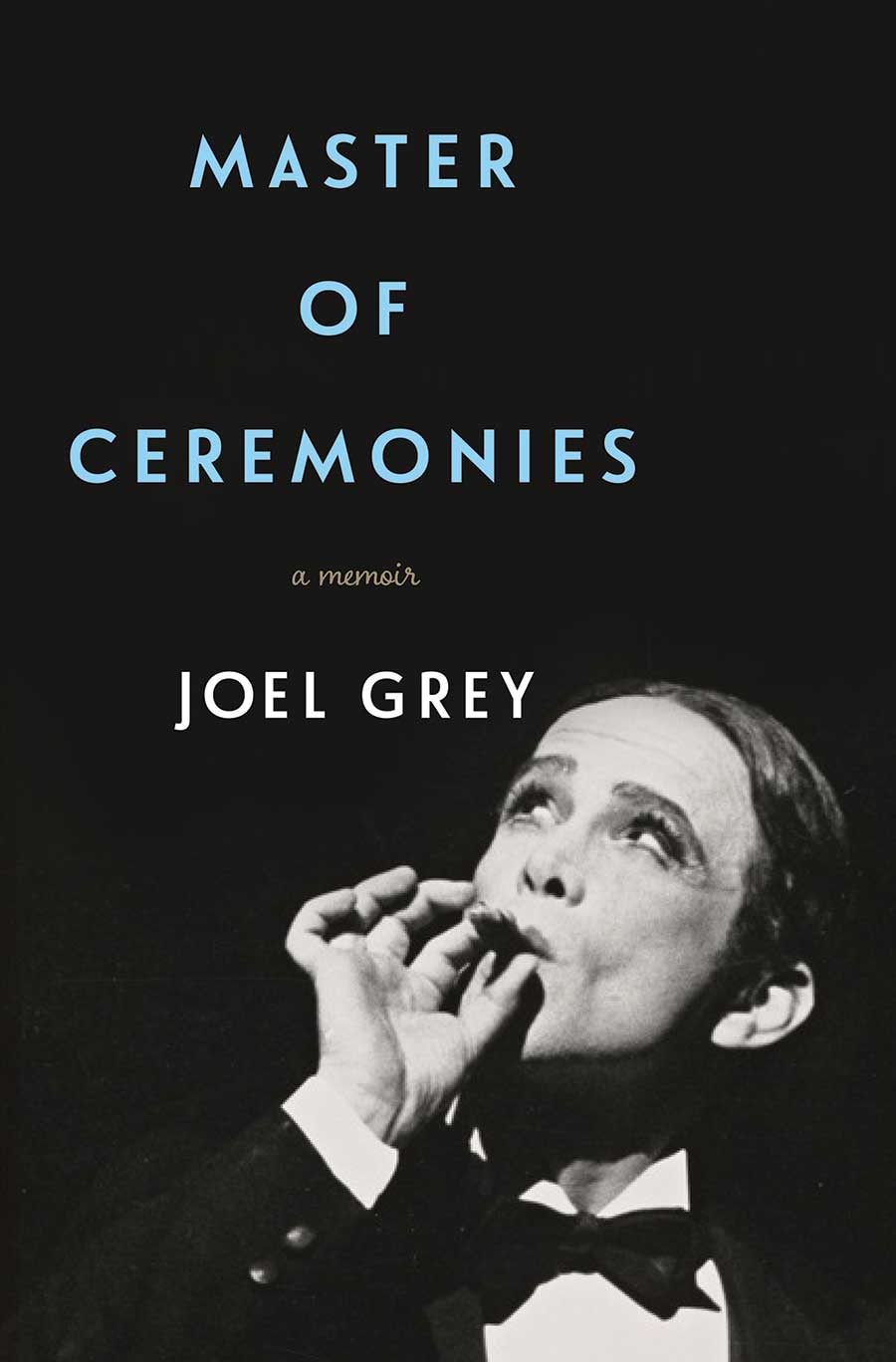

Named after a famous actor and raised in a show-business family, the very young Joel Katz delighted his mother’s mah-jongg club with everything short of a curtsy. He instinctively knew how to play roles, make people laugh, and—by his own admission—lie brilliantly to fit into any and all social arrangements. Though he probably didn’t know the meaning of the word, he was already an accomplished tummler—a genus of entertainer encompassing social director, court jester, and master of ceremonies, best represented at Catskill, N.Y.–area hotels in the middle of the last century.

