Sir Antony Sher is currently playing Falstaff in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s four-play cycle “King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings,” comprising the history plays Richard II, Henry IV, Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, and Henry V, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music through May 1. It is directed by Gregory Doran, Sher’s partner and the artistic director of the RSC.

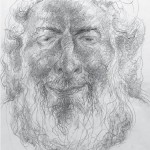

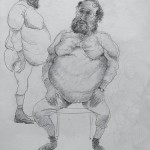

Sher’s illustrated journal about creating and playing the role in the initial RSC run in 2014 is now a Nick Hern book called Year of the Fat Knight: The Falstaff Diaries. Sher will sign copies and read from the book at Drama Book Shop in New York City on Thursday, April 28. Following are excerpts from the book, including a slideshow of Sher’s illustrations.

Tuesday 10 September

“How do you learn all those lines?”

This question is the one that the public most frequently ask of actors. We laugh about it, laugh at them for being so shallow—as though learning lines were the great mystery in acting.

Well, I’ve stopped laughing. It’s an age thing. In recent years, I’ve started doing something which I’d have disapproved of before: learning all the lines before rehearsals begin. It’s the only way now. How, as a younger actor—as one of the Dirty Duckers in Stratford in ’82, partying all night, rehearsing all day, performing in the evening—how I found time to learn lines as well, I’ve absolutely no idea.

When you’re young, it seems so straightforward: You learn the lines and that’s that. But when you’re older, you’re aware of a series of tests and obstacles ahead, each of which will put pressure on you, and the lines will often be the first casualty. So…

You have to know them alone in your room.

You have to know them when you speak them aloud with the other actors.

You have to know them when the ante is upped in the rehearsal room (such as a run-through).

You have to know them in front of the first audience at the first preview.

You have to know them in front of the critics.

You have to know them on a wet Wednesday matinee three months later, when the house is thin and you’re thinking about the shopping…

This morning, I carefully put out the things I’d need. This is in my painting studio in our London house, a rear basement room with a conservatory glass roof. I set my drawing board at an angle to the wall, and prop the script on it. I’ll learn from our A4 version, but on the shelf at my side are two published editions—the RSC and the Arden—for reference.

And it’s those published editions that are the most intimidating, those smart, scholarly paperbacks—two pairs for the two plays: I have to transfer rather a lot of the material from inside them to inside my brain.

How? Today, I’m like the most naïve member of the public. How will you learn all those lines?

I begin with the first Falstaff/Hal scene (Act One, Scene Two). I say Falstaff ’s first line: “Now Hal, what time of day is it, lad?” I say it again, and again, pacing round. I move on to his next line—“Indeed, you come near me now, Hal…”—and I practice that. Then I try the two lines together—but I’ve already forgotten the first. I start again. And so—the process is under way.

To an actor, dialogue is like food. You hold it in your mouth, you taste it. If it’s good dialogue the taste will be distinctive. If it’s Shakespeare dialogue, the taste will be Michelin-starred. Falstaff ’s dialogue is immediately delicious: You’re munching on a very rich pudding indeed, savory rather than sweet, probably not good for your health, but irresistible.

If you’re learning lines before rehearsals, you have to learn in neutral, in a way that won’t cut off the creative choices that will happen when the director and other actors are involved. So I’m speaking Falstaff in my own voice, I’m not attempting any characterization. At the same time, I can’t help noticing things about the man, and becoming drawn to certain ones. He’s well-educated, I see (he knows about Phoebus, Diana, similes, and iteration), and he’s a thief, a highwayman. A gentleman rogue, then? That breed of privileged, public-school Englishmen, who can be both monstrous and charming, both powerful and self-destructive. The kind that believe the world belongs to them. They can break the law—it’s only a bit of fun. They can drink themselves senseless—it’s what we chaps do. And they’d be totally at ease hanging out with the future King—I’ll teach him a thing or two. This country is full of men like that. Maybe that’s why Falstaff is so loved—he’s so familiar.

When I finish the session, I realize I’ve been at it for three hours. God. Time flying like when I’m writing or painting. But this is acting. Which I love less. It’s too much like hard and boring graft: doing a run of eight shows a week is a conveyor-belt job. Anyway, today’s work was pure pleasure.

Friday 18 April

It’s 7 p.m. The performance is about to start. From my dressing room, there’s a fine view across the river: a sunny evening, the big green lawns, the long blue shadows of the willows, people strolling along the paths. It’s a bank holiday—Good Friday—and Stratford is packed with visitors. It’s like the whole world is at leisure, except for us in this theatre. Part I tonight, both parts tomorrow. But I feel peaceful, I feel good.

We’ve had four-star reviews across the board. The show is deemed a success, as is my performance.

Ahead, there are exciting things: the two Live-from-Stratford broadcasts, the move to our new house, and then in July a fortnight’s holiday. A holiday? Impossible. But it’s when Two Gentlemen of Verona opens and starts to share the repertoire. Until then, we’re holding it on our own, eight times a week; until then, for me it’s just Falstaff, Falstaff, Falstaff…

Now that I’m playing it, the question is: Why is the role not considered one of those which the classical actor measures himself against? Shakespeare has mapped out the career of the (male) classical actor very sumptuously: In his youth, he can play Romeo, Hamlet, Richard II, Hal/Henry V; a few years later there’s Macbeth, Richard III, Coriolanus, Iago, Benedick, Petruchio, Leontes, Timon; and in his mature age, Lear, Prospero, Titus, Shylock, Antony, Othello. Falstaff isn’t automatically on the list. Why not? We know that Olivier turned it down—yet think of what his powers of transformation and comic inventiveness would have brought to the part. Or Gielgud—think of his wit, his melancholy dignity, the seediness he had in No Man’s Land; he would truly have been the Don Quixote of Falstaffs. Yet of that generation of actors—probably the greatest that has been—only Richardson and Wolfit played it. What a pity. And think of Scofield (I’d have paid in blood to see him do it), think of Donald Sinden, and indeed think of Ian McKellen…! Why have these actors not tackled Falstaff ? It’s a mystery to me.

