In 1976, the first issue of PAJ—then titled with the full name Performing Arts Journal—was published, the brainchild of Bonnie Marranca and Gautam Dasgupta. Since then, for the past 40 years, three times a year, the journal has been at the forefront of innovative, serious criticism of theatre, performance art, and the disciplines that interact with it. A typical issue features essays, reviews, and reports from around the world, not to mention play texts and, increasingly, portfolios of visual art related to theatre and performance. Among the authors PAJ has published in its distinguished run, both in its journal and in its rich catalogue of books, have been Eric Bentley, Maria Irene Fornes, Susan Sontag, Heiner Müller, Stanley Kauffmann—a roll call of many of the most important artists and critics of theatre and drama of the past half century. It continues to publish some of the most important essays and criticism by theatre artists and writers, young and old, to this day.

I first joined PAJ as an editorial assistant when I was fresh out of college in 1983. I proofread, typeset, and filled book orders—and, by osmosis, I absorbed some of the exciting energy that animated the downtown art scene of the period. Bonnie and Gautam became good friends, as did a few other members of the office help, among them Eszter Balint—a former member of the Squat Theatre collective, who was that very fall shooting a film that would be released a year later as Stranger Than Paradise—and Alisa Solomon, who now directs the Arts & Culture concentration in the MA program at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

I first joined PAJ as an editorial assistant when I was fresh out of college in 1983. I proofread, typeset, and filled book orders—and, by osmosis, I absorbed some of the exciting energy that animated the downtown art scene of the period. Bonnie and Gautam became good friends, as did a few other members of the office help, among them Eszter Balint—a former member of the Squat Theatre collective, who was that very fall shooting a film that would be released a year later as Stranger Than Paradise—and Alisa Solomon, who now directs the Arts & Culture concentration in the MA program at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

A few years ago I rejoined PAJ as an assistant editor, just in time to see in PAJ‘s 40th anniversary year. Recently I had occasion to reminisce about PAJ’s early years, where the journal started and what it has become, with Bonnie Marranca, PAJ’s editor and publisher.

GEORGE HUNKA: Can you tell me about why and how the idea of PAJ was born?

BONNIE MARRANCA: There was a great explosion of different kinds of performance in New York in the 1970s—not just in traditional theatre spaces, but in dance, video, performance art, and other forms too. It was a very exciting period, and it was much more centralized than it is now. Everybody knew each other. I lived in the same building on St. Marks Place as Lee Breuer and Ruth Maleczech. Richard Foreman had a salon on Sunday afternoons in the 1970s. We saw the same people at these performances, and we saw each other at the cafés.

The kinds of criticism that were being published then, in journals like TDR, under the editorship of Michael Kirby, the main theatre journal at the time, were very descriptive rather than what you would call critical. My then-husband Gautam Dasgupta and I were in New York, finishing our doctoral work, and sitting in the Café Borgia at the corner of Bleecker and MacDougal Streets one day (it isn’t there any more) when we had the idea for a journal that would publish new forms of criticism. That commitment to criticism has really been at the forefront of PAJ.

When I joined the journal in 1983, I was struck by the salon-like atmosphere of the office: People like Maria Irene Fornes, Lee Breuer, Spalding Gray, and Wallace Shawn would wander in, take a seat on the couch in your office, drink coffee, and talk for hours. Did you expect that to happen?

Remember, that was before email. Our writers would come in and drop the text off at our offices—Susan Sontag came by to bring the intro to a volume of plays by Maria Irene Fornes; agents came, artists. They all came to deliver their articles and plays and we’d talk for a long time. I remember one particular day when Jonathan Kalb dropped by; we stopped everything and we talked a few hours. He said to us, “Is it always like this?”

I really miss that. It’s obviously different from editing alone on your computer at home. I miss not having that exchange, that kind of office culture. It wasn’t as frenetic as today. It was much slower, with more time for getting to know the writers you were working with. People weren’t as overbooked as they are today.

How is PAJ different from academic journals that cover theatre, including TDR and Yale’s Theater?

What distinguishes PAJ from most of these publications is that we publish essays in which the artwork is the primary focus, instead of some theory about art, and we cover more art forms in every issue. Also, we publish more artist’s writings than anybody else. PAJ is driven by the artist’s voice, more journalistic writing, not that of academic theory. In our current issue, PAJ 113, for example, we published Annie-B Parson’s piece about her encounter with David Bowie during rehearsals for Lazarus at New York Theatre Workshop. Linda Montano talks about caregiving as “Dad Art.” There is also a portfolio of William Kentridge’s drawings for the Met Opera Lulu. One hundred performers, writers, directors, curators, and heads of theatres contributed to our 100th issue in 2012. We publish plays in every issue; Richard Maxwell’s Isolde was in last winter’s issue.

