The playwright August Wilson moved to Seattle in 1990, as his widow, Constanza Romero, has explained, in a sort of compromise (she wanted the West Coast but he wouldn’t do California). You’ll hear a slightly different reasoning from Charles Johnson, the National Book Award-winning author of Middle Passage, MacArthur Fellow, and established cartoonist, essayist, screenwriter, novelist, and educator, with whom Wilson formed a strong friendship after he and Romero relocated to the Emerald City.

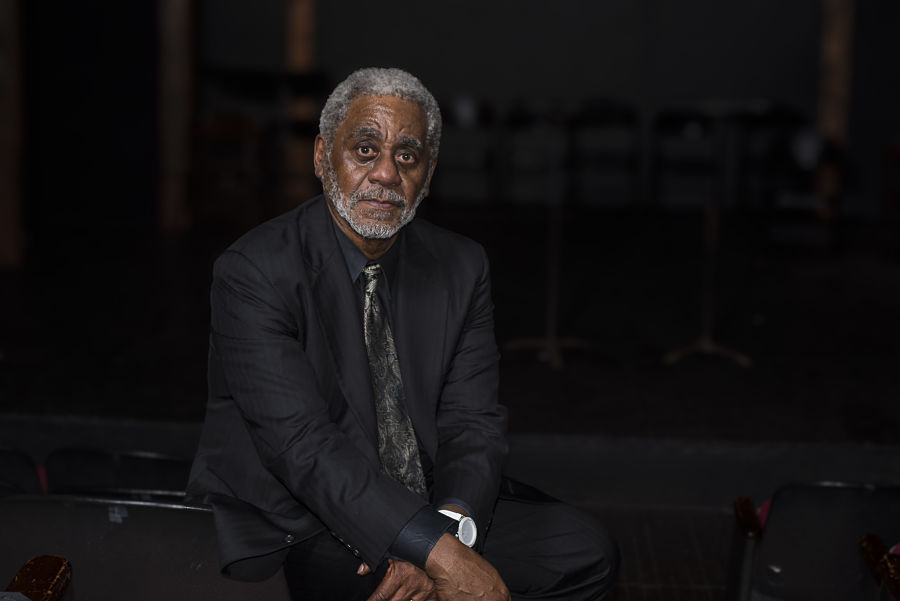

Now in retirement, Johnson sat down in May and talked with me in the faculty lounge at Padelford Hall on the University of Washington campus about his long friendship with Wilson, who died in 2005.

NATHANIEL G. NESMITH: You and August were good friends—you’ve said that “the 15-year friendship with August Wilson during his time in Seattle was an enriching experience for which I am thankful.” How did you meet and establish a friendship with August Wilson?

CHARLES JOHNSON: Well, I think I was invited to one of August’s plays at the Seattle Repertory Theatre, and I met him in the lobby just as my wife and I were going in to see the play. It might have been Fences. And I simply said to him, “Welcome to Seattle.” He told me later that I was the only person who had told him that when he came here to live. And it turned out, we ran into each other at the Broadway Bar and Grill on Capitol Hill. I was with somebody else who was following me around, Jonathan Little, who wrote the first critical book on my work. We just happened to stop at this place and August Wilson was there, sitting at a table writing. We made an appointment to get together there and have dinner.

Our dinners would start at 7 o’clock and we would go until 2 in the morning—until they closed the place down. And sometimes we would keep talking on the sidewalk at 2 in the morning and then go up the street and around the corner to the International House of Pancakes. And this is one of the locations I used in my story about August and me called “Night Hawks.” I don’t know if you have seen that or not, but Night Hawks is about our 15 years of eight-hour conversations.

You have lived in other places and Wilson also lived in other places. What is it about Seattle that made both of you settle here?

It’s a friendly city. August told me that he was thinking about going to Portland, Ore., but someone told him that there was no income state tax in Washington and he said, “That is where I am going to go then.” I came out this way because I got hired here at the University of Washington. They gave me early tenure in three years and they gave me an early full professorship in three years. I was done with the academic hoops you have to jump through after six years. So, it is a very easy place for me to stay. In the 1970s, it was like a small San Francisco—the composition of the people. It is a laid-back place. I think August felt the same way about it.

What is your best memory of August Wilson?

