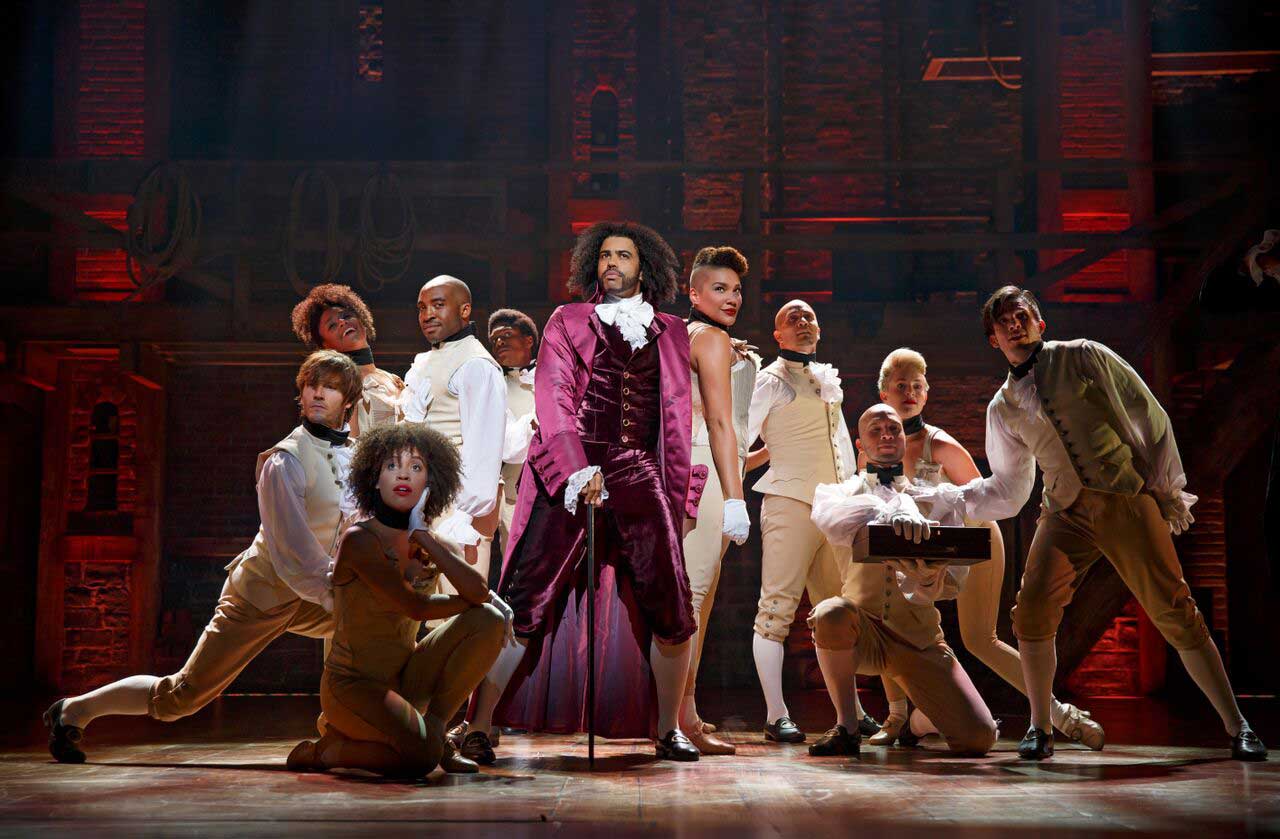

NEW YORK CITY: The Great White Way has never been as ill-fitting an appellation for Broadway as it was this past season. Shows all along the district have presented a wonderfully diverse range of voices and experiences, from The Color Purple to Allegiance to On Your Feet!. And this is all happening under the giant shadow of Hamilton, with its rapping founding fathers and a cast that is almost entirely African-American, Latino, and Asian.

