Paula Vogel and Rebecca Taichman had to decide when it was going to start raining.

The much-mentioned “rain scene”—a pivotal moment in Sholem Asch’s 1906 moral melodrama, The God of Vengeance, and Indecent, the new Vogel play about the journey of that work and the people around it—made an emotional connection with audiences when it opened at Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, Conn., last October, the first stop of its two-theatre premiere.

Precipitation aside, it was primarily a scene of tender intimacy between two women that had special resonance for the characters in Vogel’s play—a moment of love and liberation. But Vogel and Taichman, the show’s cocreator and director, were unsure whether they’d placed the cathartic scene at the perfect, and dramatically inevitable, point in the show.

As the show moved to California’s La Jolla Playhouse in November, and even throughout the run there, the two creators continued to explore the material, rewriting some scenes, recalibrating others, and repositioning the play’s musical numbers, performed by an onstage trio of musicians deftly integrated into the production. The staging’s final stop (for the time being) is Off-Broadway’s Vineyard Theatre, where it runs April 27–June 5.

In Vogel’s elegant script and Taichman’s evocative production, the power of Asch’s original play, as well as the power of theatre, are presented in profound ways. This is a play about a play in which people are transformed in “a blink in time,” as the ownership of a piece of art transfers from playwright to audience. In Vogel’s version, the impact of The God of Vengeance lingers to their very last moments, offering deep comfort, sometimes under terrible circumstances.

Vogel remembers first reading a yellowed copy of Asch’s play in the library stacks in college in the early 1970s, just as she was coming to terms with her own sexuality, and being stunned by its portrait of a passionate lesbian romance between a 17-year-old girl and a prostitute. She was surprised to learn that the play was written in 1906 by a heterosexual married writer in Poland, who would go on to become a major author of the modern Yiddish literature movement.

The 1906 play depicts Jewish life in a naturalistic way, warts and all, in telling the story of a brothel owner striving to shelter his pure daughter from his corrupt business in the basement of his home. He tries to marry her off to a pious Talmudic scholar, but when she falls in love with one of the brothel’s prostitutes, her father’s hypocrisy is exposed, and in his rage the Torah is disavowed and desecrated. The story ends tragically.

The Polish play was a staple of the Yiddish theatre throughout Europe. Its popularity continued in the U.S. with immigrant Jewish audiences of New York City’s Lower East Side. But in 1923, when Asch’s play, translated into English, opened on Broadway at the Apollo Theatre on 42nd Street (it’s now the Ford Center for the Performing Arts), headlined by one of the biggest stars of the Yiddish theatre, Rudolph Schildkraut, as well as a young actor named Morris Carnovsky, it outraged many in the Jewish community who didn’t want this “dirty laundry” shown to a mainstream Gentile audience.

Rabbi Joseph Silverman of New York’s prestigious Temple Emanuel thundered that the play “libels the Jewish religion” and filed an official complaint that led, 15 days after opening, to the cast and producer being arrested by the vice squad, thrown in jail, and put on trial for obscenity charges. The play closed several months later.

In 2000, Taichman, then a graduate student in directing at the Yale School of Drama, was creating a thesis production called The People vs. “The God of Vengeance”, based on transcripts of the obscenity trial, interspersed with excerpts from the play. It didn’t hurt that the research material for Taichman and her grad student dramaturg, Rebecca Rugg, sat just a few blocks away: Asch’s manuscripts, memorabilia, and even the trial transcripts were housed at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

After graduation, Taichman—who shares Asch’s Polish-Jewish heritage—went on to become a prolific director, most notably for plays by Sarah Ruhl and David Adjmi. But the story surrounding the 1922 production and trial stayed with her. In 2010, she approached Vogel about joining her in revisiting the subject. Sensing the project could be a large-scale one, Vogel was interested but wary.

