When he looks back on his first time directing a Broadway musical, Scott Ellis recalls an ominous silence. It was the spring of 1993, and he was staging She Loves Me at the Criterion Center in Times Square, which had recently been renovated as the new home of the nonprofit Roundabout Theatre Company. It wasn’t just Ellis’s first musical on the Great White Way; it was also a first for Roundabout, which had made its reputation staging classic play revivals in various Off-Broadway spaces for loyal subscription audiences for a quarter-century.

The game-changing move to Broadway had been the brainchild of Todd Haimes, a Yale MBA who came on as executive director in 1983, then succeeded Roundabout founder Gene Feist as producing artistic director in 1990. The idea to do musical revivals as well as plays was also Haimes’s. Trouble is, he had not the faintest idea what he was doing.

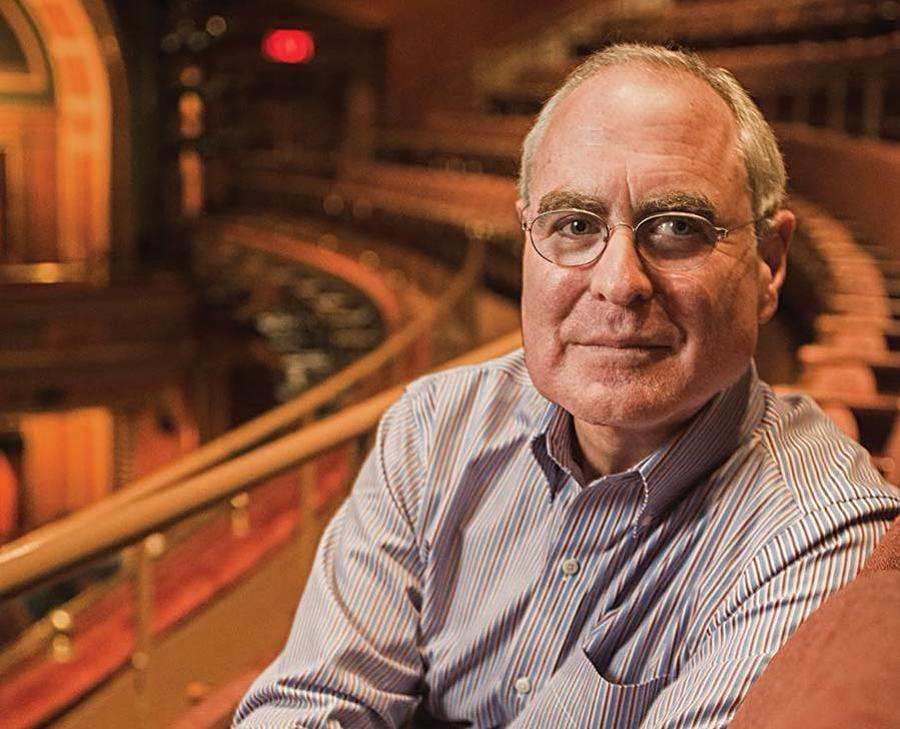

“We kind of thought that you just take a play and you add musicians and you make a musical,” said Haimes, 59, in a recent interview in his midtown office. “It didn’t work out that way. We ended up spending at least twice as much, if not three times as much, as we planned to spend. And as we approached the first preview it became clear to me that if the show was not a hit we would never do another musical, because we would have lost millions of dollars and the board would have completely freaked out.”

That’s partly why he stopped talking to his young director, Ellis, in the weeks before opening.

“For months I’d been getting constant questions—‘Why do you need this?’ ‘What is this for?’ ‘Why do you need two rehearsal rooms?’” recalled Ellis, who is staging a new production of She Loves Me for Roundabout at one of its Broadway berths, Studio 54, March 17–June 12. Then one day the questions abruptly stopped, he said. “I remember coming into the lobby, where there were tons and tons of props all over the place, and thinking, ‘Wow, this is a lot,’ but no one from his office was there to say, ‘Why do you need this?’ anymore. I think they just threw up their hands and said to themselves, ‘Now we just have to sit and pray.’”