My best memory of August? I have so many it is hard to say which one is best. Some are memorable. I interviewed him onstage at the Seattle Repertory after a performance of King Hedley II, and that was a very nice evening. I asked him a few questions and then the audience did a Q & A with him. That was a good night. We had a lot of good nights. He participated in something I started here called Bedtime Stories, which is a yearly event where local writers read original stories. It is in support of Humanities Washington and their program for literacy and the humanities. Three times at least August wrote stories and appeared there. I have done it every year for 17 years. So, there is more than simply one best memory.

Do you remember the last conversation you had with Wilson?

Very well. It was brief. We didn’t meet until two in the morning, we met until midnight. That was as long as he could go because he had just found out that he was dying. He sent me a letter saying he wanted to have one more of our dinner conversations at the Broadway. We met there at seven and by midnight that was it. That was our last one. It was very painful for me. I was just incredulous that he only had three months to live.

What is it you regret that you did not do with Wilson?

Well, it is hard to say what I regret. He and I did have dinner one evening with the late novelist Oscar Hijuelos. We sat around and dreamed up a play we were all going to write together. And I remember after that dinner—the next day after that dinner August faxed me his four or five pages, contributing to this play. Oscar and I never got our acts together to pick up on it or run with it or do anything. So that is a play that did not happen, but one we were talking about doing, and August was rather enthusiastic about doing it.

As you know, there are always aspects of an artist that the public does not get to know. What insights could you share with us about Wilson that might surprise the public?

This is a tough one, because I may be saying something that is not an insight after all, but certainly is something that made a big impression on me. I think August’s public image is that of a militant black writer. I remember at one meeting of playwrights he made the statement that he was a “race man”—that he was with the field Negroes and not the house Negroes—a sort of militant kind of image. But this was a man for whom the creative impulse, I think, was first and foremost. It transcended politics. If you are a real artist, you need the creative process, expressing yourself, the way people need air, the way people need food. It is necessary for your existence. It is not like you choose it, even as a career—it chooses you. I had the blessing of knowing on this campus Jacob Lawrence, who was working, painting until the last day of his life; he was in the art department. August was the same kind of an artist. He would always be creating. It would not always be something necessarily political. I don’t know if that is an insight, but it was what impressed me about him. I could see a man for whom the creative spirit was his life’s blood.

You and Wilson were both respected and established artists. What similarities did the two of you share as artists and what differences separated you two as artists?

I think both of us were very enthusiastic about any creative project. Like I said, he fell into this proposal that he, Oscar Hijuelos, and I do a play together—he fell into that with great enthusiasm, as something that would be fun to do. Art is a form of play on a certain level, regardless of how serious it might be. I shared that, about getting excited about creative work.

What difference separated you two?

I think our background. August didn’t like people being critical of the 1960s and the Black Arts Movement. He said that was his growing up period—a period when he came into himself. I remember the Black Arts Movement, but I was not a part of it. It was always peripheral to my thinking. Although I knew people who were involved in it in the Midwest, it was not central to my way of thinking.

Wilson started out as a poet and established his career as a playwright. In your case, you’re a cartoonist, essayist, screenwriter, non-fictionist, and a novelist. Can I get away with referring to you as a non-fictionist? Anyway, the point is, you have covered a wide path as a writer. What is it that you gained from Wilson that aided you in your progress as a writer?

What I gained was a spirited 15 years of dialogue with another black male writer who had traversed the American political, cultural, and racial landscape since the late 1940s and early 1950s, same as I had. We had passed through the same world. I think there was only three years difference in our age; he was maybe three years older than me. We knew the same cultural world. It was always a joy to talk with another artist with whom I shared this life experience of being a black man in the second half of the 20th century.

You also said that race was a subject that Wilson thought about all the time, 24/7. Would you expand on that premise?

Since the last time we met, we would sit down and talk about racial things that happened in his experience and nationally and so forth. His wife, Constanza Romero, once told me that he enjoyed having someone who would listen to him talk. He would talk for a long time and at great length about racial issues. Now, August had a hard time, he told me, understanding how people could say race was not real—that it was an illusion. That is my position. My position is that race is a lived illusion. It is a social construct. I remember him saying to me that you could look at people and you could see people are from different races. That is what he said. But sometimes you cannot look at people and know that they are from different races—all those black people who pass for white, you can’t tell, or people who are biracial, you can’t say they are one race and not another race. Like Obama, he is biracial. But August had a hard time; he thought there was something essential to race. And I don’t believe that there is.

Did you ever talk to him about his white father?