Vogel, the Pulitzer-winning playwright of How I Learned to Drive and a noted playwriting instructor at Brown and Yale, says that one of her frustrations as a writer is the lack of developmental support to do big ensemble pieces that need to be nurtured over several workshops and productions at several theatres before achieving their final form. She says she thinks that two of her works of such size and scope, Don Juan Comes Home From Iraq and A Civil War Christmas, have not had the chance to grow in the ways they needed.

“It’s very hard, that ‘virginity complex,’” she says, referring to artistic directors’ willingness to produce a large-scale show as a premiere but relative lack of interest in plays’ second or third iterations. But the kinds of shows Vogel’s been writing “can only be done in a very expensive way with bodies and talent and collaborators in the room. It’s not anything you can complete alone on a computer.”

For Indecent Vogel found a deep bench of support. The work was commissioned by Yale Repertory Theatre and American Revolutions: the United States History Cycle at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Supporting the evolutionary process are Yale’s Binger Center for New Theatre, Oregon Shakes, and La Jolla Playhouse. The play was also the recipient of a 2015 Edgerton Foundation New American Play Award, and has received support from the Sundance Institute in Utah and the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire.

Remarkably, Vogel, who is 64, calls this experience “an unprecedented opportunity for me in my lifetime.”

This is not the first time that The God of Vengeance has been rethought for the contemporary stage. In 2002, another Pulitzer winner, Donald Margulies, adapted the play’s action to the Lower East Side in 1923, the period when it went to Broadway. The play was produced by the Williamstown Theatre Festival in Massachusetts’s Berkshires, and staged by Gordon Edelstein, artistic director of Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven.

But Vogel and Taichman didn’t want simply to reenvision the play for contemporary audiences but rather to use the history of the play and its playwright to tell a bigger story. An improvised moment during an early workshop in Oregon was key for Vogel: Actors were asked to take off an article of clothing “and exit as if going to their death. I can’t tell you the last time I wept so hard,” she says.

That exercise led Vogel and Taichman to consider the theme “of not just the price of art but also its value to others,” says Vogel. “At the end of our lives there is that moment, not only when we see our lives passing before us but when we see the art that we made, or saw, that gave us solace. I wanted to go in that direction.

“I knew I wanted it to be more than just about the trial,” Vogel continues. But for a long period she and Taichman questioned what the work should embrace.

As it turned out, the answer was: quite a lot. It became the story of a daring and determined playwright who believed passionately in his theatrical vision—until he no longer did. It was the story of the Yiddish theatre, Jewish immigrants, and the pressure to assimilate. It was the story of the powerful forces of censorship as well as the more insidious ones of self-censorship. Indeed, Asch himself stopped authorizing productions of his play after World War II, saying he wrote it for one time and that the times had changed.

“My feeling was he just couldn’t bear to do it after what happened to Jews so horrifically,” says Taichman. “He couldn’t justify this story.” A complicated man, Asch lost many of his supporters when he began writing about Jesus and the Virgin Mary. He died in 1957 at the age of 76.

But Indecent transcends one man’s tragedy. It’s also the story of a resilient and resolute theatre company that believed in the power of art to affect audiences and to change lives. Some of the most moving scenes are among the members of the theatre company, principally the stage manager Lemml (portrayed in the current staging by Richard Topol), who represents the soul of the play and its audiences too.