Already hooked on legit theatre by the time he was 9, the youngster was nevertheless an “overnight sensation” in a satirical revue, The Borscht Capades, produced by and starring his father, Mickey Katz. By the time he was 19, Joel Grey—renamed by his agents—was a vaudeville star, stealing the best bits from Jerry Lewis, Ray Bolger, and Danny Kaye. Secretly attracted to boys before he was 10, this pint-sized bully bait was the apple of the girls’ eyes. All of these details come to light in Master of Ceremonies, the compulsively readable memoir of a born performer, a man of many masks, desires, and contradictions.

After those illustrious beginnings, what really shaped Grey’s early artistic path was a flagship regional theatre, Cleveland Play House. There he discovered a discipline and focus that would serve as the foundations of his career. Cast as the 8-year-old Pud in a production of On Borrowed Time, he was determined to be a “grown-up professional theatre actor.” It was a goal that would remain the adult Grey’s artistic touchstone.

The Play House also taught him that “the theatre is a very sexy place.” He happily noticed that women swooned over a leading man who happened to be gay and living with another man; at the age of 12 he bonded with an older teenage actor and discovered that sex with men, while regarded by some as “a disgrace,” could be connected to love. Still, based on messages he picked up in his clamorous household, it was clear that he didn’t want to be labeled faygele. His desire for an ideal family, together with the pressure to keep his homosexual life secret, would produce a lifelong identity struggle.

Perhaps that’s why, though Master of Ceremonies is replete with hilarious show-business tales, the book also vibrates with personal heartbreak. When Grey revealed to his mother he’d had an affair with a cantor, she told him, “You disgust me!”

At L.A.’s Alexander Hamilton High, Grey found himself desired by the cheerleader every jock wanted to date—and her mother as well. “More and more, the girls wanted to be around me because I could dance,” he writes. “It was what they had in mind besides dancing that I wasn’t prepared for.” But young Joel knew how to play the people pleaser. In the glow of female admiration he was compliant, wanting to please, and happy to prove his straight credentials.

In a frightening and hilarious episode straight out of a Damon Runyon story, a couple of goons came to the teenage Grey’s Chicago hotel room, accused him of fathering a child, and demanded that he pay up. Terrified and unable to confide in his parents, he called his agent, who promptly hired two beefy bodyguards to protect his client.

Yet he continued to have fraught romances with men. He told himself he was bisexual, because being gay was “out of the question.” The conflict abated when he met and immediately fell madly in love with performer Jo Wilder. Like Grey, she was an actor/singer, a liberal, and a Jew. “This is a beautiful woman,” he thought, and a wife to help build the perfect family. Desperate to get started, he proposed three weeks after their first date and coaxed her into marrying soon after.

Wilder was indeed the love of his life, but for more than 20 years he was unable to share his deepest secret. While he sometimes followed the script of a conventional husband, bullying his wife into abandoning her career to take care of their two children, Grey remembers the marriage as his happiest years.

Conflict was also at the heart of his biggest successes. “Through sheer force of will,” he writes, he made people believe he was a song-and-dance man, playing flashy Vegas hotels and even the Palladium in London. But these talents only made it harder for producers to see him as a legit actor. Leaving L.A. for New York, Grey set out to see every Broadway show and studied performances by the likes of Mary Martin, Lee J. Cobb, and Yul Brynner. The stage was the only place he wanted to be; more reliable than his own family, it made him feel safe and valued.

