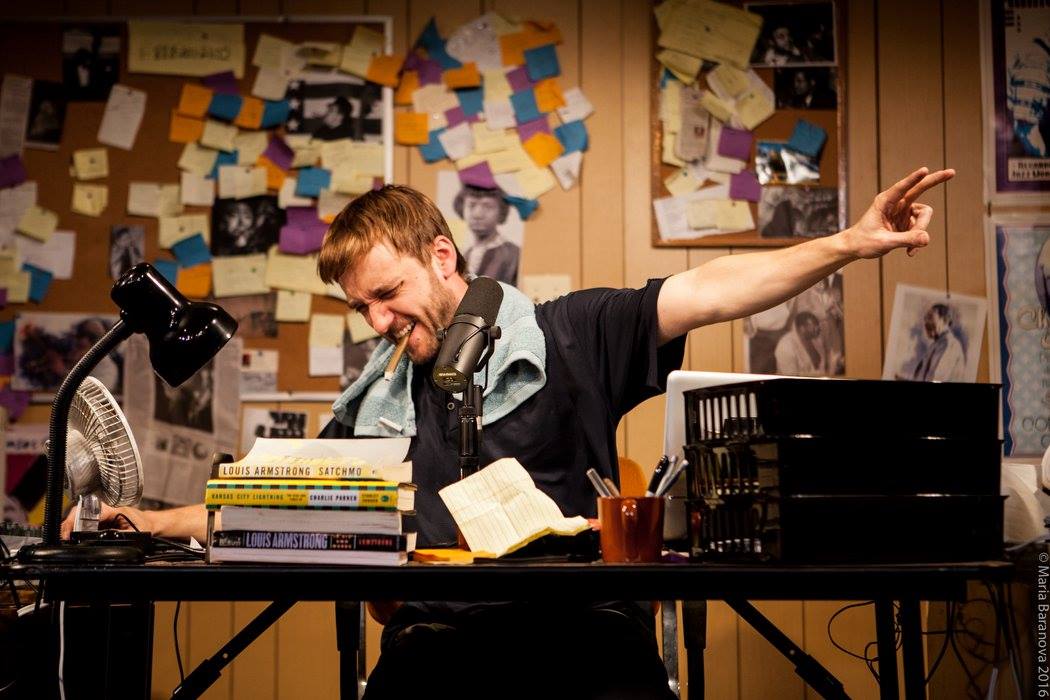

In a cubby-hole radio booth crammed to the seams with boxes, newspapers, Post-Its, and posters, the scowling hipster in dark shades spins discs and talks fervently into the wee small hours.

Who, besides a smattering of insomniac radio listeners, is awake to listen? In this case, there’s a live theatre audience sharing the room, tuned in to the latest broadcast of this Kansas City sermonizer, a jazz deejay named Ray. Feeling the spirit, impatient to spread the word, Ray regales, exhorts, and hectors listeners from his domain of sound and fury.

His chapters and verses are taken from the prophets Satchmo and Monk, Mingus and Coltrane and Simone. And he wants to baptize us all in the holy water of their music.

This jazz evangelist is the sole character in the (mostly) one-man show The Holler Sessions. But Frank Boyd, the charismatic actor who portrays Ray and created the piece (in collaboration with the New York experimental troupe the TEAM), is one of several Seattle performer-auteurs conjuring a new wave of jazz-inflected theatre.

In January, a year after its initial debut at Seattle’s On the Boards, The Holler Sessions had a successful stint at New York’s Paradise Factory, as part of P.S. 122’s Coil Festival. Soon afterward, musician and monologist Ahamefule Oluo’s extraordinary big-band performance piece Now I’m Fine, which also premiered at On the Boards in 2015, was showcased in the Under the Radar Festival at the Public Theater. (It will reemerge in Seattle this April at the Moore Theatre in Seattle.)

In a third jazz-grounded production, Emboldened, presented last July at Seattle’s Freehold Studio, playwright Reginald A. Jackson combined fact, fiction, mythology and music to riff on the shadowy life of New Orleans jazz pioneer Charles “Buddy” Bolden. Jackson is now revising the script for future production under a new title, King Bolden the First.

The style and substance of these works vary strikingly. But all creatively translate jazz, a priceless American treasure, into fresh, expressive, atypical theatre.

Boyd says he imagines Holler Sessions’s Ray as someone who, like himself, is an ardent newbie fan of the genre. “He’s not a musician,” he says. “He’s guiding both himself the audience through this thing called ‘jazz’ at the same time. I thought that might bring some fire, some light, some perspective.”

In his ensemble drama Emboldened, Jackson imagined the Storyville saga of an artist whose songs survive and musicianship is legendary—though no recordings of Bolden playing have been located. In the play, a (fictional) daughter of Bolden tries to retrace her long-lost father’s footsteps and claim her musical inheritance.

