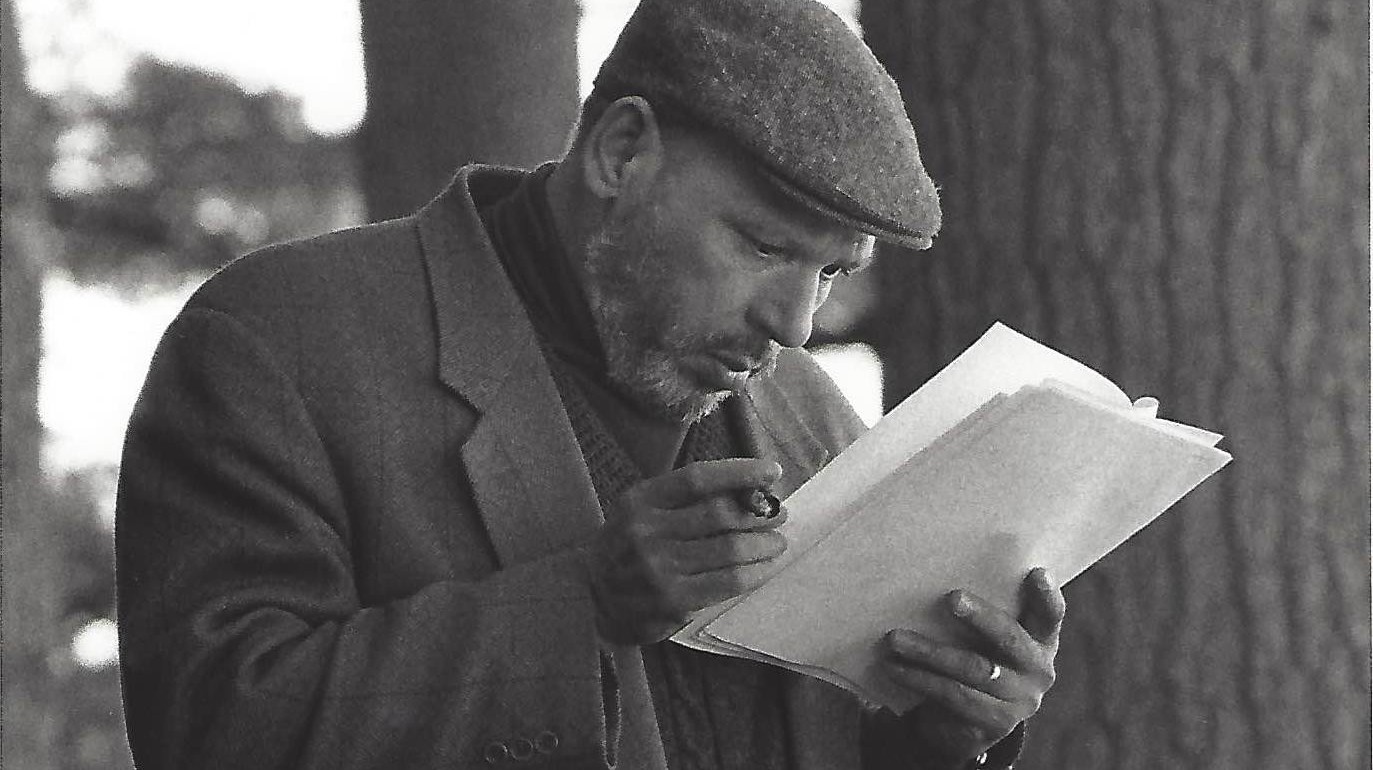

Twenty years ago, on June 26, 1996, before attendees of the 11th biennial Theatre Communications Group (TCG) National Conference at Princeton University, the late, great playwright August Wilson delivered his now famous keynote address, “The Ground on Which I Stand.” His remarks immediately went viral—or whatever the equivalent was in that Internet pre-dawn. At a time before the phenomenon known as #blacktwitter, let alone Twitter more generally, Wilson’s speech sent reverberations across the world of American theatre as well as that of black politics. In the aftermath of the TCG conference, debates raged across the pages of national newspapers, journals, and periodicals, including American Theatre, which offered special issues with invited responses to the address. The speech spawned a new organization, the African Grove Institute for the Arts (AGIA), in 1998, and encouraged the subsequent Black Theatrical Summit, titled “On Golden Pond,” at Dartmouth College in March of that same year. Published and widely disseminated, the speech has become a critical black theatre manifesto, studied alongside W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Four Principles of Negro Theater” (1926) and Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones’s “The Revolutionary Theatre” (1966).