Like many a classic theatre memoir, Grey’s demonstrates just how perilous the profession can be for even the uniquely talented. The nadir for Grey came after a successful 1963–64 U.S. tour of Stop the World—I Want to Get Off. Raves should have led to a major project, but they didn’t. It wasn’t until 1966 that Grey found more work—in a dismal production called Mardi Gras, a showcase for Louis Armstrong, at Long Island’s Jones Beach. He seriously considered other possibilities: art gallery owner, agent, hand model, and, not surprisingly, tummler.

A call from Hal Prince about a role without a name would change everything. The Master of Ceremonies in Cabaret was the first part he’d been offered without an audition. He struggled at first; the role initially had no lines and no backstory. But a theatre artist is the sum of his influences, no matter how bad or embarrassing. Casting about for models, and fearing he’d never make the character more than a generic nightclub performer, he recalled a comic from the vaudeville circuit—a performer so desperate for attention he would do anything. One day in rehearsal Grey tried it out, groping, ogling, and clowning shamelessly. He ran offstage, humiliated by his access to such vulgarity, only to hear an ecstatic Prince tell him he’d finally found the character. The nightclub career he’d tried so hard to avoid was exactly what unlocked the Emcee. “As much as I fought against being a song-and-dance man, it was during those smoke-filled nights…that the Emcee’s utter smiling soullessness was born.”

The Emcee made him a celebrity. Bob Fosse, the director of the film Cabaret, fought to cast someone else, but the producers prevailed: Grey became only one of eight actors to win a Tony and then an Oscar for the same part (along with José Ferrer, Shirley Booth, Yul Brynner, Anne Bancroft, Rex Harrison, Paul Scofield, and Jack Albertson). His priceless account of the artistic tug-of-war with Fosse is studded with gems, such as Fosse’s admonition to follow his direction exactly: “No spontaneity, please!”

Ultimately it was theatre rather than film that suited Grey’s soul. It had become the welcoming family he’d always wanted. His own family had begun to fall apart. Though he’d expended considerable energy trying not to be gay, he eventually revealed the secret to his wife, which led to the marriage’s end in 1982, after 24 years. Grey was devastated. He was free, yet for a long time uninterested in gay relationships. He was also disturbed by the terrible plague that was killing so many men.

Three years later the personal and professional converged. At a performance of The Normal Heart at NYC’s Public Theater, Grey found playwright Larry Kramer at intermission and told him he’d do anything to have a chance to be in the play. When lead actor Brad Davis took ill with AIDS, Grey took over. Of this new journey of discovery he writes eloquently: “The first moment I truly recognized a part of myself as homosexual didn’t happen on an analyst’s couch, during affairs with men, or after my divorce. It happened onstage.”

On the page, as onstage, Grey—with the help of coauthor Rebecca Paley (not listed on the cover)—turns out to be an honest, incisive, witty, and elegant entertainer, a tummler of the highest order.

Though he had to learn the language by rote, Joel Grey borrowed heavily from that child of the Yiddish theatre, the Borscht Belt circuit. As a teenage vaudevillian whose act needed to be good clean fun, he sang the famous high-velocity ode to the homeland, “Rumania, Rumania.” Grey could easily have gone into the family business of Jewish revues. There was Yiddish theatre in his hometown of Cleveland, and Dad, who started out as a clarinetist, was renowned as a comedian. But the Lower East Side of New York, not Cleveland, was ground zero for the American Yiddish theatre, and it had already passed its zenith when Grey was a child.