Apparently the prayers were heard: The show was a big enough hit to have a commercial transfer, and these days Roundabout is known as much for its musical revivals as for its plays. The company, now in its 50th year, is also known for casting stars (recent examples include The Real Thing with Ewan McGregor and On the Twentieth Century with Kristin Chenoweth) in lavish stagings indistinguishable from commercial productions. Jim Carnahan, the theatre’s longtime casting director, said, “It’s amazing to me when I read reviews saying, ‘The usual lush Roundabout production values.’ I remember when it was $1.98 for sets.”

“The learning curve was very fast—they now do musicals very well,” said Ellis, who went on to direct 1776, The Boys From Syracuse, and On the Twentieth Century for Roundabout.

“Learning curve” is one way to describe Roundabout’s progress under Haimes; a series of headlong leaps into uncharted, often treacherous territory would be another. Even before making the move to Tony-eligible Broadway spaces, Haimes has always kept an eye out for the next opportunity, the next horizon, the next challenge. He claims never to have had a master plan, but he clearly has no shortage of foresight and ambition, persuading his board at several key junctures to build on hard-won success and move into new areas, even when they didn’t share his sense of urgency.

At least, that’s one way to explain why Haimes now sits at the helm of a virtual theatre empire that includes three Broadway theatres (including the American Airlines Theatre and the Stephen Sondheim), an Off-Broadway house (the Laura Pels), and another black box in the basement of the Pels, Roundabout Underground. Building and sustaining this empire has taken its toll—Haimes confessed that his workaholism probably destroyed his marriage—but he seems constitutionally incapable of pulling back. Ellis’s anecdote about the silent treatment is atypical; by most accounts, Haimes is a very accessible, hands-on manager. Even when he was battling a rare cancer of the jaw some 15 years ago, it didn’t slow his pace much. “We tried to get him to take naps, but he didn’t stop—it was really scary,” confessed Sydney Beers, the theatre’s loyal general manager.

Clearly, though he operates a nonprofit—with an operating budget of around $60 million, Roundabout is the nation’s largest not-for-profit theatre company—Haimes has no illusions about the commercial shark tank in which he operates. He seems to intuit that, like a shark, his theatre has to keep moving or it will die.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: What was your awareness of Roundabout before you took the job?

TODD HAIMES: Well, I knew that they did some decent work. I knew that they had had some Off-Broadway shows with stars, which was unusual in those days. And I knew that they had a terrible, terrible reputation in terms of business. The theatre had been in Chapter 11 since 1977. Everybody told me not to go to Roundabout because they were crooks. But, you know, I was 26 years old and I had nothing to lose, and Gene—he didn’t always necessarily know what he was doing, but he was nice and supportive. And the board was desperate because they would have been liable for the taxes, if nothing else, and the taxes were substantial. You can’t not pay taxes.

I know this sounds overly dramatic, but they had a $2.5 million dollar deficit on a $2 million dollar budget, so the cash flow was insanely horrible—much worse than I expected. I knew it was bad, but they didn’t know how bad it was. About two months after I got there, on the day of my mother’s funeral, they held a special board meeting where the board voted to close the theatre. I went home, rather despondent, but you know—it wasn’t the end of the world. I’d been there two months. The next morning the board president, Chris Yegen, called me and said, “We decided to give it another chance.” In all these years, I’ve never asked him why. I don’t know if he felt sorry for me.

The day after that a check arrived from his mother, and I’ll never forget it because it came in this little handwritten envelope, and it was one of those checks that they used to have in the old days where you see swans lying in the background, you know? It was a check for $100,000 which, to me, was like an unbelievable amount of money in 1983, with a note saying, “Hope this helps.” And the rest of the Yegen family contributed another $50,000 in the next week. With that $150,000 we were able to get the next show up and do the subscription renewal. It turned out, to make another long story short, that the theatre really was kind of a going concern that had been grossly mismanaged.

There was a core business under all the dysfunction that could be salvaged.

Yeah. They had 15,000 subscribers but were just making every mistake known to mankind.

Did they have their own space then?