“How do you explain a figure that people don’t know so much about?” wonders actor-writer Jackson, whose earlier jazz-themed play for youth, Bud, Not Buddy, was staged at Seattle’s Book-It Repertory Theatre and Children’s Theatre Company in Minneapolis. “The daughter character became a surrogate for me as I was trying to find out who Buddy really was.”

In Now I’m Fine, Oluo (who also played trumpet for the Seattle runs of Emboldened and The Holler Sessions) is fashioning his own sui generis musical category. His show is a mesmerizing mini-symphony that brings to mind not only Duke Ellington but Spalding Gray and Sun Ra, as it merges autobiographical stories with original music for live orchestra and a shamanic singer-narrator.

Oluo insists that “jazz had nothing to do with my thought process” as he created the work over several years. “I’m not into cold fusion. I just made this music, and these stories—they worked together and became greater than the sum of their parts.”

Still, the instrumental rigor and liberating improvisation that are intrinsic to jazz are in the DNA of Now I’m Fine.

Of course, jazz and theatre have been jamming and gigging together for more than a century.

More than 100 years ago, the radical new sound, melding aspects of gospel and blues and work songs and Africa rhythms, was forged in New Orleans juke joints, social halls, and street parades by such innovating African-American musicians as Bolden, W.C. Handy, and Jelly Roll Morton.

It then drifted, taking hold in cabarets, dance halls and Vaudeville revues, before black audiences and then white, South and North. It was captured on gramophone records, starting in 1917 with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band’s landmark single “Livery Stable Blues,” and popularized nationally by the likes of Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong and others.

Theatre producers quickly recognized the dynamism and commercial potential of molten blues, laced with freewheeling swing and strut. Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s groundbreaking Shuffle Along was, in 1921, one of the first of many black musicals to thrive on Broadway. (Director-writer George C. Wolfe’s new version of Shuffle Along, featuring Audra McDonald with choreography by Savion Glover, arrives on Broadway this spring.)

From the ’20s on, African-American jazz exerted a profound influence on nearly every white “golden age” composer on Broadway, starting with Jerome Kern and George Gershwin and continuing on with Kurt Weill, Harold Arlen, and Leonard Bernstein. Images of the jazz musician as an American maverick—a purveyor of the hot and the cool, the man with the horn (or woman with the voice)—is part of our cultural iconography. And the terms “the jazz age” and “bebop” encapsulate entire eras.

Today, most theatre pieces that prominently involve jazz fit into familiar slots: crowd-pleasing musical revues that pay homage to a single composer (i.e., Fats Waller in Ain’t Misbehavin’) or to a legendary jazz scene (i.e., the heyday of Harlem’s Cotton Club, in After Midnight).

There are also the concert-biographies celebrating jazz giants (Billie Holiday at the Emerson Bar and Grill, Satchmo at the Waldorf, Dinah Was). And, sporadically, compelling fictional dramas about “the jazz life” appear, in pieces as diverse as The Connection, the Living Theatre’s seminal 1959 production (penned by Jack Gelber) about musician junkies waiting for a fix, and the watershed August Wilson drama Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, about the searing impact of racism on early black jazz artists.

The new Seattle-bred works create their own niches. “The way plays are structured now,” suggests Jackson, “you can do so much more, especially if you have live musicians. Apart from the typical standard narrative, there’s all kinds of ways to tell the stories and make the music accessible.”

Boyd, who has appeared in Elevator Repair Service’s Gatz and acted in regional theatres, says Holler Sessions was inspired by a stint he spent in Kansas City. Attending music clubs in that historical cradle of jazz, the actor awakened to a musical genre few of his Gen-X peers knew much about. “I didn’t know who Duke Ellington was until I was in my twenties,” he laments. “That’s fucked up—somebody should be held accountable for that.”

If Boyd’s show is in part a one-man crusade to turn on his peers to jazz, it is also a vivid, semi-immersive twist on a theatrical format he has misgivings about. “Honestly, to me the one-man show thing has always felt kind of dirty, theatrically. Some solo stuff is a way to show off, and do, like, 25 accents, and it’s very much about the actor. What I love about acting is listening—being affected by someone else.”

The character Ray is all about listening, and being listening to. And he’s a departure from “the cliché jazz-radio-deejay stereotype of the sleepy, all-knowing older dude, kind of pretentiously handing down information and songs,” Boyd states. “Ray’s much more like the loud, excited guys on sports radio, who get people worked up even when there’s nothing’s going on in sports.”

Boyd cites another model for the role: George Carlin, the transgressive, social critic-slash-comic whose mentor Lenny Bruce turned standup riffs into radical word-jazz.

Ray keeps up a running commentary on what’s wrong with the world and what’s right with jazz. His on-air routine also includes belting booze, doing calisthenics, chomping mini-meals—essentially living on radio. But Holler Sessions has a lot of listening, too: When Ray plays a cut by Charles Mingus or Nina Simone straight through, the stage lights darken; all there is to do is simply, only, completely listen. This is a rarity in our world of cacophonous distraction.