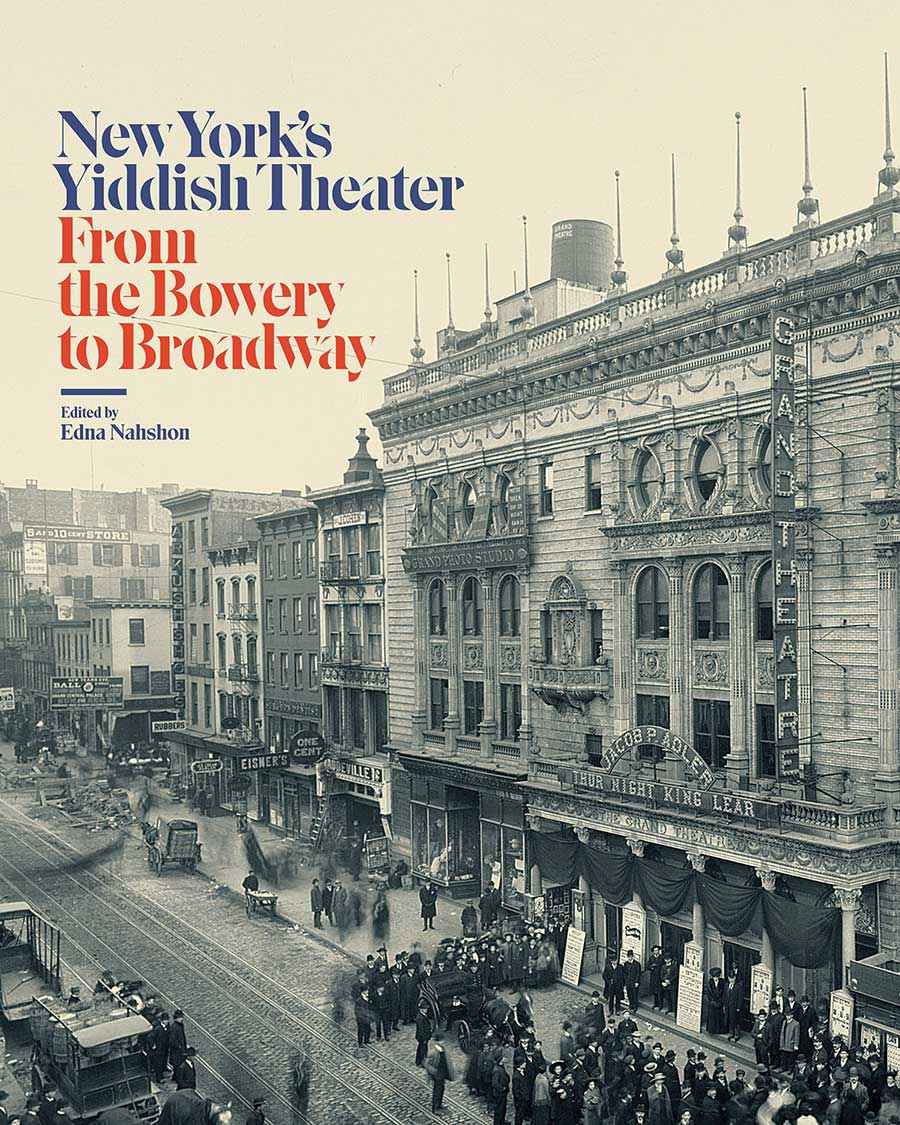

The Yiddish theatre’s soul was always a divided one. In the 1800s, it offered mostly comfort food for recent immigrants. Literary critic Irving Howe once described it as “a theatre of vivid trash and raw talent, innocent of art…superbly alive and full of claptrap.” But as Edna Nahshon writes in New York’s Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway, young Jewish intellectuals yearned for more elevated fare, and by the early 20th century, Yiddish theatre encompassed a prodigious

From the Bowery to Broadway,”

edited by Edna Nahshon. Columbia University Press, New York, 2016. 328 pp., $39.99 cloth.

range of work including vaudeville, folk musicals, original plays, adaptations of Shakespeare, Lope de Vega, Goethe, and Schiller—even a Yiddish translation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Sophisticated design work was practiced by a Russian emigré and modernist who would become one of the great American set designers, Boris Aronson.

