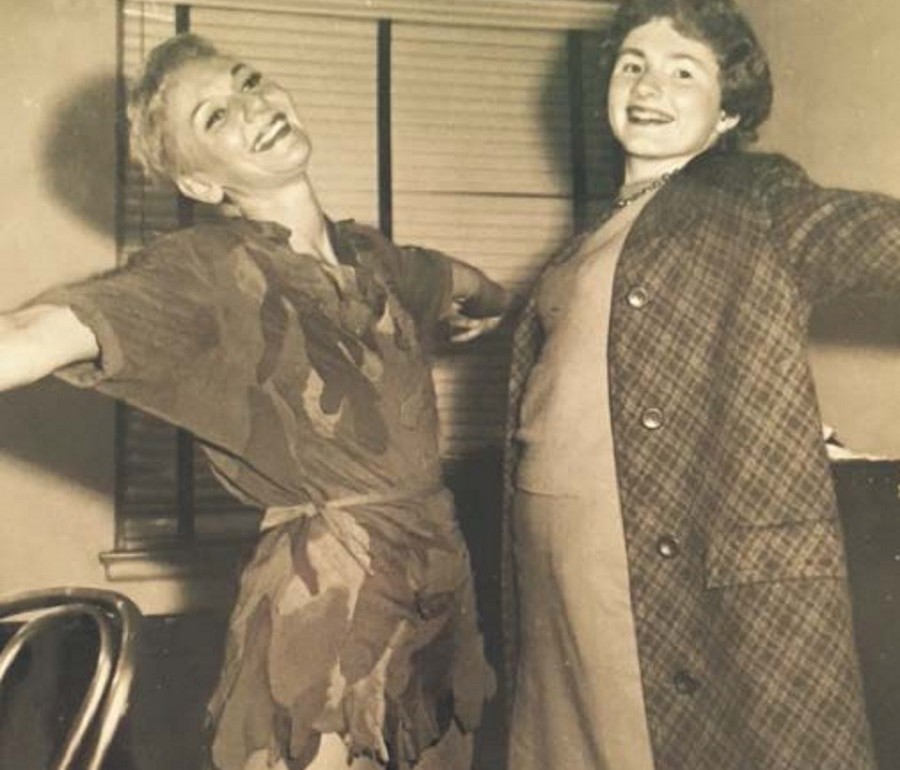

I grew up seeing pictures of my mother all over the house flying, in green tights. She played Peter Pan as a girl in Davenport, Iowa. I was also mesmerized by a photo taken by the local paper of my mother as a teenager standing next to Mary Martin (pictured here). My early love of the theatre was formed in the crucible of my mother’s flight, as it existed in memory. A year after writing For Peter Pan on her 70th Birthday for my mother, I sat down with her in Evanston, Ill., where she lives, to ask her a little bit about her long life in Chicago theatre.

Can you talk about flying as Peter Pan when you were growing up?

The first year we did it, the flying wasn’t very good. You passed across the stage a couple feet above the floor, and it was very painful. The harness cut into your legs, and they padded us with Kotex to try and make it feel better. But the second year the flying was really good. I’m an extremely nervous flyer in airplanes, but I liked flying if it appeared to be of my own volition.

Can you talk about your acting career in Chicago and where you started out?

The Easter of my senior year in college, I took the bus to Chicago and got a job as Bob Sickinger’s secretary at Hull House Theatre. Bob Sickinger was quite a character. He had absolutely no interest in me as an actor, only an interest in me as someone to stuff envelopes, so it wasn’t very satisfying. But shortly thereafter I got involved with the Chicago City Players, doing several shows there directed by June Pyskacek. Much later, TimeLine Theatre took over that same space, and I’ve been in several shows with them as well (Gaslight, Dolly West’s Kitchen, and This Happy Breed, which got a Jeff award for best ensemble). It took my breath away when I realized at my first Timeline rehearsal that the last show I’d done in that space on Wellington Avenue had been 25 to 30 years earlier.

You’ve been involved with a number of companies in Chicago that you work with over and over again—TimeLine, the Piven Theatre Workshop, and most recently Redtwist Theatre. Can you talk about that ethos of Chicago theatre a little—the storefront theatre and the nature of ensemble in Chicago?

The theatre community in Chicago feels larger than one company; there are a lot of Chicago actors who belong to more than one company. People know each other and go back and forth even between Equity and non-Equity companies—this is true of actors, directors, and designers. TimeLine started as a non-Equity company; so did the Piven Theatre Workshop. It’s incredible. When I came to Chicago in 1964, there was Hull House Theatre, a non-Equity, off-Loop theatre; there was a summer theatre called Court Theatre at the University of Chicago, which was outdoors; there were dinner theatres; road companies of Broadway shows; and that was it. And now it’s incredible the number of indigenous companies there are here—Chicago is a wonderful place for young people in theatre. It’s fine for old people too.

You said once when you did an Equity show at Court Theatre (Hay Fever) that you were so astonished that a dresser washed your stockings out for you every night. Can you talk about working at larger theatres like Court Theatre or Writers Theatre after working with smaller companies?