Amid a panoply of directors, playwrights, and performers of color, it is easy to overlook that this is an unusually diverse season for designers as well. Emilio Sosa, who is black and from the Dominican Republic, designed the costumes for On Your Feet! Riccardo Hernandez, who is Latino, did the costumes and sets for the Gin Game revival starring James Earl Jones and Cicely Tyson. Toni-Leslie James, a black costume designer, channeled the 18th century for Amazing Grace, the short-lived musical about slavery and the eponymous Christian hymn. And this season there were two costume designers of Asian descent at the helm of high-profile shows: Anita Yavich for the revival of Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love and Suttirat Anne Larlarb for the Sara Bareilles-composed musical Waitress.

You may not see this backstage diversity reflected on Sunday’s Tony Awards broadcast, though, since only two designers of color employed this season were nominated for Tonys: Clint Ramos for Danai Gurira’s Eclipsed and Paul Tazewell for Hamilton, both for costume design. (Ramos also designed the set for Eclipsed.)

Tazewell, a black costume designer for whom this represents a sixth Tony nomination, is excited not only about his nomination, but also about what shows like his say about the current state of Broadway.

“The possibility has opened up for a new way of telling a story, presenting an idea, presenting a musical,” he says. “It’s no longer as interesting to see a Broadway musical served up in the usual way.”

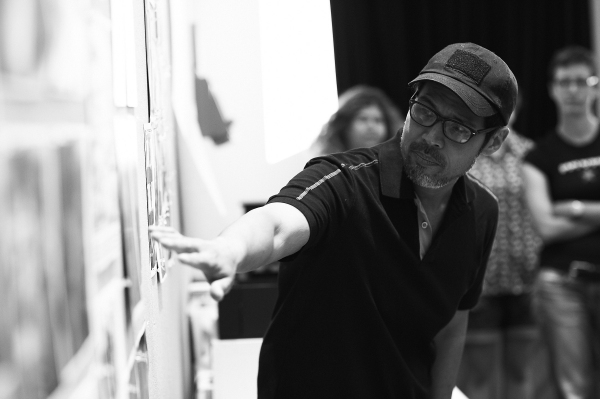

This is Ramos’s first Tony nomination, and even as he celebrates the diversity among this season’s design pool, he bemoans that designers aren’t more visible to the theatregoing public.

“There were quite a number of designers of color this year, but you don’t see us,” says the designer, who is of Filipino descent. “It’s hard for us to get any attention. A lot of people ask, ‘Where are the designers of color?’ And I always say, ‘We’re out there! We’re just as busy as other designers!’ But we work behind the scenes, so we can’t get as much attention as the people onstage.”

Although it is par for the course that designers of all backgrounds stay out of the spotlight—and many of them prefer it that way—Ramos thinks this invisibility exacerbates the diversity problem in design. Though there has been no demographic study about designers on Broadway specifically, a recent study from the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, which surveyed 1,000 cultural nonprofits, found that out of 346 theatre designers polled, 81 percent were Caucasian (the percentage was the same for the 1,676 technical/production staffers polled).

“There is a dearth of young artists of color going into design for the theatre,” says Ramos. “And part of that is because they don’t see themselves in it. I never saw people who looked like me. I was never exposed to them. I had to seek them out.” It creates a vicious cycle, he explains. “How can we address the problem when we can’t attract young artists of color into the design field?”

The answer may be to start at the institutional level. Cecilia Friederichs, the national business agent of United Scenic Artists, a union for designers and scenic artists, says that the stage design field is having a conversation now not only about racial equity but gender disparity as well. Apart from the category of costume design, women are woefully underrepresented in all categories of USA’s membership. And according to a study released last year by the League of Professional Theatre Women, men Off-Broadway outnumber women in all backstage disciplines save for costuming and stage management. The union has formed a diversity committee this year to address both gender and racial equity in theatrical design, and plan out action steps to promote both.

Still, on the production end, small changes can be made to highlight more of the creative team beyond just the directors and writers. Ramos believes that designers’ names should be included in the publicity materials for shows.