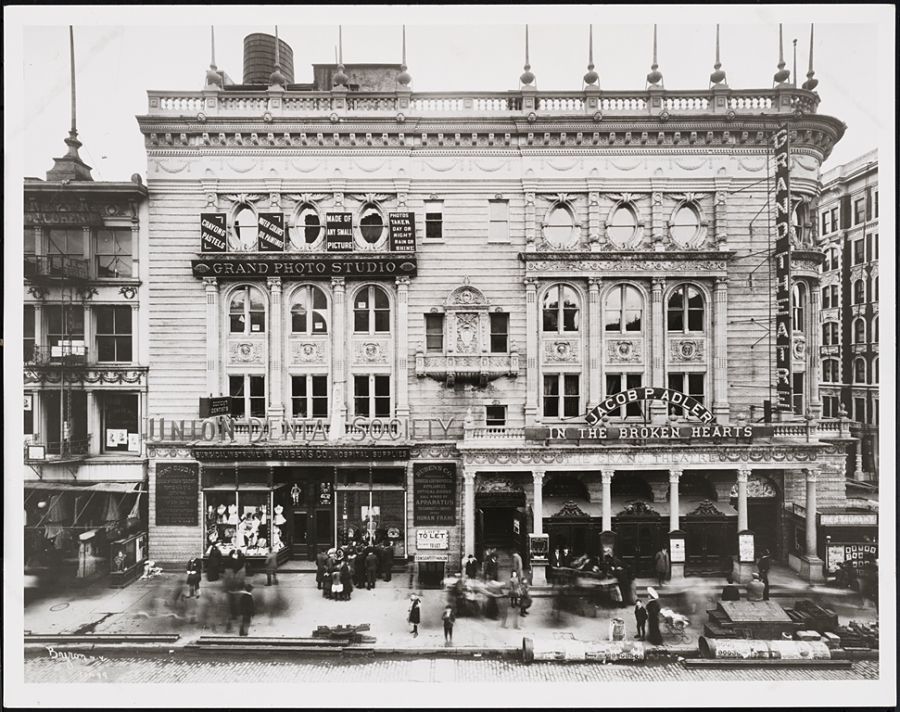

Among the form’s more serious artists was the tall, handsome, magisterial Jacob Adler. Reverently referred to as “the great eagle” (from his name in Yiddish), Adler played Shylock and The Jewish King Lear; he was considered, along with Henry Irving, one of the great Shakespearean interpreters of the age. Such was Adler’s stature that 50,000 people walked in his funeral procession (seen in an extraordinary photograph in Nahshon’s book). The cortege stopped at each Yiddish venue, then, at graveside, “as the first shovelful of earth was cast upon his coffin, a wail rose from the crowd of mourners: ‘The king is dead!’” Adler lived on through seven of his children and their own Yiddish theatre venture in 1930. For her part, Stella Adler got her start in Yiddish theatre at age 4.

A mostly sober collection of informative essays by respected academics, New York’s Yiddish Theater lacks the narrative sweep of Howe’s account but stands out especially for its remarkable photographs. In fact, the book serves as the catalogue of a current exhibit of the Museum of the City of New York’s remarkable collection of posters, photographs, drawings, and costumes and the archives of YIVO Institute of Jewish Research. Judging from the book, the exhibit is not to be missed by anyone interested in the history of New York theatre.

In her entertaining chapter on the Borscht Belt, Nahshon cites Mel Brooks’s experience as a lowly “pool tummler.” Every day in summer Brooks would enter the pool area wearing a heavy alpaca coat and derby and carrying two suitcases filled with rocks. He would then walk off the diving board shouting, “Business is terrible!” and sink to the bottom of the pool. “The audience would almost let you drown for that laugh.”

At the end of the chapter in question appears a photograph of dancing cowboys and cowgirls; in front of them in full Western regalia appears a hearty, mustachioed man. He is probably singing “Haim Afen Range,” a Yiddish parody of “Home on the Range.” The number’s author and performer, its master of ceremonies, is none other than Joel Grey’s father, Mickey Katz.

A former artistic director of Cleveland Play House, Michael Bloom is a freelance director and the author of Thinking Like a Director.