Most of the leading dramatic performances of this waning 2015-16 Broadway season are by actors whose mastery encompasses both stage and screen: Frank Langella in The Father, Ben Whishaw and others in The Crucible, recent Oscar winner Lupita N’yongo in Eclipsed, as well as Jessica Lange and Gabriel Byrne in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Jeff Daniels and Michelle Williams in Blackbird, and Forest Whitaker in Hughie.

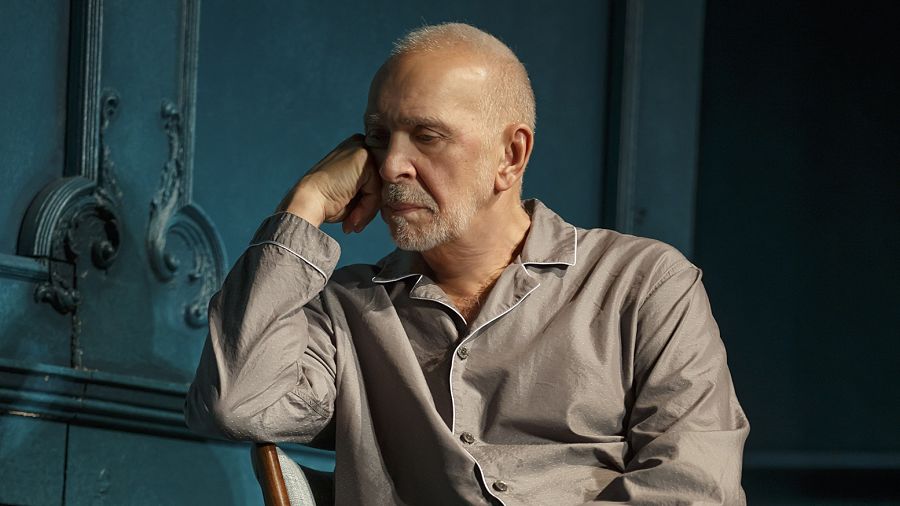

Of course, it is one thing to see actor Frank Langella give a nuanced account of the minor role of Gabriel, the world-weary KGB handler of U.S.-based Russian spies on the addictive hit FX television series “The Americans.” It is another entirely to sit in the darkened Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, watching Langella convert every ounce of his being into the character of Andre in the vertiginous new play The Father. As Andre devolves from a robust, haughty patriarch with transient memory lapses into a terrified man-child utterly lost in the black void of his shredded brain, it’s like hearing a full symphony, rather than a satisfying but brief solo in a chamber quintet.

We are living in what is commonly considered a golden age for television acting. Thanks to the wealth of character-driven prestige drama series, often scripted or cowritten by noted playwrights for cable networks, streaming services, and both public and commercial television networks, the case is easily made. The list of leading performers with major theatre cred vying for Emmys in recent years have included some of the artists mentioned above, as well as Liev Schreiber, Kevin Spacey, Frances McDormand, Viola Davis, and other esteemed players who are finding increasingly fulfilling work in serial roles, aired initially on home screens and digital pads.

But as much as actors of this caliber may excel onscreen, the stage still beckons to those with live theatre and duality in their creative DNA. And to see great performers shift into that distinctively peculiar, evanescent elixir of technique and transformation in real time is to experience their acting in not merely a different medium but in another psychic and existential dimension.

It may be gauche but it’s also irresistible—that shared excitement rippling through an expectant crowd of fellow humans, as we settle into cramped, over-priced seats to observe the aliveness of a “star” who has dazzled us in another medium. But the potent effects of celebrity and on-camera charisma quickly evaporate in the theatre, after that jarring little burst of applause for a celebrity entrance dies away. Shorn of that gilding, something else that’s equally or more impressive must follow.

The first gift of a performance like Langella’s in The Father is a busting out of, or in this case a stretching, of type, in a tale that is intrinsically, provocatively theatrical. Densely layered, centerpoint roles for actors in their 70s are scarce in modern hit plays written by pistol-hot young literary lions like France’s Florian Zeller. Zeller’s Le Père debuted in Paris in 2010 to acclaim, and the English translation (by Christopher Hampton) had a lauded run in London before Doug Hughes staged the premiere Broadway version with Langella filling the Lear–sized role of Andre, a failing lion in winter (it opened April 14 and runs through June 12).

Immaculately directed by Hughes, The Father is not Shakespearean, but it is a chilly, precise, mind-bending portrait of an 80-year old man whose understanding of himself and the world is breaking down as his age-related dementia worsens. At his most cogent, Andre is sardonic, impatient, self-important, and eager to blame his daughter Anne for his befuddlement. (The conflicted Anne is compassionately played, also against type, by theatre-honed Steppenwolf member Kathryn Erbe, longtime costar of TV’s “Law and Order: Criminal Intent.”)