Looking back 20 years later on Wilson’s now-hallowed “Ground” from the perspectives on race and theatre that we have attained in 2016 enables us to appreciate its prescience, as well as to recognize the yet unfulfilled vision expressed in Wilson’s fiery jeremiad. There remain too many spaces in African-American life and arts where the ground is still “hard and rocky,” as Wilson’s character Rose points out in Fences. Wilson’s “Ground” foregrounds these racial inequities. At the same time, with urgency and purpose, Wilson’s TCG talk conjoins the lessons he learned from Western theatrical forebears such as Aeschylus and Shakespeare with those of African-American revolutionaries such as Nat Turner and Marcus Garvey. Thus, even as “Ground” points to black difference and the uniqueness of black experience, it also identifies a space for cross-racial communion in the shared heritage of theatrical practice. Given our current national climate of dissent—present in everything from 2016 presidential debates to the mood on college campuses—such community and communion across difference have seemed most difficult to achieve. Reexamining Wilson’s “Ground,” in this final year of the tenure of America’s first black president, Barack Obama, reminds us, paradoxically, how far we have come but also just how far we still need to travel theatrically and racially in a country that is clearly not “post-racial.”

As cases in point, the heated demands and urgent cries of unrest recently emerging on college campuses, ranging from the University of Missouri to Yale, have direct parallels to Wilson’s 1996 TCG address. With a certain bold irreverence, black students have called to account the institutions to which they belong. To date there have been protests and demonstrations at more than 60 universities in the United States and abroad. Some detractors have accused the student protesters of being too coddled and overly sensitive. Others have pointed to the contradictions inherent in students at an elite institution protesting that very elitism (how could, for instance, a black Rhodes scholar at Oxford call for the removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes, the creator of that very scholarship?).

Wilson’s “Ground” received a similar backlash and critique. Notably, in his address Wilson—the most performed American playwright in the decade of the 1990s—assailed the very regional theatre structures that facilitated his climb to that pinnacle. Some deemed him ungrateful. Prominent critics such as Robert Brustein, in “Subsidized Separatism” (AT, October 1996), Stanley Crouch in “Who’s Zooming Who” (1997), and Henry Louis Gates Jr. in “The Chitlin’ Circuit” (1997), immediately attacked Wilson for what they deemed as his divisive and naïve black activism. Others inside and outside of the theatre praised Wilson for his courage and insight in speaking “truth to power.”

Significantly, in his TCG address originally delivered before a predominantly white audience, including several regional theatre managers who had produced his plays, Wilson suggested that it was his particular vantage point that facilitated his penetrating insight. The ground on which he stood, as an insider who because of race and circumstance was also an outsider, enabled him to speak out against what he termed “cultural imperialism” and systemic racial discrimination. It is precisely this same position of paradox—being at once within and outside the institution, feeling part of the school yet also alienated because of the university’s racist past and microaggressions in the present—that has empowered black students to speak out against problematic traditions and the perpetuation of racist systems. Accordingly, both Wilson in “Ground” and protesters on campus argue that it is not enough for institutions opening the doors to include black voices; the institutions themselves need to change.

The Black Lives Matter movement that originated in 2013 after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of teenaged Trayvon Martin also resonates with the sentiments Wilson expresses in “Ground.” The movement has responded to the urgent need to address collectively and publicly the issues around state-sanctioned violence in the killing of black youths. It has also sought to broaden this discussion to consider black disempowerment more generally by connecting the disenfranchisement of blacks with other issues of oppression, including sexual discrimination. The movement has become a political force that, according to activist Brittany Packnett, a member of President Obama’s task force on police reform has succeeded in “connecting the dots for people and weaving a broader story about systemic injustice so the masses could understand life as a black person in America.” The Black Lives Matter movement has tried to bring new light to social injustices and proclaim the need for fundamental human rights and dignity for all black people.

