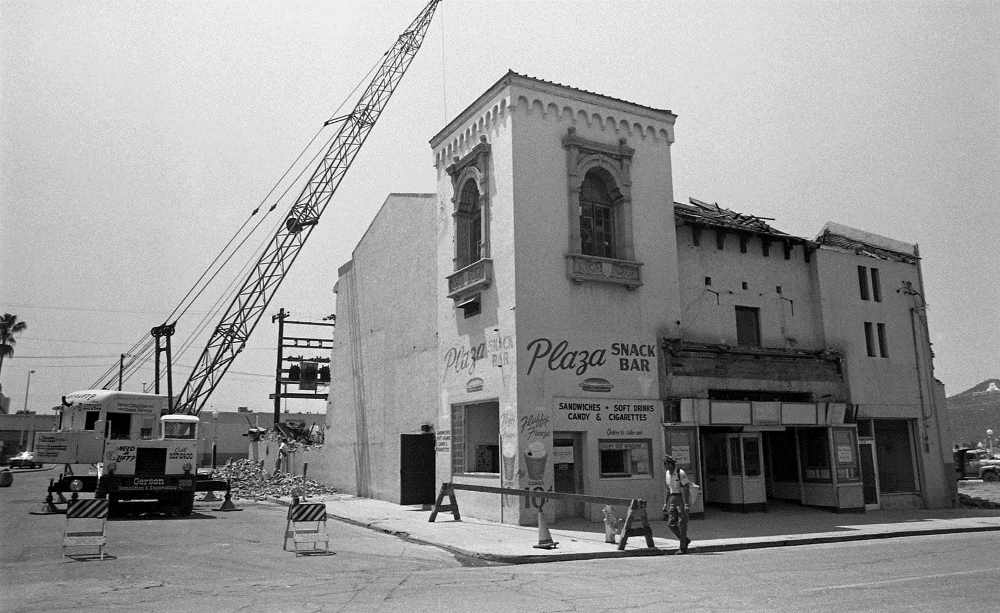

TUCSON, ARIZ.: It’s an unfortunately common story: An ethnic population moves into a neighborhood, builds it from the ground up, and makes it a cultural touchstone, only to be displaced by a tide of gentrification. In Tucson, that familiar story was retold downtown, in the area near the Tucson Convention Center. The neighborhood is the byproduct of 1960s-era urban renewal that decimated a vibrant Mexican-American neighborhood colloquially called La Calle, which means “the street” in Spanish.

“I was about 12 years old when it happened, “ recalls Jonathan Rothschild, Tucson’s mayor. “My dad worked downtown. It was where we went for everything—movies, groceries, drugstores, clothes shopping. And people lived there in the barrios all around the stores.”

This month, Borderlands Theater aims to help the city remember that erstwhile neighborhood with a show, Barrio Stories (March 3–6), helmed by the company’s new artistic director, Marc David Pinate. Intended to be the first in a series of dramatic explorations of Latino cultures inside urban centers, it will be staged site-specifically, mostly outdoors around the convention center.

Barrio Stories collects four short plays—two by Elaine Romero and two by Martín Zimmerman—alongside 20 shorter works by Virginia Grise that attendees can enjoy between the other shows. Audiences will be divided into three groups and work their way around and through the convention center, where they’ll see and hear representations of life in the old neighborhood—including oral histories from Tucsonians who used to live there.

“We want to bring the Hispanic community to theatre and Tucson citizens back to their community center,” says Pinate.

With a $50,000 grant from “A-ha! Program: Think It, Do It,” funded by the MetLife Foundation and administered by Theatre Communications Group (publisher of American Theatre), Pinate began the research process with local historian Dr. Lydia Otero, author of La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City. Local ethnographers and students from Pima College’s Upward Bound program interviewed former residents of the neighborhood. Romero, Grise, and Zimmerman were then tasked with transforming these oral histories and stories from Otero’s book into their respective dramatic works.

Mexican and Native American cultures have deep roots in southern Arizona; Otero says that native peoples may have been there 4,000 years ago. The land was part of Mexico until the 1850s, and some Mexican-American families in the former downtown neighborhood could trace their roots in Tucson back to the 1770s. (Anglo-Americans did not become the majority population in the city until the 1920s.)

In 1966, the 80-acre La Calle was razed, as part of the Pueblo Center Redevelopment Project, to make way for government offices and the convention center. “You don’t know what you have until you lose it,” says Mayor Rothschild. “Back in that time, urban renewal was considered a progressive movement and part of a real war on poverty.”

Unfortunately the main casualty of this war was the displaced Mexican-American population that had lived in the area for close to 100 years. “The most unprotected population in the urban renewal project were the people who founded our community,” says Rothschild.

Barrio Stories is about the place and the people that urban renewal forgot. Zimmerman’s short play, Slap Slap Brush…, begins with the sound of a broom on a sidewalk, as a chorus of women leads the audience into the neighborhood while meticulously cleaning their homes and the streets. His other play, One-Fifty-One follows Mexican-American homeowners being pressured into selling their homes downtown.

Romero’s play, Dirt, follows a character named “Dirt,” who leads the audiences on a poetic and metaphorical journey to explore the physical ground, once used to make the adobe bricks for homes, now covered in concrete. Her other piece, La Placita: Heart of the City, includes giant puppets and an inventive cast of characters:

LA CALLE, a young woman who disobeys her elders.

El GUAPO, an attractive young man who has rooster’s feet upon closer inspection, but he hides them behind his fancy shoes. He is revealed to be El Diablo, of course.

LA GRANDE, the oldest woman you can think of times two.

LA SOLDEDERA, a woman revolutionary from another time. Sister to Calle. Has a weapon strapped across her chest.

Grise’s pieces are installation-style events for the audience to happen upon between the fully staged plays, and they include reenactments of the oral histories collected for the production. Staging four different kinds of work in multiple locations has proved challenging for Pinate, who is a familiar with site-specific work but not works that require audiences to walk around. “The challenge will be timing three groups through the center to see the stage plays and have time for the installations,” he says.

Finally, when the plays are over, all of the groups will come together for a post-performance Pachanga!, a musical celebration with mariachi and ballet folklórico performances by local youth ensembles, plus interactive art booths to audio-record memories of the neighborhood or reactions to the plays, and get a photo taken at the portrait station.

Pinate sees creative placemaking—art based on a particular community with social goals—and good civic engagement as essential goals for theatres. Thanks to the grant and donations—including help busing 600 students in from the Tucson Unified School District—theatregoers will see the production for free or, if they’re able, for a donation.

“People don’t give much thought now to the Barrio Libre [a neighborhood in La Calle] and other barrios downtown then,” says Pinate. “Barrio Stories is especially for young Hispanics to see they had a claim on a bustling part of downtown. With a new sense of belonging, they can be part of building community here in Tucson.”

Howard Allen is an award-winning journalist and nationally ranked script analyst at ScriptDoctor.com as well as a former Equity actor and director.