They had a space that they had a lease on which expired a year later, and unfortunately they hadn’t been paying the rent. I tried to repair the relationship with the landlord, but they basically evicted us on Christmas Eve, which was nice. Then I found myself sitting on the witness stand in bankruptcy court at the age of 26 not knowing what the fuck I was doing; bankruptcy law wasn’t taught then. Now bankruptcy has become a business tool, but in those days it wasn’t like that. It was a surreal, surreal time in my life.

At what point was it your ambition to get from there to where you are now?

Never.

“Let’s get our own space, let’s move to Broadway…”

It was always “get our own space” because we had to. When we got evicted from 23rd Street, which was our main space, the theatre had a connection with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and this very nice man named Wilbur Daniels, who was the vice president there, said, “You know, we have this space on 17th and Union Square; it’s a union hall, but maybe you can convert it into a theatre.” In those days, that was a major drug zone—there were literally people with needles in their arms lying on the street. They told us, “We’re going to regentrify the neighborhood,” and we were like, “Yeah, sure.” But, you know, beggars can’t be choosers, and they gave it to us for very inexpensive rent, for five or seven years; we had to raise a million dollars in bankruptcy to renovate it into a theatre, which was a huge amount of money for us. And the board, to their credit, all signed for loans and we raised a million dollars and converted it into the Roundabout Theatre, which is now the Union Square Theatre.

Actually, they did gentrify Union Square Park right after that. The week that we opened one of our first shows, which was Uta Hagen in Mrs. Warren’s Profession, this unknown guy named Danny Meyer opened a restaurant named Union Square Café…

Wow.

It was a new concept, to have haute cuisine in a relaxed, casual atmosphere, and we used to go there for lunch every day because it was close to us. Then about six or eight weeks later, it got four stars in The New York Times and that was that. So at the end of the initial lease, we were doing perfectly fine, but the union was thinking of maybe selling the building; they said they couldn’t give us more than a year-to-year lease. I said to the board, “Look, an institution can’t run like that; we’ve got to find someplace else.” So they said, “Fine, find someplace else.” So I went looking and it just so happens that the place I found was something called the Criterion Center, which this man had built on 45th and Broadway—a 500-seat Broadway theatre that had a big cabaret space next to it. He had done a few Broadway shows and they had all been disasters, and he was just sick of it. And remember, in 1988, Times Square was still blighted. So he was willing to give us the seven-year lease on this Broadway theatre, and I thought, “Well, that would be fun.” It wasn’t because I was looking for Broadway, but it did strike me that then we’d be Tony-eligible.

The IATSE union was very cooperative in making a really fair deal because they wanted to encourage theatre, but the board was really reticent because they were afraid that nobody would come to Times Square. I told them, “We have this great lobby space and I think people will come.” So we moved there and they did come.

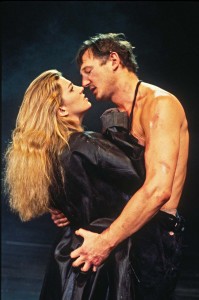

In our second season, a woman I knew but very few people in America knew named Natasha Richardson came into my office and said, “I want to do a production of Anna Christie on Broadway. Lincoln Center and Circle in the Square have already turned me down, so you’re my last chance.” Which is not a nice way of putting it, but that’s what she said. I knew Natasha’s work and I knew she was a great actress, even though she wasn’t famous in America, and I thought, What the hell? Then she said, “And I’d like this actor named Liam Neeson to play opposite me,” and I didn’t know who the hell he was because all he had done at that point was Darkman. So we offered it to Liam, and I remember getting a telegram, just a shining moment that’s etched in my mind, getting a telegram that says, “Liam Neeson accepts your offer.” And then the show happened, and to say it was the sexiest production of Anna Christie ever produced is probably the biggest understatement in history. It was legendary. It made them both famous, gave us our first Tony Award, put us on the map artistically, they fell madly in love, she left her husband, they got married.