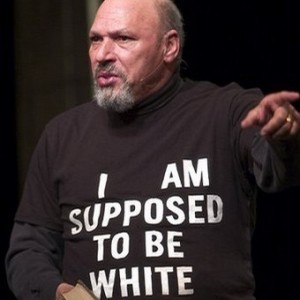

Not much. I think he may have referenced it once, saying he was not around much. But I got the impression that the absent father was very important in August’s life. Now, he always talked about his mother in glowing terms—beautiful tributes to her, Daisy. But the father, no. I was talking to a friend of mine; he is black and we were talking about August, and he said something that was very intriguing: The play about his father is the one he really wanted to write but didn’t. I can understand that, because it would be painful. It would be a painful thing to have to do. I remember August had a one-man show that he was doing toward the end of his life. I didn’t see the show itself. I saw a photograph with him wearing a T-shirt and the T-shirt said, “I’m supposed to be white.” I could not believe he put that T-shirt on and went out there onstage. He did. People would mistake him for being white. He told me, for example, about taxi drivers who thought he was white, and they would all of a sudden erupt with some racist statement about black people, not knowing he was black. There was a white man at one of his plays during the Q &A who asked him, “How did you learn so much about black people?” August said, “I learned it from my mother.” The man then gasped; he mistook August for being a white person. So I think there was something there that August did not really express in play form. If that was a play, it would be very hard to write because it would have been so intensely personal.

Wilson definitely subscribed to a black aesthetic, whereas I would say that you do not. Did you and Wilson ever talk about the idea of black aesthetics?

Not really. I know he was a big admirer of Amiri Baraka, very big admirer. When he would see him he would start to recite one of his poems—they both were poets and then playwrights. I would imagine August would say many of the same things Baraka would say and Toni Morrison, who is also a product of that period. When she says, “White people write for white people and why can’t black people write for black people”—that is a Black Arts Movement line from the late 1960s, probably specifically from Baraka or Larry Neal, one of the other founders of the Black Arts Movement. The Black Arts Movement did not last that long, it was over by the mid-1970s. Baraka himself had moved away from it to what he called scientific socialism—he gave it up. But August held on to certain ideas that were current at that time. I don’t think they were necessarily bad ideas all the time.

Wilson was concerned with history, which is the foundation of his cycle of 10 plays. History is also a major factor in your work, from Dreamers to The Middle Passage. Did you and Wilson ever have conversations about the significance of history in either of your works?

We talked about it. August once asked me some questions about the Middle Passage and how the sailors might have treated black women on the ships. I didn’t really have an answer for him. I knew what he was looking for. I did not have an answer that would have satisfied him by saying, “Yes, the sailors did that.” We were much immersed, both of us, in the history of black people in this country and in the world. There is no question about that.

What do you think Wilson gained from you artistically?

We were talking one evening—I am a Buddhist, I have a background in Eastern philosophy—I told him about a verse I like very much from the Bhagavad-Gita, The Song of God. He told his wife about it and so she asked me to give her the verse for his birthday. I believe I sent it to Constanza, the original Devanagari characters, plus transliteration and the translation. This is the verse that August liked, from Book 2, Verse 47 in the Bhagavad-Gita.

Your right is to action alone

Never to its fruits at any time.

Never should the fruits of action be

Your motive.

Never let there be attachment

To inaction in you.

I live by that verse. I memorized that verse. I can go on about it. August told an interviewer that I shared this with him and he believed it. That is how he saw his own work: You don’t work for the fruits of action, for the rewards, you work for the virtue of the action alone. You are not working for fame, fortune, glory, and all of that. You are working from a very different sense, and I believe that is true of August.

Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray were very good friends and their politics were similar. You and Wilson were good friends—you said you were like brothers—but your politics were not similar. How did you two cross the bridge of having different politics?

Like I said, the fact that August was a true artist to me transcended political difference. He might take this position on an issue to the left; I might take this position on an issue to the right. But the fact of the matter is he is a true artist. And that is what I responded to. It is okay to have difference of opinions in different ways, because when he sits down to do his art, it will come out of a place that is very pure and is not didactic. It is going to transcend momentarily political stuff.

When you consider all of Wilson’s plays, which one engaged you most and why?

I have to put it this way: I think Jitney is a real crowd pleaser. I have framed posters for two of his plays in our TV entertainment room; I have posters for Jitney and King Hedley II.

You are not only an artist but also an educator who has had many students. If Wilson were one of your students–knowing his work as you do—what advice would you offer him?

