A theatre is a lot like a place of worship. Everyone who ambles through its doors holds a certain set of expectations regarding roles, ceremony, relationships, and suspension of disbelief. Whether it’s Aristophanes, Shakespeare, or Mamet, much of Western theatre has held to the standards laid out by Aristotle’s Poetics: Theatre must have plot, character, music, text, and spectacle. And for the most part, that’s what audiences expect from a typical Friday evening at the theatre: a 90- to 120-minute staging of a text.

But audiences are changing, and so are their expectations. Millennials are less interested in traditional text-driven theatre and more into having an experience. In response, some regional theatres are turning at least some of their attention away from producing straight plays and toward creating one-of-a-kind experiences—and in the process, collaborating with artists and companies who’ve already made it their calling to reach these new audiences at the borders of performance and experience.

One genre that’s increasingly attracting their attention is a combination of dance and theatre, in which the story—if there is one—is told without much or any recourse to text. Take Denver Center for the Performing Arts, which recently commissioned a piece from Third Rail Projects, a dance-theatre company based in Brooklyn. Titled Sweet & Lucky, the show is part of DCPA’s Off Center program, which artistic director Kent Thompson called “a test kitchen for new work,” as well as a way to attract new audiences. “We saw collaborating with Third Rail Projects as a way to reinvigorate the new-play program.”

This synthesis of forms, which could be described as dance/theatre (not to be confused with Tanztheater or “dance theatre,” the German expressive movement of the early 20th century), is by no means a new performance genre, but its spread is rapidly blurring the lines between the two disciplines. “Dance/theatre is a fusion of art forms, and is a way to expand the way we view theatrical performance, particularly the relationship, spatially, between the performer and the audience,” Thompson said.

Elsewhere, resident theatres are now commissioning dance companies to create original works integrating movement into the DNA of a production, such as Big Dance Theater’s Man in a Case, which originally ran at Connecticut’s Hartford Stage with Mikhail Baryshnikov in 2013 before touring nationwide. These collaborations are often an exercise in cross-pollination, with theatres providing the facilities and built-in subscriber base, and the dance-theatre companies bringing in a fresh perspective—a new set of eyes with a different method for creating a performance.

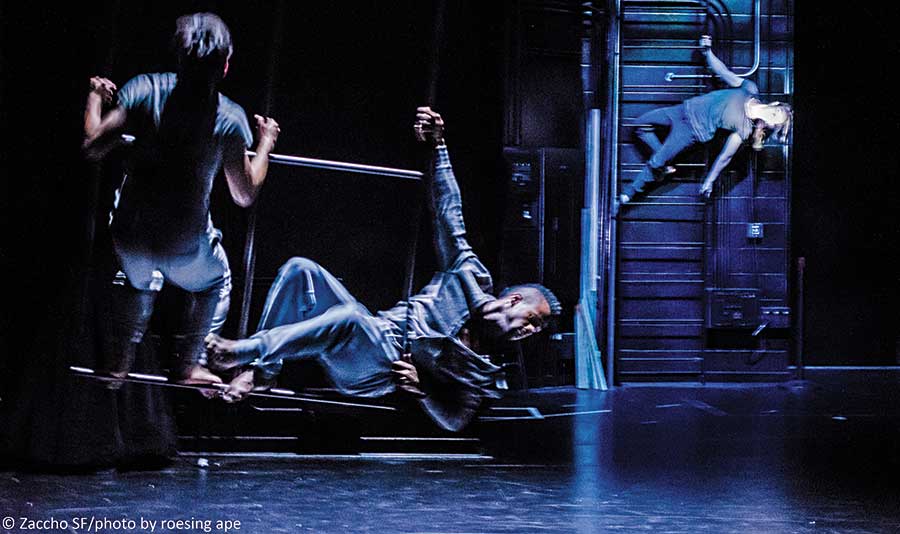

Or, to put it another way: “Dance is a movement form that often integrates other genres into its larger aesthetic, and that would include text,” explained Joanna Haigood, artistic director of Zaccho Dance Theatre in San Francisco, which is collaborating on a production for American Conservatory Theater’s (A.C.T.) next season. “Dance is dominated by the body, and, in general, can work with abstract or content-driven ideas. Dance theatre is a much more narrative form of the genre.”

Until recently, interdisciplinary work has primarily been staged by independent organizations, such as Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Theater or Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company—artistic collectives that bill themselves as dance-theatre companies. But director/choreographer Martha Clarke has often worked with resident theatres over her three-decade career, and is now ensconced in a five-year residency at New York City’s Signature Theatre. Best known for creating a sensual, swirling spectacle called The Garden of Earthly Delights, Clarke has used Signature Residency to explore the intersection of dance and theatre; in 2014’s Chéri, she put American Ballet Theatre principal dancers alongside veteran actress Amy Irving.

Her newest piece, Angel Reapers (through March 20), is cocreated with Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Alfred Uhry, and requires performers who are adept at acting, singing, and dancing. But it is emphatically not musical theatre.

“My work is multidisciplinary, but I tend to think of it as more theatre than dance,” Clarke said. “I was always interested in movement that expressed very specific emotional value, and I knew from a young age that I wanted to do storytelling, which was not popular in dance for some time.”

Clarke has been cooking up Angel Reapers with Uhry for more than a decade. The two met at a cocktail party in Connecticut and started talking about Shaker history and architecture in the region. According to the Shaker Heritage Society, the Shakers were a sect of the Quakers who formed in England in the late 1700s, later migrating to America to escape persecution.