The second seminal moment at the Criterion Center was I decided that we should be doing musical revivals, because it’s really the great indigenous American theatrical art form. In those days the only musicals that were revived were Guys and Dolls and Fiddler on the Roof, and I thought there were other great musicals that deserved revivals. A young man named Scott Ellis had just directed an Off-Broadway hit And the World Goes ’Round, which was the best revue I’d ever seen, of Kander and Ebb, with an unknown choreographer named Susan Stroman. He came to me and pitched She Loves Me and I didn’t really know it well, to be honest, but I read it and I liked it a lot and I listened to the score. We decided to do it as the first in our great American musical theatre series. The big problem was that we had never produced a musical on Broadway before, so we had no idea what we were doing. We went wildly over-budget, and there’s no way the board would have ever let us do another musical if it hadn’t succeeded. I saw it in the rehearsal hall and thought, “This is absolute perfection. It’s gonna be a hit.” It was, and we were sort of on our way with musicals.

Did producing musicals change your mission? Because once you’re doing musicals on Broadway, you’re kind of in Broadway’s main business.

Yeah, I guess so.

And now you’ve got a kind of Broadway empire.

Well, yeah, but it’s all evolution, over many years.

You didn’t sit down with a plan…

No. It was really smart that I got an MBA. I have a very good business mind, so when opportunities presented themselves, I had a good intuitive mind about which to take, which not to take. For example, it was clear to me that as Times Square was becoming gentrified, and that even though we had a couple years on our lease, we were gonna ultimately get evicted from the Criterion Center. So I went and saw [New 42nd Street president] Cora Cahan and said, “Do you have a theatre for us on 42nd Street?” And she said, “I think you can have the Selwyn,” because she was under pressure to develop theatres on 42nd Street. Disney had already committed to one and Cora was already building the children’s theatre in the Victory. So she offered it to us at a very reasonable rent, the only caveat being that we had to do the renovations.

The board—and this is typical with any board—fought me a bit on it. They said, “Well, we haven’t been evicted, what are you doing? We’re taking another theatre?” And I said, “I’m telling you we’re going to get a big rent increase, we’ve got to do something.” I convinced them, we signed the lease with Cora, and literally six months later we got the eviction notice.

The initial $7 million renovation plan turned into something like $23 million, because it was a landmark building and everything. The city was incredibly generous; I think out of that $23 million the city and the state probably gave us half of it, and the rest we just raised. And we built the American Airlines Theatre.

Then Studio 54 came into your hands after your off-site production of Cabaret in a dance club needed a new home, right?

Right. It was a little boutique production that made no sense, but it ran for six and a half years. It moved to Studio 54, which was never part of the plan but which allowed us to run so long and make money. At the end of that run, the owner of Studio 54 was going to turn it back in to a disco, which the city and the community did not want, and I didn’t want to see a Broadway theatre turned back into something else, so we used the money we had raised from Cabaret and bought it. That became our primary home for musicals. So then we had those three theatres, including the Pels Off-Broadway.

Where you managed to carve out yet another space.

About eight or nine years ago a writer named Stephen Karam submitted a play called Speech and Debate. We did a reading of it with Sarah Steele and I thought it was fucking brilliant. But I was noticing that the new plays we were doing at the Pels—because the Pels is in midtown, it’s a fairly big theatre—were getting reviewed like they were new Broadway plays; the critics were brutal on these young playwrights. I thought, We can’t do this to him; we’ve gotta find somewhere else to do it. There was this empty basement space at the Pels, and I said, “Let’s just make it into a blackbox theatre.” So for a million dollars—believe it or not, it took that much money to do it down there, even though it’s only a 62-seat theatre—we started the Roundabout Underground. We decided that the mission would be to have it be the home exclusively for young American playwrights to do their first New York production, the theory being that they’d have all the resources and sort of quote/unquote power of Roundabout without the pressure of being in a huge theatre or the nothingness of being in a loft downtown.

It probably never would have happened without Speech and Debate. And it was a big hit—it became like third most produced-play in America, and you know what happened to Stephen Karam.