Correspondingly, Wilson’s “Ground” exposes the separate and unequal conditions of black and white lives. He chastises both the American governmental and theatrical systems that continually denigrate and diminish black worth. With the evolution of Internet and the online presence of #blacklivesmatter, social media has become a key site both to exercise and to foster black self-definition as well as a space to organize and develop social resistance. Lacking this new technology, Wilson called for direct face-to-face action. He wanted black playwrights and artists to form a united front and give “expression to the spirit that has been shaped and fashioned by our history.” Wilson imagined black theatre developing into a powerful cultural force, not unlike what the Black Lives Matter movement has become, that celebrates a shared legacy of struggle and survival.

Instructively, in “Ground” Wilson makes the claim that African Americans specifically, and Americans more generally, cannot avoid the impact of history. For him, history was always present. Thus, the contemporary circumstances of black Americans, with the repeated incidences of police violence on black bodies, with the increasing erosion of hard-won voting rights, are not new but are rather reverberations of historic injustices. The historical iteration of so many wrongs against black people testifies to the need to remember this long past and its reach into our present. Moreover, if we heed the lessons of Wilson’s “Ground,” we need not only to reflect on our heritage but act on it.

A Wilsonian recognition of history makes us realize that rather than just confronting each individual outbreak of racism, we need a more systemic approach. Wilson’s call is not for a passive remembrance of the past but for a historic recall that forces change in the present.

To our current age, which some may argue is removed from the racist indignities and racial exigencies of early periods of black struggle, and in which some black artists may no longer feel compelled to believe that all black art is or needs to be political, Wilson’s “Ground” continues to offer a sharp rejoinder. Situating himself purposefully as a “race man” in the tradition of Du Bois’s belief in art as always political, Wilson links African-American historic struggles for liberation with what he sees as the stunted development of African-American theatre. For Wilson, his own aesthetic practice emerged most directly from the heritage of his ancestors’ bloody resistance to oppression. “I stand myself and my art squarely on the self-defining ground of the slave quarters,” he wrote, “and find the ground to be hallowed and made fertile by the blood and bones of the men and women who can be described as warriors on the cultural battlefield that affirmed their self-worth.” Wilson identifies what he perceives as the functional connection of black arts to the cause of progressive struggle, and calls on his fellow black playwrights not only to recognize their collective destiny but to realize the activist potential of black theatre. As he puts it, “Artists, playwrights, actors—we can be the spearhead of a movement to reignite and reunite our people’s positive energy for a political and social change that is reflective of our spiritual truths.”

One could certainly argue that this charge has largely gone unheeded—that the current mechanisms of black artistic production in this time of highly diffuse and highly digitized media have not resulted in a unified vision of art for social change but rather in more individualized expressions of black realities. To be sure, significant new black playwrights, including Tarell Alvin McCraney, Lynn Nottage, and Danai Gurira, have appeared on the national stage. Yet there has not been the kind of unified cry through black theatre that Wilson desired. The AGIA plan to organize a comprehensive national black theatre has never materialized. Even as McCraney and Nottage have found celebrated performances at regional theatres across the country, their route to these productions has been similar to that taken by Wilson himself with his 20th-century cycle of plays: They have not been able to rely on the network of black theatres that Wilson hoped would develop but instead have had their success at large white-run institutions.

Of course, the most significant controversy triggered by Wilson’s “Ground,” and one that demands current reconsideration, is his condemnation of so-called colorblind casting. As he put it: “Colorblind casting is an aberrant idea that has never had any validity other than as a tool of the cultural imperialists who view their American culture, rooted in the icons of European culture, as beyond reproach in its perfection.” Some critics felt that Wilson was damning the efforts of regional theatres to diversify their casting and to employ people of color. Yet Wilson implicitly distinguishes colorblind casting—efforts to cast shows as if race does not matter—from nontraditional casting, which uses race, gender, and sexuality purposefully in nonconventional ways to comment on the play and its messages.

Moreover, Wilson’s denunciation of colorblind casting in “Ground” foregrounds the sober reality that in 1996 we did not—and still do not in 2016—live in a colorblind society. Accordingly, such casting efforts by theatres, while they may aim to construct portraits of inclusion, also, knowingly or unknowingly, attempt to render blackness and its particularities invisible. Wilson writes, “Many whites (like the proponents of colorblind casting) say, ‘Oh, I don’t see color.’ We want you to see us. We are black and beautiful.” His desire to depict and celebrate black difference motivated his indictment of colorblindness.