PAJ also started publishing books in 1979. Why?

A simple reason: We couldn’t fit all the work into the journal!

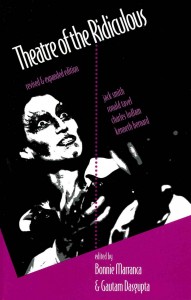

It was only around 1975 that The New York Times started to pay attention to the really new downtown scene. Our first book was Theatre of the Ridiculous, a collection of plays by Charles Ludlam, Ronald Tavel, and Kenneth Bernard.

It was only around 1975 that The New York Times started to pay attention to the really new downtown scene. Our first book was Theatre of the Ridiculous, a collection of plays by Charles Ludlam, Ronald Tavel, and Kenneth Bernard.

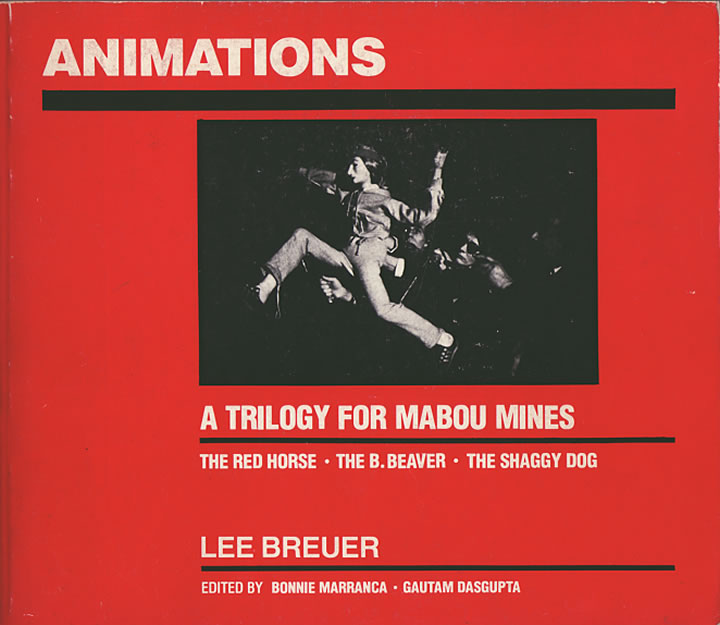

We also tried to innovate the way that play texts were published. The second book was Lee Breuer’s Animations: A Trilogy for Mabou Mines, which James Lapine designed for us in a very unusual size and typographical style. Nobody had published a book in such an innovative size and format at that time. It represented a new reconfiguration of text and image.

We also started publishing LIVE in 1979. It was more of a “zine” than a journal, really, and we covered dance, new media, clubs, performance art, and music. All seven issues of that are online now, and it’s proven to be an important source for information about that period. Sometimes the only commentary and photos from that downtown era are in the early books and in that magazine.

What are the challenges and opportunities for PAJ today? How are they different from what they were 40 years ago?

What are the challenges and opportunities for PAJ today? How are they different from what they were 40 years ago?

PAJ’s voice is in many ways an alternative to the over-academicization and over-erudition of so much scholarship. I’m still amazed when people whom I’ve never met come up to me and talk to me about PAJ! That’s because we’re covering all different generations, all different fields. We’ve crossed over and appeal to people in many other arts than theatre.

The challenges are different. People used to read a journal all the way through. Also, academics are now overly specialized. PAJ, like other journals, is now read mostly online, and people just read what pertains to their own research. They don’t read the whole journal any more. In PAJ’s earlier days, writers wrote more out of the love of something. Now people are overpublishing to pad out their CVs and promote their careers in academia.

What do you think PAJ will look like on its 50th anniversary?

Who knows? But we’re moving forward. We just redesigned the print version of the journal, but five years from now, journals will most likely be online. In the future, websites will be more active. PAJ already posts videos and audio interviews online. There’s also been an impact on the way we publish and distribute our books. Students don’t build personal libraries like they used to, so used books are returned to stores and resold, competing with the publisher’s copies at full price. This is an issue for the entire industry to face.

The questions that originally gave birth to PAJ are still the same: What is important to cover now in the journal? What should we be doing, what are we missing? I’d also like to publish a new generation of critics who are interested in something more than following current trends. I’m finding it hard to discover young critics committed to the essay form, beyond the academic critics. For sure, in the next 10 years PAJ will remain committed to its legacy and to charting new thinking in the culture of contemporary arts.