What we decided to at the same time was that every time we took an Underground writer, we commissioned their second play before we did their first play so they’d feel like they had a home even if the first play wasn’t successful. So that’s begun an incredibly productive and fruitful part of the Roundabout that, again, was never part of the master plan. If you had told me that this year we would have two of the most acclaimed new plays in America by playwrights under 30 years old who came from the Underground, I would say, “You’re crazy, that’s not what we do.” You know?

You’re talking about Josh Harmon and Stephen Karam.

Yeah, they want to move Significant Other to Broadway. And Bad Jews we moved upstairs and sold out, it’s been done all over the world and he’s made a fortune, which is fabulous. And these are people who were literally 20 years old, living with their parents.

In 1990 you took over as artistic director, and you’ve been the artistic director ever since. You said you have a head for business, but obviously you also have some sort of sense of what you want to put on the stage. Or is your main job picking good directors who bring you projects?

When Gene retired I said, “Look, this whole model of artistic directors being directors is not necessarily the best model. And whether or not it’s the best model, I’m not sure it’s the only model.” I mean, the whole concept of not-for-profit theatres was 20, 30 years old at that time. Before that, for 3,000 years, they had producers, and producers were both artistic and management—Robert Whitehead and those legendary producers. You see pictures of them in the hotel rooms with Arthur Miller out of town, you know, working on a show.

So I thought, well, look, I’m not a director but I have good taste; I can be a producer. I took the title of artistic director and, actually, I still feel very reluctant about it, only because I don’t consider myself an artist. At the time I would have called myself a producer, but in the industry an artistic director meant a specific thing, and it was very important to me that the theatre knew there was a new artistic leader here. But it was considered heresy. The industry was like, “Oh my God, this manager is taking over.” Now, of course, many theatres are run by producers, but in those days it was like heresy. So I wasn’t exactly warmly welcomed.

But, anyway, I did it and the board, being indebted to me for getting them out of financial troubles, said, “Do whatever you want to do,” instead of conducting a national search and hiring somebody more qualified. So I kind of learned on the job. And over the years I’ve developed my own aesthetic. In those days Roundabout did more Shaw and Ibsen and Chekhov, and I liked that, but I was also interested in Pinter and Friel and Miller. So we started doing contemporary classics, which they had never done. And it was cool for me, because those guys were still alive and I developed real relationships with them; we became kind of their home. We did a lot of Arthur’s plays.

So first the revival thing expanded to become contemporary revivals, then expanded to become musical revivals, then it expanded to become new plays by established playwrights, then it changed more to focusing on new plays by emerging playwrights. Each time we thought we were filling a new niche that truly no one else was filling, so it’s been an evolution. None of it is part of a master plan, as opposed to a) seeing opportunities and b) trying to fill holes artistically in the industry that existed. Now I hate to be snotty, but you will notice that two years after we started the Underground, both Manhattan Theatre Club and Lincoln Center copied it. But at the time, there was no place for a 24-year-old playwright living at home who had never been produced to get produced in New York and we thought, “Well, there should be.” There’s a lot of talent there. And we’ve been very lucky with the choices that we’ve made, and a lot of credit goes to Robyn Goodman and Jill Rafson on our staff for doing that.

One thing about Manhattan Theatre Club and Lincoln Center, though: They’ll put new plays and musicals, respectively, by living writers on their Broadway stages.

Yeah, well that was always their mission. Our biggest problem is not that. Our biggest problem is that for reasons that are financial, Broadway has copied our revival model.

Tell me what you mean by that.

Okay, it’s a little convoluted. Ten years ago, if you were Daniel Craig and you wanted to do Betrayal on Broadway and you didn’t want to do a long commitment, which none of them do, you would come to Roundabout; there was no money, but it was only 11 weeks and it would get done. Then something changed with a show called The Producers; Jujamcyn started, I think smartly, saying, “Why should we give it to ticket brokers? Why don’t we just charge $400 a ticket?” Premium ticket pricing meant that it now became possible for commercial producers to say to Daniel Craig or whoever, “You can come and work and do the show for 14 or 15 weeks and we’ll pay you $50,000 or $100,000 a week,” and because they’re charging $400 a ticket, and they sell out—I don’t know if they make a fortune but they’ll still at least recoup and make a little money. So people like Scott Rudin are snapping up the rights to virtually every revival and kind of copying what was our model for 30 years.