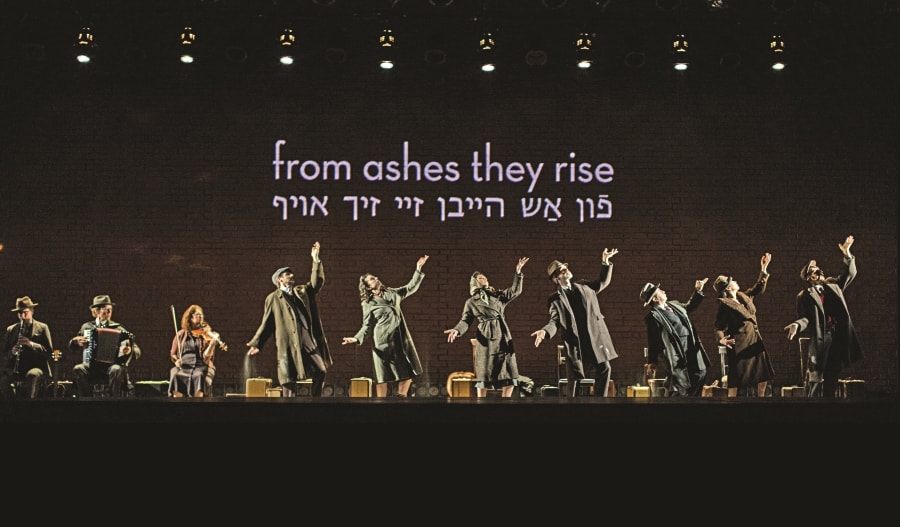

So how to present it? Taichman stages a stunning opening tableau for Indecent that has the troupe literally rising from the ashes, taking the playwright’s name to heart while evoking a sense of mortality (immortality as well). Then the narrative kicks in, with Asch first reading the play he has just written to his wife in 1906. It follows the play’s journey from a Jewish theatrical salon in Poland, where it is first derided, then finding more welcoming receptions across the stages of Europe, and finally in New York.

“It’s not a documentary,” Vogel emphasizes. “It’s an imagination of all of this.”

In Indecent, seven actors play the members of Asch’s Yiddish troupe and all other characters. Adding to the highly theatricalized storytelling are Taichman’s lyrical and image-rich direction, David Dorfman’s mesmerizing choreography and movement, and the atmosphere-setting klezmer music composed by Lisa Gutkin and Aaron Halva and performed by both with Travis W. Hendrix. Tai Yarden’s projections illuminate the Yiddish, Hebrew, and English translations and texts.

Vogel’s story doesn’t end with the court’s conclusion. Indeed, the emotional wallop of Indecent comes from the aftermath years later, in seeing the ways Asch’s play is kept alive by people who believed in it, even as far as a Lodz ghetto attic under Nazi rule.

At Yale Rep, Vogel and Taichman changed scenes again and again, reflecting not only the out-of-town tryout spirit New Haven theatre was famous for in the middle of the 20th century, but also harkening back to another era.

“What we’re doing, in a way, is replicating the Yiddish theatre process,” says Vogel, “what the troupe experienced between towns when they were working on a shoestring, creating works quickly, changing things around, with everybody knowing each other so well that they could take those shortcuts in order to grow a piece.

“The first New Haven audience let us know that there was a lot of work to be done but the shape was there,” says Vogel, “and that was a huge relief. We knew the wind was going to be at our back.”

The feedback was often personal.

“People in the audience,” says Vogel, “who were Asian, Latino/Latina said, ‘This is about my grandparents, my mother, or me; this is about immigration; this is about coming to America.’”

The 20 days between the Connecticut and California runs were filled with continual experimentation. “We both made changes in the sequencing, the musical numbers, and in the ending—and some of what we learned was that our first instincts were better,” says Vogel.

They also found the right place to put the rain scene. No spoilers, but, explains Taichman, “We didn’t want to end with death and the loss of hope.”

Work will continue, they say, in advance of the New York premiere, in a theatre, the Vineyard, with a much smaller performance space than either Yale or La Jolla. “I’m interested to see what that intimacy does and how we respond to that in the script and in the directing,” says Vogel. “We now have the ability to polish…but I still want it to be raw. I just have to get out of the way of it.”

For Vogel the play’s coming journey to lower Manhattan also has personal significance. “Now I’m going to be walking on the streets where Asch walked, where that troupe lived and worked,” she marvels. “The Vineyard is not very far from where the Yiddish Rialto was. We’re bringing the play, in a way, back to where it was birthed.”

Frank Rizzo lives in New Haven, Conn., and New York City and writes on theatre for Variety, The Hartford Courant, The New York Times, Playbill, and other publications.