NEW YORK CITY: B.D. Wong would like to make it clear, in case it’s not already: White actors should not be playing Asian roles. “You can’t win when you have the yellowface on. You can’t win when you take the yellowface off,” said the Tony-winning actor in a keynote speech on Monday, May 2. “You’re in the wrong part!” The crowd cheered.

That in a nutshell is an apt way to sum up Beyond Orientalism, a three-hour event hosted on at Fordham University by Asian American Arts Alliance, Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC), Theatre Communications Group, and the Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts. The event sought to discuss the practices of yellowface, brownface, appropriation, and racial erasure in the American theatre and culture more broadly.

It kicked off with Wong’s speech, in which one of his key examples was the tale of making the 2007 television movie Marco Polo. Wong played a slave and Kublai Khan was played by…Irish-American actor Brian Dennehy. Wong’s speech brought home that white actors are still the default in casting, even when the role is non-white, and actors of color are relegated to playing side characters or stereotypes. Wong said he’d love for the shoe to be on the other foot, in a sense: “I would love to play a white person.”

The evening’s forum marked the launch of a national initiative to address the harmful effects of yellowface and brownface in U.S. theatre, with similar events planned for six cities and the creation of an online community.

The New York forum was spurred by the controversy last year surrounding the mostly white production of The Mikado announced, then swiftly cancelled by the New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players (NYGASP). In the months since, the forum has taken on a broader resonance. While NYGASP’s The Mikado and similar traditional productions of that musical were decried for their use of yellowface (the practice of white actors playing Asian characters, makeup or not), the practice remains rampant, particularly in film. Most recently, Scarlett Johansson and Tilda Swinton received fire for playing Asian characters in the upcoming films Ghost in the Shell and Doctor Strange, respectively.

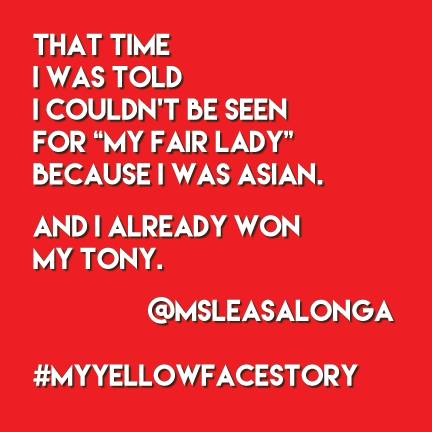

Meanwhile on social media, Asian-American theatre artists have shared stories of professional microaggressions under the hashtag #MyYellowfaceStory. Among them was Tony winner Lea Salonga:

This erasure of ethnic faces can be quantified in numbers. At Beyond Orientalism, after Wong’s speech, AAPAC presented the latest version of its annual report, “Ethnic Representation on New York City Stages.” The report broke down the racial makeup of actors hired in 2014–15, both on Broadway and in 16 Off-Broadway houses. While the numbers of actors of color hired were the highest yet recorded, at 30 percent of all available roles, the numbers are still underwhelming: African-American actors were cast in 17 percent of all roles, Latino actors in 3 percent, Asian American actors in 9 percent, and all other marginalized groups (including disabled actors) comprised less than 1 percent.

By contrast, Caucasian actors filled 70 percent of all roles, even though in New York City, non-Hispanic whites make up just 33 percent of the population. And just 10.2 percent of all roles were cast without regard to race (what the study calls “nontraditionally cast”), down from 11.2 percent in 2013–14. Those numbers have remained stagnant over the nine years of data collection by AAPAC.

“Asian-Americans were the least likely to be nontraditionally cast,” said actor and AAPAC member Pun Bandhu. “They were the least likely to ‘transcend’ their race. Perhaps there’s a connection between that and our invisibility and all the yellowface that continues to happen.”

Following the AAPAC presentation came a panel discussion. The nine-member panel included a mix of artistic directors, including Mia Katigbak of National Asian American Theatre Company, Neil Pepe of Atlantic Theater Company, and Jim Nicola of New York Theatre Workshop, as well as New York Times and Guardian theatre critic Alexis Soloski and director Nelson Eusebio. The first big question of the evening, asked by the moderator, artEquity’s Carmen Morgan, was: How do you reinvent classic that is racially problematic?

The first answer came, appropriately enough, from NYGASP executive director David Wannen. He admitted that last year’s controversy was both a shock to the system and a learning experience. The company has assembled an all-new creative team, he reported, including Asian-American artists, to reimagine a Mikado that is more inclusive and that can be embraced by all audiences, not just white ones.

“Theatre is a living organism,” Wannen said. “By reimagining The Mikado, you actually create a safer place for actors of Asian descent, and all actors of all ethnicities, to embrace and find that The Mikado is something that they can enjoy performing, and that they can tell the story of.”

But what about new work, Morgan wondered. What is the line between artistic freedom and cultural appropriation? Responded Victory Gardens artistic director Chay Yew, “Are you stealing beautifully? Some of the best artists steal.” Artists can write about experiences different from their own, he said, but research and respect is paramount. “We do borrow as artists. I think the question then becomes: Are you borrowing intelligently? Are you stealing thoughtfully? Are you coopting these things and making them into something else?”

It was not just the panelists who gave their input. The audience was also given microphones to share thoughts on how to combat the practice of yellowface and brownface. A point that was brought up multiple times was the need for outside—i.e., non-Asian—allies to help amplify the message. Though in his speech Wong cautioned that this shouldn’t be put in terms of a “white savior” narrative, he lauded the affirmation that white allies can bring.

One such ally was Michael Robertson, managing director of the Lark, who called on more white artists to step up (though the forum was primarily attended by Asian artists). “I think it’s really incumbent on the white folks in the room to decide what you’re gonna do, who you’re gonna talk to, how we’re gonna educate ourselves, how we’re creating awareness, how we’re talking to other white folks about these issues,” he said. “It’s incumbent on us to actually make the ecosystem healthier. We cannot depend on people of color anymore to be doing the fight. People cannot just fight on their own. We have to step forward and realize that we always have blind spots.”

To which Morgan responded, “We do need white folks to claim this and speak to your people!”

Indeed, one big takeway from the evening was that the fight against Orientalism and cultural appropriation needs to make allies and connections so that it is seen less as an us-versus-them problem than as a problem that affects all artists and needs a collective solution. The event’s program contained seven pointers for audience members interested in advancing race equity, among them being: teaching works by Asian-American writers, purchasing tickets to shows by or featuring Asian-American artists, and speaking up whenever racial appropriation is present.

Perhaps the evening’s loudest applause greeted playwright and panelist Lloyd Suh, who put a human face on the issue. “[Cultural appropriation] is not theoretical,” he said. “It’s not political. It’s emotionally painful. It’s humiliating and demeaning.”

Suh came under fire last year for refusing to grant the rights to his play, Jesus in India, to a college that planned to cast white actors in South Asian roles. For that decision, he received support from the artistic community, but also massive pushback. He compared the conversation around cultural appropriation, and those who defend the practice, to a question of physical assault. When white artists wonder about their freedom to culturally appropriate, what he hears is, “How many times can I punch you in the face before I’m not allowed to do that anymore?” To which Suh answered, “Why do you want to punch me in the face? Why do you want to appropriate? Who is that for? What conversation do you want to have in the world and why does it involve trying to see how much you can take from us?”

The entire event can be viewed online on HowlRound.