Which makes it complicated for two reasons; one, it’s hard to get the rights to a lot of plays, but two, something else happened in the last 10 years, which is that the audience has gone from 30 percent tourist to 70 percent tourist. And tourists want to see stars. Tourists are not the audience for Roundabout or even Manhattan Theatre Club or the Atlantic Theater. If we had done The Winslow Boy eight or nine years ago with Roger Rees and gotten the reviews that we got two years ago, that show would have sold, you know, $2 million worth of tickets. Because things have changed, we did The Winslow Boy with Roger Rees a few years ago and got rave reviews and sold literally a third of the amount of tickets we would have sold in the past.

There are really two choices in terms of revivals: Either try, which is not easy, to get huge stars like Keira Knightley to come and work for no money and do really adventurous work, because that’s the only reason they’re gonna come, because nobody else would want to do Thérése Raquin. Or do more quote/unquote more commercial titles like Noises Off, where you can just get great actors and it’s a great play—but it’s hard to get the rights to those plays. So it’s become rather more complicated for us as the industry has changed, in terms of the old-fashioned revival. Not so much for the musicals, but for the plays.

You rely on more than just subscriptions, although they’ve taken a hit too.

Although we still have the largest subscription base in the city, it’s gone down from 40,000 to 30,000. And that 10,000 represents $5 million—that’s a lot of money to lose when costs keep going up. Subscriptions, which used to be something like 50 percent of our budget, is now probably 30 percent of our budget. So there is enormous pressure on fundraising and enormous pressure on single ticket sales.

Surely you’ve heard the criticism from commercial producers that being a tax-exempt nonprofit gives you an unfair advantage.

Yeah, I still don’t understand that.

Well, it’s cheaper for you, right? You get better deals with the unions; the city and state gave you money to renovate your theatre.

Well, I don’t agree with one word of what you just said. Yes, it’s true that the union deals are probably 20 percent cheaper than what they have on Broadway. But the subscribers pay half-price, we have limited engagements, we have a massive education program, and we have an Underground program which loses $250,000 at capacity every production. And we do eight shows a year. Whereas the Broadway model, some shows make $100 million, and most shows lose everything. The reality is that we have to struggle every year to raise 35 percent of our budget, which is a shitload of money, in contributions just to break even. So for commercial producers to say we have an unfair advantage I find offensive, particularly coming from a group of multi-millionaires. I’ve been here 33 years, I make $450,000 a year, and I don’t need some investment banker asshole who has $100 million telling me about my advantage. And that’s on the record.

Right, you have constraints as well as advantages. As you’ve said, you don’t charge as much, you can’t run forever…

Cabaret made $10 million. If I were a commercial producer I would get the $10 million. So that’s the choice I’ve made; I’m happy with the choice. I have no regrets, I don’t feel I’m paid unfairly, but I do resent the commercial producers saying that, because it’s so untrue it’s literally insane. Jerry Schoenfeld used to go around saying, “There’s no profit like not-for-profit.” He was famous for saying that as he was being driven around in a chauffeured limousine to his country house.

You understand why they say it, though?

Sure—every time a not-for-profit, whether it’s Roundabout or Lincoln Center or MTC, wins a Tony Award, it’s a knife in the heart of a commercial theatre producer. Because that’s the only reason they do it; they’re not in it for the art, with a few exceptions.

You’re not doing it for the Tonys.

No. I mean, last year I was very pained, not because On the Twentieth Century didn’t win, but because Kristin didn’t win; it meant a lot to me personally, because she was incredible. But there’s a reason why there are 35 people standing on that stage when they announce the winner, and it’s because they all want to call themselves Broadway producers and buy a Tony Award for $5,000.

You mentioned Robert Whitehead, but I was thinking back to people like Cheryl Crawford and the Theatre Guild, and I wondered if Roundabout and the other nonprofits on Broadway sort of are in that tradition of trying to do art in a commercial arena—to operate in a nonprofit mode but still work on the biggest platform in the country, to make a bigger impact.