“For some in people this is very hard, and they get antsy,” Boyd reports. “Others love it. They wait for something to happen onstage, and eventually realize this is it, we’re going to sit here and listen to Dexter Gordon play for a minute and a half. That’s the part where I’m expecting the most of the audience—and offering the most.”

Oulu invites his audience to listen too, and laugh, but in a different key. In Now I’m Fine, the imposingly tall, sharply suited performer, whose head is closely shaven except for a signature curly topknot, leans into the microphone to recount episodes from his challenging life. He details his bout with a temporarily disfiguring and disabling skin disease. He reflects on his mixed racial heritage. He recounts a fraught encounter with his black Nigerian father, long after the man abandoned him, his sister and their white mother when Oluo was an infant.

Delivered matter-of-factly but with tremendous focus, these stories are sincere, horrifying, poignant, absurd. They can also be very funny, thanks to Oluo’s mordant wit and 10-year stint as a standup comic. “I had really horrible social anxiety when I was growing up, and people ask me, ‘How did you do standup with social anxiety?’ The idea was that I could interact with people in a social way by scripting everything I’m going to say. For a long time I didn’t have people in my personal life to work with on these things, but I could work them out in a room full of strangers, and not feel terrible or guilty about it.”

Music has been central in Oluo’s life since childhood. “My connection comes from my grandpa, who loved jazz and took me to hear the Preservation Hall Jazz Band when I was really small.” He’s played a mean trumpet since age 11, when his mother bought him the instrument from a door-to-door salesman. And he went on to earn a living gigging in Seattle and on the road in various bands. A decade ago, with three like-minded players eager to expand the boundaries of jazz, Oluo formed his current ensemble, Industrial Revelation; a few years later he began composing a song cycle with singer-songwriter okanomodé (self-described “post-soul” and “sissy-funk” performance artist) which eventually became the score for Now I’m Fine.

“I always felt the music was kind of a soundtrack for something I didn’t know about yet,” Oluo recalls. Now he calls the show an “orchestral pop opus,” a stripped-down assemblage of spoken word juxtaposed with complex and lyrical compositions played by a powerhouse 11-piece ensemble of horns and strings. Adorned with okanomode’s vocals—and his feathered and berobed griot-like presence—Now I’m Fine feels like a postmodern bildungsroman of emotional struggle and survival through art. And it swings.

Jackson’s ambitious Buddy Bolden project is tailored somewhat more conventionally, as a double-plotted detective story with music. One plotline follows the Bolden character (played by Jackson in Seattle) as he takes up the cornet and becomes a blues virtuoso and a founding father of jazz improvisation in the Storyville district of turn-of-the-century New Orleans.

Bolden’s flashy, hard-living reign as king of the Crescent City’s exploding black music scene is brief. At 30, he has a total mental breakdown, and is haunted by a monstrous phantom alter-ego. That lands him (as it did the real Bolden) in a mental asylum for the rest of his life.

Entwined in that music-suffused scenario are the struggles of Buddy’s (fictional) daughter, a plucky, pregnant and domestically abused young woman; trying to survive on her own in the Deep South, she searches for a rumored “lost” wax cylinder recording of her father, whom she has never met. Jackson’s script melds the musical cornucopia of New Orleans with the legend and lore of Bolden: the cornet blasts allegedly heard miles away, the never-found cylinder recordings, the swift rise and demise.

“You can’t do a jukebox musical on somebody who hasn’t been recorded. And there’s so much mythology around Buddy that it was a jumping off place for me—he was a real person, but almost mythical, fantastical.” In his research, Jackson came across the colorful reminiscences of Bunk Johnson, a trumpeter known for stretching the truth, who claimed to have played (and probably did) with Bolden. Johnson became another pivotal character in the play, a garrulous link to the dawning of jazz.

For the play’s jambalaya of church, honkytonk, dance and brass band music, Jackson and his Seattle director Robin Lynn Smith didn’t want require the cast to be expert musicians or convincingly “fake it” to recordings. So, as a live combo played offstage, the actors mimed and danced out the music, “channeling” it rather than imitating its production. It was an imperfect solution, but, to paraphrase Gershwin, theatre is a lot like jazz—it’s best if you improvise.

As he and other artists explore the manifold synergies between theatre and jazz, Jackson points to something else the two forms have in common: Both have often been pronounced dead, or dying.

Jackson doesn’t buy it. “There’s a Wynton Marsalis song called ‘Premature Autopsies.’ It’s about how people have been trying to put the nails in the coffin of this epic art form of jazz for a long time. And it’s about how impossible it is to kill it.”

Misha Berson was the theatre critic for the Seattle Times from 1991 to 2016. She is a regular contributor to American Theatre and the author of several books, most recently Something’s Coming, Something Good: West Side Story and the American Imagination.