In the Chronicle of Higher Education around 2002 or 2003, I published an essay on how I taught a “boot camp” for creative writing. It is also in a new book coming out in December called The Way of the Writer. August read the essay and he said when he read it that was the one time he regretted he did not have a chance to go to college. He dropped out of high school when he was a freshman, as you know. I think what he would have appreciated was the rigor with which I tried to get my students to become writers who could take on any assignment, and who were prolific. My students turned in three craft exercises a week from John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, three stories, which they revised in a 10-week period of time. They had to critique each other’s work with sophistication and they had to keep a journal. I gave them a lot of work. I think he missed that kind of instruction.

Now, since The Middle Passage has been adapted into a play—it will go up in December at Pegasus Theatre in Chicago, with the title Rutherford’s Travels—do you think knowing Wilson as you did provided insight into the process of having a play produced?

The play adaptation is very new to me at this point. Last month I saw for the first time the play in a staged reading with some music in the background. I saw what they had done with it. I did not talk to them prior to the adaptation. I made one note to the director about a character’s speech in the middle of the book, and that was all I said in terms of comments. I have not been hands-on involved with the adaptation in the way August was. Sometimes towards the end August was directing his own plays. I am still learning about what they are doing with the play.

Wilson’s “four Bs” are well known. Less well known are his four rules, which are: 1, There are no rules; 2, The first rule is wrong, so pay attention; 3, You can’t write for an audience; the writer’s first job is to survive (italics mine), and 4, You can make no mistakes, but anything you write can be made better. What credence do you place on those four rules?

I think they work. I think they make sense. I think the first rule is funny. There are no rules. Then he turns around and says the first rule is wrong. There are no hard and fast rules. But there is a general temperament that artists have, and the last one certainly captures that temperament that you can’t do anything wrong, but anything you do will be improved by revision and going back over it again. And I like the other point that he makes: You can’t write for an audience, and an artist’s first job is to survive, because it is not easy to survive as an artist anywhere, but certainly not here in America. We have a constant struggle here between art and commerce. Artists can tell you, whether they are actors, dancers, writers, or poets, how difficult it is to be an artist in America.

This is what Wilson said about you: “Charles Johnson is a friend of mine in Seattle. Charles threw away 2,500 pages! It blows me away to this day…That’s like 10 books just to get to that one. And that’s work, but he wasn’t afraid to do the work. And that’s how you learn it, in the trenches. Do it, do it, and do it.” Do you think Wilson was also in the trenches, and how so?

When he wrote his plays, I don’t know—I don’t know his ratio of throw-away-to-keep pages. Sometimes my ratio could be 20-to-1 throwaway pages to one final page. Revision is 90 percent of the creative process. It is also the most fun part of the creative process. I generate lots of pages for a novel. Now, I think August understood intimately and from the inside how that being in the trenches, as he called it, is characteristic of the artistic process, whether it is with plays or with novels.

Finally, this is what Wilson said: “The big difference in writing a novel is that the narrator can take an audience to places you can’t on a stage. What I can do in a novel is to take you down this dusty road and have you taste the dust. Suddenly it gets dark and two million crows come flying across going south. They black out the sun. I can’t do that onstage. But in a novel I can make you see those crows and have that mean something. I’ve got about 60 pages of a novel. Notes. A page here, an idea there. It really wants to be born. On occasion I have dinner with Charles Johnson, and every time I tell him I want to write a novel but that I don’t know how to do it. I can’t see the form of a novel—this vast ocean where I really don’t know how to get from here to there. I tell him that for me writing a novel is like being on an ocean without a compass. And he says, ‘Well, go find a compass!’ So I guess that’s what I have to do. As soon as I find a compass I’ll take a shot at it.” Wilson never got to write the novel. Do you think he had the right stuff to be a good novelist?

Yes, I do. For example, the descriptive passages that you would have in a novel, I think he would fall to those with the skill of a poet, because he was a poet. I think what he probably would have had to begin to feel from the inside is the form of the novel and the way you could possibly do it. Now, novels are not hard to write. You can teach somebody the basic tools for writing a novel in 10 weeks. I used to do that. The basic tools can be taught in 10 weeks because there aren’t many: characters, plots, description, narration, voice—six or seven different things. You put them together in different arrangements. You might have alternating first-person viewpoints. You might have the third-person viewpoint. Once you learn what those tools are and how you can use them imaginatively, a novel is not hard to write. I wrote six in two years before I published my first one.

But you are exceptional.

I don’t know how exceptional—I just grew up in an environment where hard work was not something to be afraid of.