It was tried once by Ellis Rabb; they had this company before the not-for-profit model days.

Do you feel like the Roundabout is part of the national, nonprofit resident theatre movement that began in the 1960s with the Guthrie, the Taper, Trinity Rep, etc., or do you feel closer to Broadway show business?

I feel much closer to the LORT than I do to the Broadway producers. I feel no affinity with them, and they feel no affinity with me, so it’s kind of mutual.

I only press the point because you’re working in their backyard.

Yeah, I’m on every committee at the Broadway League, and I listen to them sit there and fight about Tony Awards.

You don’t feel like you’re part of that world, but you’re on every committee of the League?

I thought, it’s better to be stabbed in the front than stabbed in the back.

So you’ve never had any aspirations—like, “God, this nonprofit thing is getting old, I’ve gotta cash in.”

No, I never was interested in commercial theatre. I do sometimes think I wish I had more money so that I don’t have to work until I’m 75 years old. I’m being completely honest and personal now. Not because the Roundabout didn’t pay me fairly though; it’s just there’s limitations to what they can pay, legally and morally. But I have no interest in being in the commercial theatre; I have no interest in raising money that way. I have no interest in spending five years working on one show and having it either fail or succeed depending on Ben Brantley’s review. It’s hard enough working on eight shows.

You obviously are skilled at fundraising. What’s the secret?

Well, Julia Levy, our executive director, is much better at it than I am. When you’re competing with cancer research and religion or something like that, it’s hard. I guess the two approaches are one how important historically art is to civilization—that art is civilization and will be here long after we’re gone. They’ll be seeing Death of a Salesman and maybe even Speech and Debate. And the other thing is people who love the theatre who are generous and just want to help make it happen and are just kind, generous, philanthropic people. Obviously, the Roundabout board is not a socially prestigious board like the Metropolitan Opera or the Museum of Natural History, where people are on it just to have their name on it and pay a fortune. So we have to get people who are really passionate about theatre in general and us in particular. So it’s an ongoing challenge.

I have to ask about the lack of diversity on your stages. I’ve read that when asked about that before, you said you were ashamed of that.

We are, actually. It is an issue. I’m not sure that I believe that a theatre should represent the community it’s in in the literal sense, so that if New York is 40 percent Hispanic, 40 percent of the actors should be Hispanic. Then you’re getting into literally affirmative action in the theatre. But I think we could certainly make more of an effort. Oddly enough, I do believe in nontraditional casting; we used to do more of it, and what I found in the early days is that, shockingly, it worked, even when it makes no sense. When you have a husband and a wife that’s a different color than a child that’s a different color, if they’re good actors, it works after a half hour. The problem is really pushing the directors.

We’re doing two things. We’re really going to push the directors on nontraditional casting. I do expect, for example, that The Cherry Orchard next fall will be significantly nontraditionally cast. We’re going to make a renewed push on nontraditional casting. And Sam Gold, who is our resident director, is starting an entire project to really identify and explore young writers and directors of color that he can feed into the Roundabout system, because he was feeling guilty that all his plays had just white people in them.

So I think the criticism is valid and I think we all just have to make an effort, and the directors have to be pushed a little, because they will always fall back on the actors that they are familiar with. It’s not racism; it’s just familiarity, you know.

This is where people bring up the nonprofit thing. If you’re a nonprofit, you’re a public service, and you should be held to a higher standard than commercial Broadway—that’s part of the argument.

I think that’s fair. You know, there’s nothing wrong with doing quote/unquote black plays, but it doesn’t really solve the problem, because what happens is, I’ve noticed this with us and with other theatres like Manhattan Theatre Club—they’ll do quote/unquote a black play, whether it’s August Wilson or whatever, and they’ll get a black audience, and then the next play the audience will be 100 percent white again. It doesn’t have any sort of ongoing impact, so have they achieved anything? So the ideal world is a world where the cast is multiracial, not in a forced way but in an organic way, and it’s just not an issue. It’s sort of the ideal to strive for.

I know a couple years ago, when Cabaret was brought back, there was a deficit. Has that been erased?