With Pinter-piquant dialogue and a constantly morphing living room set, an array of short scenes reflect Andre’s mounting disorientation as the particulars of his world splinter and jumble. Whose Paris flat does he live in? Is Anne married to someone? Is her husband plotting against Andre? Has someone stolen Andre’s watch? His artwork? His wits?

On film, the camera tends to fasten closely on actor’s expertly lit face to gauge emotion. Onstage, the entire body is exposed and intelligible. The ability to use this complete instrument is one of the distinguishing gifts of a performer as wholly congruent onstage as 78-year-old triple Tony honoree Langella. He uses every inch of his 6’4” frame to convey the elegance and vanity of a fading bon vivant and practiced charmer, breaking into an impromptu tap dance while flirting with a young female visitor. Gradually Andre’s frame seems to fold in on itself: A slumping weariness accompanied by facial expressions of agitation and fear sets in, as mental comprehension is stripped away—along with pride, empowerment, and a baseline of reality.

Langella’s portrayal is unflinchingly unsentimental and harrowing, and its final crumple into defenseless infantalism enormously poignant. Audience members were audibly weeping toward the end of the show—perhaps because, like me, they had witnessed the same gradual mental erosion in a relative, and felt the same welling up of grief and fear this actor induced.

On film, such a performance would be excruciating to watch in closeup. In the theatre, more intimate yet framed, it was mesmerizingly present, impossible to turn away from, comfortless and true.

In The Crucible an actor separated by age, if not ambition, from Langella is also stretching his stage muscles.

During 35-year old British actor Ben Whishaw’s fruitful TV and film career, he has often played tentative and traumatized but impassioned young men fumbling toward love with androgynous sensitivity—the poet John Keats in the Jane Campion film Bright Star, or the cynical investigative journalist Freddy in “The Hour.” or more recently the bereft recovering drug addict Danny in another superb BBC series, the episodic murder mystery “London Spy.”

But Whishaw also has a sterling theatre track record, starting with an out-of-the-box Hamlet, and those who know him only from wistful TV roles or a recurring cameo gig as the tech-nerd whiz Q in recent James Bond films may be surprised that his range extends to the meaty role of John Proctor in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible.

Known for his extreme takes on classic plays, Belgian stage director Ivo van Hove is a star himself as the imposing auteur director of a prolific string of “maximal” and “minimal” productions rattling and rocking New York and European stages. This season’s output, van Hove’s first forays on Broadway, included a commemorative Arthur Miller twofer on with a heralded The View From the Bridge last fall through February of this year and a searing The Crucible this spring (in an open run). Both have ripped away anything veiling the raw emotional surges within these allegedly “didactic” 1950s dramas.

In van Hove’s sparely dressed, gray-scaled and historically suspended Crucible, ensemble acting is emphasized, particularly in the swarming histrionics of the young girls, who terrorize Salem, Mass. with their feverish and deadly accusations of witchcraft among the townspeople. Critics have debated van Hove’s deletion of the 1692 time scheme and the insertion of eerie supernatural effects into an allegory designed to debunk mob mentality and the abuse of hocus-pocus in religion.

Also controversial was casting Whishaw as Proctor in the first place. It’s a role based on a real-life Salem farmer and innkeeper who was accused and executed for witchcraft while trying to defend his accused wife Elizabeth. The last Proctor I saw on Broadway was Liam Neeson in 2002. He perfectly fit the physically rugged, pioneer heartthrob mold of such previous John Proctors as Daniel Day-Lewis in a famed 1996 movie version.

Slightly built and tender-faced, Whishaw gives off no such macho vibe; he could easily pass for a fey adolescent. But in the theatre, alchemy can sometimes be achieved from the inside out. Aged somewhat by a beard, slicked-back hair, and sturdy vocal projection, Whishaw seems to expand his corporeal being to fit the contours of Proctor’s rage, his earthiness, his struggle to deny the sexual temptation his former lover and head witchcraft accuser Abigail (Saoirse Ronan, a 2016 Oscar nominee for the film Brooklyn, in her theatrical debut) presses upon him.

Fighting with others to save his community from religious fascism and ruin, humbled by internal guilt and disgust, and, in a harrowing prison reunion appearing in rags with his pregnant wife (the marvelous Sophie Okonedo, a previous Tony recipient), Whishaw’s Proctor emanates a heroic masculinity that is physically grounded but more about brain than brawn.

As he and others make clear, the possibilities of stage acting are wide open, rooted in physical presence but able to transcend its limitations. It is an endeavor as distinct from brilliant movie acting as hurricanes are from tornados.