Certainly there are more people working the backstage end of things in larger theatres. You don’t have a dresser in storefront theatre. But if you have really quick changes, someone from the cast is pressed into service. In a certain sense, what I’m noticing now is the professional ethos that even the storefront theatres have—they all have dramaturgs with packets for us; we now have understudies.

So that’s different from when you started out doing the plays of María Irene Fornés, Megan Terry, Jean-Claude Von Itallie, and Sam Shepherd in Chicago?

Now the people who work in storefronts have also been to theatre school; back in the day most hadn’t. When I was first at the Chicago City Players, I remember the stage manager coming backstage and saying, “Kathy, curtain.” But at Timeline, we’d get, “15 minutes,” and everyone answered, “Thanks, 15,” as they’d learned to do in theatre school. That’s a small thing, but I think it speaks to the idea that people in storefront theatres now think of themselves as professionals, which is different from the ’60s. Then, we thought of ourselves as professional in terms of commitment to our work, but we weren’t paid; it was the actors doing dinner theatre who were paid. We didn’t have systematic training. We thought of ourselves as artists.

How weird was it for you to see your life history portrayed by Kathy Chalfant in For Peter Pan on her 70th Birthday?

What’s weird is that it wasn’t weird. I knew the script—it wasn’t a surprise—although there were some surprises in the production. I did the role in one reading and it felt very natural. But it didn’t feel unnatural seeing someone else do it.

Did you see Tracy Letts’s father do August: Osage County?

Yes, I did.

I loved his portrayal so much. Do you think there’s something about the familial nature of theatre in Chicago that impacts something like that choice of Tracy’s? I know you did a reading of his play at Steppenwolf the day he found out about his Pulitzer Prize.

That’s right, Superior Donuts. There are a number of theatrical families regularly working in Chicago and sometimes even working together. The Pivens—Joyce, Byrne, Shira and Jeremy. Mike Nussbaum and his daughter Susan. Jessie Mueller and her sister and her father Roger and his wife. Jessica Thebus and her mother, Mary Ann Thebus. Paula Scrofano and John Reeger, who were given a lifetime achievement Jeff Award together last year. They have managed, without doing any commercials, to make a living as theatre artists in Chicago—to own a house and to send their children to college—which is pretty remarkable.

You won a Jeff Award too.

For supporting actress, yes, for Dolly West’s Kitchen at Timeline, directed by Kimberly Senior.

How did it feel, after working for so many years, to get a Jeff?

It wasn’t so much about working so many years, it was about having watched awards ceremonies for so many years—the Oscars, the Tony Awards. It was more about a sense of playing a role in that drama—the drama of the awards show. Years ago, I had heard Zoe Caldwell accept her Tony, saying, “Being nominated with all of these people is wonderful, they are the crème de la crème—but to win is marvelous.” And since then, I had thought that the concept of being nominated is really the thing, to be recognized as one of the good performances in a year when there are so many of them, and that’s how I felt when it happened to me.

I was reading an essay about women and ambition recently, talking about the idea that recognition is really important for everyone, and how historically, women have been unable to demand recognition or show any desire for it. But it’s really a basic human impulse and part of why we make work and part of what sustains us. Was getting recognition in that way important to you?

That’s so interesting, because I guess I feel the extent to which I am ambitious is the extent to which I feel guilty about it.

Well, you were raised Catholic.

Yes, and in my journals from high school, which I still have, I would say, “Oh God, help me to get 100 on the test tomorrow and also be a nice person.” Everyone says the work is the thing and really it is.

Back when I wrote poems, I was really interested in the idea of writing occasional poetry, for other people, as gifts, which is really old-fashioned in the poetry world.

Funnily enough, your grandmother was famous in Davenport, Iowa, because she always wrote poetry for occasions.

That’s right. A couple of years ago I got the idea, after reading Lewis Hyde’s The Gift, that plays could be gifts just as well. Most family dramas are about exposing terrible secrets, not about giving a gift to someone you love. I was also inspired by Quiara Hudes’s beautiful trilogy, in which she asked questions of her family as part of her process. Part of the fun for me was being able to ask questions of my family that I normally wouldn’t ask, like: Do you pray? Do you believe in an afterlife, in God? What do you think is wrong with this country? So for me, it was an excuse to have conversations with living people rather than with dead people. I wrote Eurydice to have one more conversation with my dad, who was not alive. And Peter Pan was pointedly different, a way to get to know my living family better.

I’ve talked about that many times—the fact that you interviewed us all and asked us the same questions as the way to make a conversation happen in the play. In recent years, our conversations have been fraught because of political differences, and everyone being sensitive about them in different ways. And it was nice to see us talking in the play in an intimate way. It’s a wonderful gift, an amazing and beautiful gift. I love it, and just hope I get to do the part some time.

I’m sure you will! We are plotting to do the play together somewhere in Chicago in the future, directed by Jessica Thebus. We’re in conversations with Shattered Globe, which, like so many Chicago theaters we’ve talked about, also has a wonderful ensemble…