Yeah, I mean, we go up and down. Last year we did very well because of Cabaret and also because of we rented out the Sondheim Theatre to Beautiful, which we didn’t expect to be a hit. I just went after it because we knew we wanted to rent out the theatre for a little while after Anything Goes and I love Carole King, so when I heard it announced I just went after it like a rabid animal. I figured it would run for six months because people like Carole King’s music. We gave the producers a deal on the theatre so they went with us, and it turned out to be what it turned out to be, and so it worked out for everybody. That’s been a big help financially for us, frankly.

Though you’re not a commercial producer, it sounds like the bottom line impact of having a hit is important for you—you can’t simply rely on subscribers.

It is so expensive to do what we’re doing that if we produced The Winslow Boy and Machinal every year we would be out of business in three years. So we have to either find ways to do Thérése Raquín by getting Keira Knightley or do Old Times by getting Clive Owen or figure out something else. I think the demographic shift is worse than anything else for us because as it becomes more and more tourists, and tourists would much rather see a star in a horrible play and pay $400 than see a good production of The Winslow Boy, which means nothing to them.

So you now have so many more seats to fill than you did when you started in 1983, and you’ve got all these theatres on Broadway in an environment where it’s more hostile to what you do.

Right, so we fight the fight. We have to be much more creative and strategic and raise more money, and keep sort of nimble on our feet as the industry has changed. I mean, all these changes that you and I have just talked about, it’s an industry that’s in an enormous, I don’t know if flux is the right word—transition.

With the star-revival problem you mention, you almost helped create that model—you’re a victim of your own success in some respects.

In some ways, I guess so. I have to honestly say that the job is harder every year and not easier. Which is a little depressing after 33 years, but what the fuck?

Is there a succession plan? I mean, you seem in fine health, but it’s a question.

I think there is a short-term succession plan. For the proverbial if-I-get-hit-by-a-bus plan, somebody has already been identified who would take over at least for a couple years. I won’t say who it is, but you can make whatever obvious assumptions you want to make. Then there is the more hopeful, for me, succession plan; I say I want to retire at 70 and when I turn 68 they start doing an orderly search and do an orderly transition, you know. Hopefully it will be the latter, not me getting hit by a bus. But really the one that was most important to the board was the me-getting-hit-by-a-bus issue, because I do have cancer, so it’s not out of the question that I die and they didn’t want to be in a situation where in six months they had to find a replacement.

It’s in remission, right?

Yeah, but it’s in remission till it’s not.

You have a very supportive staff, but honestly—running three Broadway houses and two Off-Broadway spaces, I don’t know how you do it.

I work really hard and I’ll tell you, honestly, it’s taken a toll on my private life. I would say that the Roundabout probably destroyed my last marriage. It’s nobody’s fault but my own. When I say the Roundabout, I don’t mean anybody I particular. I mean my overwhelming emotional connection with the job—because it’s a very emotional job, it’s not just sitting in an office picking a play, it’s making sure that every actor is happy because what they’re not getting in money they have to get emotionally both onstage and off.

I’ve heard this about you, that you do a lot of—babysitting and hand-holding are probably the wrong terms, but you check in a lot.

We try to make the actors really feel welcome and part of that is seeing them a few times a week, at five different theatres, and saying, “How are you?” “Is there anything I can do for you?” And crying with them if they’re crying. Look, it’s an emotional business. I don’t resent them; I think what they do is awesome. I couldn’t get on a stage and do what they do, after getting a bad review particularly; I would just hide in my office. They have to get onstage and do it. But it has taken its toll on me, you know? That’s just the price of it. I didn’t think about it going into it, and I don’t know any other way to do the job.

You could’ve taken on fewer theatres, maybe.

I guess so.

But it felt to you like the Roundabout needed to grow.

I guess so. And it would be easier for me to not do the job than to not do the job 100 percent. I don’t know why that is. If tomorrow somebody said, “I’m giving you $20 million but you have to leave Roundabout,” that would be easier than if somebody said, “Just scale back and get paid the same amount of money.” I can’t do that, I just don’t know how to do that. It’s my pathology.