“It’s important that people see my last name there,” he says. “Because I think young artists will see a last name like that and think, ‘Oh, there could be a place for me there.’” He cites a trend about 20 or 30 years back that saw some female lighting designers using only their first initials and last names to increase their chances of getting hired in a male-dominated field. “I understand. They wanted to even the playing field. But I think it also didn’t serve a lot of women designers because it masked the reality.”

Tazewell believes that a big part of the burden for fostering diversity falls to the people at the top. “It will take forward-thinking producers and directors asking designers [of color] who are just great designers period,” he says. “Inviting them to design Shakespeare, inviting them to design Ibsen, inviting them to design a musical that’s all showgirls and sparkles.”

Tazewell’s résumé also includes a number of African-American-centered productions, which he is proud to have been involved in. But to him one of the great frustrations for designers of color is being told that they “should be working on a production that is specific to a diverse story.” It’s ironic, considering that audiences never see the designers. “There is no reason for Broadway or commercial producers to distinguish between designers of color and white designers,” Ramos says. “Unlike with casting, we have the benefit of the fact that it doesn’t really matter what we look like. If the design is good, it doesn’t matter.”

In this sense, Ramos suggests that the invisibility factor goes both ways: It may be harder to see designers of color than actors, but it’s easier to hire them based on skill—that is, if you can find them.

Over at United Scenic Artists, the diversity committee is working to address the disparity by urging established designers of all backgrounds to hire and mentor assistants from a more diverse pool. Explains Friederichs, “We’re interested in getting involved in encouraging people to choose assistants in a way that fosters a growth of diversity.”

There are also hopeful signs on the national level. Crowded Fire Theater in San Francisco, for example, provides grants and professional development to Bay Area designers and technicians under the auspices of its Ignite Fund, described in its official wording as having “an eye toward supporting the plurality of race, culture, class, gender, and age in our local design and technical community.” And Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. has an internship and fellowship program for designers, technicians, and administrators, named after Allen Lee Hughes, a black lighting designer who has worked at the company since 1969.

Ramos also cites the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival as two companies that, in his experience, have made it part of their core mission to attract diverse theatre artists. The Guthrie offers internships and a job fair for artists on and offstage. OSF offers a fellowship and residency program, called FAIR, for theatre practitioners, including designers.

In spite of the headway being made on Broadway and beyond, though, it remains to be seen whether this season was an inspiration or aberration. There have certainly been other years when Broadway has offered daring fare and showcased underrepresented groups: Take 1996, when the proto-hipster musical Rent, August Wilson’s Seven Guitars, and George C. Wolfe’s black history musical Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk (with costumes by Tazewell) were all up for Tonys, and many thought it heralded a new age. But the next year it was back to the safety (and predominant whiteness) of A Doll’s House, Chicago, and Titanic. (Notably, there was a Broadway revival of The Gin Game that year as well, starring white actors Charles Durning and Julie Harris.)

Both Ramos and Tazewell maintain a cautious optimism toward the current moment. “I think if you asked people of color, most of us have a guarded sort of stance,” says Ramos. “We think of it as a blip, something that may not happen again.”

“I am hopeful that this is the direction we’re moving in,” says Tazewell, “but history has proven that there’s a pendulum. The pendulum I think will start to widen, start to open up more possibilities, but it is bound to shift back, because that is the nature of the beast.”

Ramos pointedly cautions that the work is not over. After all, this has been a notably diverse season for designers only in relative terms.

“We’ve certainly made strides in terms of diversity on Broadway,” he says. “but for designers and people who work backstage, it’s still not as diverse as we want it to be.” For him, the key is to take the present momentum and keep on moving forward. “If we in the American theatre are really invested in diversity and the breadth of human experience, then it is imperative that we populate our industry with more designers of color who, just by the nature of who they are, offer a different worldview, with a different body of experience.”

Pamela Newton is a freelance writer and college writing teacher living in New York City.