Over the Tannoy: “Henry IV company, this is your beginners’ call…”

I must get ready. Go downstairs to the stage. Crawl into position in the dark. Have the bedding piled on top of me. Feel the truck move down. Then I’ll hear Alex do a big stretching yawn and jump off the bed. It’s my cue. I’ll throw back the quilts, and say:

“Now Hal, what time of day is it, lad?”

Tuesday 23 April

A day in the life of a show:

8.30 a.m. My cough is definitely real, and at its worst in the morning—awful, hacking spasms. Greg suggested I try antibiotics. Trouble is, they can cause stomach upsets. If peeing is tricky in a body suit, can you imagine diarrhea? Anyway, there’s good cause to put my woes aside. This is a great and important day: Shakespeare’s birthday—his 450th! There’s a firework display after tonight’s performance. The organizers could probably wish for better weather. It’s grey, sometimes drizzly.

10.45 a.m. Good news. Ages ago, the publisher Nick Hern got in touch and asked if I’d like to write one of my theatre journals about playing Falstaff. I said we’d have to wait and see how the shows were received. This morning, he emailed with an unequivocal yes! I’m delighted. A new focus for my mind during the long run ahead.

12.15 p.m. Greg pops home, suddenly appearing at the French windows. “Come outside,” he says excitedly. I shake my head, indicating my throat. “Oh, just for a moment!” he insists. I step onto the lawn. The bells of Trinity Church are pealing away. “They started at 11, and will go on till 3,” he says, his face alight, “for Shake- speare!” It’s called a Stedman Peal, apparently, and is reserved for only the most special occasions, like royal weddings. We picture those bell-ringers we saw in November—most of them ladies and gents of a certain age—and smile at the thought of them engaged in this Herculean task. Probably makes our matinee days seem easy.

4.45 p.m. Arriving at the stage door, I find a card from my grandnephew and theatre nut Josh. (He’s over from South Africa with his family—Randall’s daughter Heidi and her husband Ed—and saw Part I a couple of days ago.) In neat, carefully schooled handwriting, he says: “As I arrived at the theatre the adrenaline kicked in as I saw, on this momentous building, a sign that said RSC!” He calls the show “phenomenal,” says to me, “I loved the way you played your charac-ter,” and thanks us both for letting him see “a Shakespeare show at the RSC!” It’s very touching. If we could have this effect on all 12-year-olds…

7.15 p.m. The show. Part I again. There’s an unmistakable feeling of celebration in tonight’s audience. To do with Shakespeare’s birthday primarily, but the warmth extending to us, and our work. (Even my cough was better—no emergency situations at all.)

10.20 p.m. As the curtain call finishes, Greg bounds onstage and invites the audience to come outside with us for the fireworks. I race to my dressing room. Rachel takes off the wig as quickly as possible, and my dresser Rafiena helps me out of the costume and body suit, and then, leaving on most of my makeup, I jump into my civvies and go out into the night. I don’t want to miss the next bit. An extraordinary sight greets me: hundreds of people standing behind barriers, gazing up at the theatre expectantly. It’s like the end of Close Encounters. Something miraculous is about to happen.

And indeed, as a little divine sign, the drizzle that had fallen all day is no more; the heavens are clear. I find Greg in one of the control tents. There are squads of health and safety people, security people, fire officers. Greg goes onto a podium on the lawn, and, speaking into a mic, asks the crowd to bellow, “Happy Birthday, Shakespeare!” The RSC band strikes up with alarum calls—trumpets and drums—familiar from a thousand productions here, and then someone, somewhere, starts pressing buttons. The first fireworks are disappointing, half out of view, behind the building. I bite my lip: Oh no, don’t let this be feeble. But then bigger and better explosions of color begin to light up the sky above the roof—in high-leaping sprays of gold, silver, blue, and red—and in front of the theatre a huge wrought-iron portrait of Shakespeare slowly takes shape in flames, a fire drawing, while behind it an arc of tumbling white sparks gushes down the building like a waterfall. Meanwhile the RSC band has been supplanted by a soundtrack of music: now Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, now Cole Porter’s Brush Up Your Shakespeare, now Walton’s score from Olivier’s Henry V film.

I turn to Greg. We’re both grinning, both in tears. The feeling is of wonder, total wonder. Fireworks find the child in us all. Music stirs the adult. Together the mixture is intoxicating. The crowd cheers again and again. Shakespeare’s giant face is fully alight now—how pagan, we’re burning our god!—yet his expression remains as still and unreadable as ever. Though I like to think that in the church down the road, his bones are tapping along to the tunes.

11 p.m. Walking home to Avonside, I feel dazed. How wonderful to be here, in this town, on this particular night. I have just played one of drama’s classic roles in a production which Greg directed, in the theatre that he runs, and then we joined all those people to pay homage to the playwright who made it all possible, the local boy made good. It’s one of those moments when I realize I’ve been sleepwalking through my job, and then suddenly wake up, and see it for what it truly is, and it’s completely bloody amazing. Sartre said that there’s a God-shaped hole in all of us. Greg fills his with Shakespeare; the other day he said, laughing, “I’m not the director of a company, I’m the priest of a religion!”

And me? I have Falstaff inside me now—I can say it confidently at last—and that great, greedy, glorious bastard leaves no room for anything else at all.