What, then, does Wilson’s “Ground” have to say to the current Broadway musical sensation Hamilton, and its casting of black and brown actors as great white men? Provocatively, actors of color play nearly all the major characters in Hamilton, including slave-holding Founding Fathers George Washington and Thomas Jefferson—who, as we now know, fathered children by black women—and bring new insights into these figures in the process. Through his selection of actors of color and his use of contemporary hip-hop, playwright/composer/lead actor Lin-Manuel Miranda has productively reframed the debate around colorblind casting. He engages in nontraditional casting which is decidedly color-conscious, as it compels audiences to understand the history of Alexander Hamilton as one that does not deny but rather acknowledges—indeed, embraces—race. One of Wilson’s assertions in “Ground” is that colorblind casting, with its disregard for race, functions as an “assault on our [black] presence and our difficult but honorable history in America.” Hamilton makes race visible and central to the American story, and in doing so recognizes that “honorable” black history.

Miranda retells the history of Hamilton as an immigrant narrative that resonates with the journeys past and present of many peoples of color from Latin America and the Caribbean to the United States. At the same time, he makes Hamilton much more of an abolitionist than he was in actuality by connecting the knowledge Hamilton gained from his childhood in the Caribbean to a position of continued anti-slavery activism. Wilson in “Ground” and throughout his dramaturgy strongly reminds us of the distinctness of the black passage to America, in that black people did not have the agency of traveling here as immigrants but rather endured lives as captives on slave ships. This experience, he argued, now profoundly informs our present. Thus, Wilson would differentiate the impact of slavery on the contemporary cultural consciousness of African Americans from the effect of slavery that Miranda attributes to the psyche of Alexander Hamilton. Still, like Wilson, Miranda underscores the presence of the past as he reframes the narrative of Hamilton and constructs a fuller vision of American history.

It is important to recognize that Wilson’s attack on colorblind casting was not a rejection of theatrical diversity and inclusion. Rather, he believed that the development of separate spaces for the advancement of black theatre would be conducive to the enterprise of American theatre as a whole: “To pursue our cultural expression does not separate us. We are not separatists…We are Americans trying to fulfill our talents,” he said. Wilson calls for greater black control of the politics of performance—the critical offstage resources that enable the financing and production of a show. Even with the success of Hamilton and the emergence of new black plays and playwrights, this last objective has remained largely unfulfilled. The space and places for new black work remain limited. The mechanisms of production, the control over venues, budgets, and artistic selections are for the most part not in black hands. Sadly, in cities across the country, black theatrical institutions such as the Lorraine Hansberry Theatre in San Francisco and the Penumbra in St. Paul, Minn., have struggled. The precarious situation that August Wilson decried for black theatre in “Ground” stubbornly continues to persist.

“We need theatres,” Wilson insisted. “We need theatres to develop our playwrights.” A bit ironically, Wilson now has a theatre that bears his name: On October 17, 2005, following his burial on October 8, 2005, the Virginia Theatre at 245 West 52nd Street in New York City became the August Wilson Theatre, making Wilson the first African American to have a Broadway theatre named in his honor. But, as it’s a commercial Broadway house, the August Wilson Theatre has thus far only hosted one show: the long-running, and very white, Jersey Boys.

Perhaps now more than ever, 20 years after Wilson’s clarion call—in a moment when on the one hand many speculate whether “race” exists at all, and on the other hand the increasingly influential Black Lives Matter movement has taken on a life of its own—perhaps now more than ever is a time in need of the establishment and rejuvenation of black cultural institutions. Vibrant, vital places to incubate, to develop and produce new plays; educational places that foster theatrical appreciation and facilitate audience development; critical spaces that enable and encourage the integration of scholarly examination and artistic experimentation are needed. This is the ground yet untrod, and we are called to claim it.

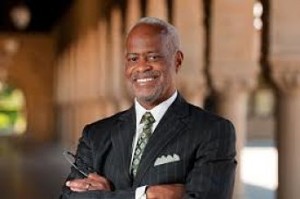

Harry J. Elam Jr. is the author The Past as Present in the Drama of August Wilson. Elam serves as the Freeman-Thornton Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education, the Olive H. Palmer Professor in the Humanities, and a Bass University Fellow in Undergraduate Education at Stanford University.

Harry J. Elam Jr. is the author The Past as Present in the Drama of August Wilson. Elam serves as the Freeman-Thornton Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education, the Olive H. Palmer Professor in the Humanities, and a Bass University Fellow in Undergraduate Education at Stanford University.