The show takes place during the American Revolution and the text is derived from the testimonies of people who converted to the Shaker religion, which does not allow for marriage or sex. Sally Murphy plays one of the religion’s leaders, Mother Ann Lee, with the other 10 cast members dancing and singing Shaker songs a cappella throughout the show. Angel Reapers is performed in the round, so that audience members feel as if they have been dropped into late-1700s New England. The piece’s previous productions give an idea of its genre split: It’s been done at Lincoln Center Theater but also at the Joyce Theater, a New York dance space, as well as at the American Dance Festival.

“I didn’t know when I started out as a young dancer that I would move in the direction I did,” Clarke said. “The truth is, I don’t think about it. I don’t have an agenda; it’s all in the eye of the beholder. This is my second piece for the Signature, and I have one more, and having this writing residency, coming from dance initially, is a dream.”

When Brooklyn-based Third Rail Projects made a splash in 2012 with Then She Fell—which blended dance, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and immersive theatre—they attracted not just the attention of critics and audiences (the show is still running, as is their new piece, The Grand Paradise) but of DCPA’s artistic leadership. Thompson flew across the country just to see the show, which was running not in Manhattan but across the river in Williamsburg.

“I was drawn to TRP by reputation, but convinced by Then She Fell,” Thompson recalled. “Once engaged, Then She Fell created a field day for each audience member’s imagination and curiosity. As an audience member, you made up the stories to connect the dots. Beyond witness, beyond participant—you became something more.”

Then She Fell takes 15 audience members individually through a three-story building styled as a mental hospital, where they may see a pas de deux between Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell, Carroll’s real-life inspiration, or witness a monologue from the Mad Hatter. This ambulatory, multisensory approach was what Thompson was looking for. In looking to rejuvenate Off Center, he wanted to do something similar to Then She Fell, an event off-site in a cool neighborhood that would attract 18- to 35-year-olds—a demographic that Third Rail is well acquainted with. He approached the small company about a commission—and was pleasantly surprised to learn that co-artistic director Zach Morris*, who was born and raised in Denver (and coincidentally was an intern at DCPA), had been looking to bring his work to his hometown.

The two companies have been working together since last summer to hammer out the details of Sweet & Lucky, which includes finding a warehouse to lease for two to three months amid Denver’s booming commercial real estate market. Sweet & Lucky will be an exploratory experience about memory, in which audience members will enter through what looks like an antique store, into a labyrinth of distinct environments operating at different, nonlinear points in time.

Morris was partially inspired by his grandmother, whose memory has become increasingly fluid as she’s aged. “Events from the middle of the last century blur with the events of a decade ago,” explained Morris in a follow-up email. “I’ve heard my grandmother recount events that were chronologically impossible, but nonetheless true in her remembrance. I’ve witnessed my own remembrance of events become altered by the patina of age experience. So the other point of entry for me is a question what and why and how we remember.”

Sweet & Lucky will open in May and, to really bring in that under-40 crowd, there will be custom cocktails designed by a local mixologist. This is Third Rail’s first commission by a resident theatre, and the performances will feature local dancers. The piece will also contain more text than is typical for a Third Rail production.

Both companies are hoping that this initial effort will give them insights for future collaborations, not necessarily with each other. Third Rail has already started working on a piece with Albany Park Theatre Project in Chicago, and DCPA is looking to work with a Denver-based dance company called Wonderbound. For a smaller company like Third Rail, the support of a large resident theatre comes with a host of resources, including top-notch designers, access to modern facilities, and advice from the theatres’ administrative staff.

Said Morris, “We’re able to bring 15 years of exploration and fusions of forms, and DCPA is able to lend a level of infrastructure and support that we’re not used to, along with their incredible reputation.”

Fusion of forms is what drew Beatrice Basso, the director of American Conservatory Theater’s New Strands Festival, to include Zaccho Dance Theatre in the festival’s inaugural year. The festival is named after A.C.T.’s new Strand Theater space, a former silent-film movie house that reopened as a live theatre last spring. During the festival, which took place in January, invited artists had 10 days to work, then 4 days of public performances to try out new pieces, all on the way to a full production at A.C.T. in a future season.

“When I think of theatre, I incorporate dance into that definition,” Basso said. “Theatre is associated with having to have a realistic narrative in the United States, but theatre is more expansive than that.”

A.C.T. previously commissioned Haigood, Zaccho’s artistic director, to create a series of 10 short dance videos to loop on the LED screen in the theatre lobby. Haigood is a dancer and aerialist who creates site-specific work, such as her 2007 Jacob’s Pillow commission Invisible Wings, which drew on the site’s history as a stop on the Underground Railroad and was set in a barn. For the New Strands Festival, Haigood wanted to incorporate the Strand’s film history into her presentation; after development in the festival, the piece is slated become a full dance theatre performance in A.C.T.’s 2016–17 season.

“I’m interested in recreating film effects in a live performance, especially with expanding and contracting in space the way a camera zooms in and out of a scene,” Haigood said.

Making a place and its history a part of the art is a common thread in dance-theatre commissions across the country. For Heidi S. Howard, producing artistic director of Atlanta’s 7 Stages Theatre, it’s important that her audiences see the contemporary South reflected onstage, which is why she regularly commissions dance companies to perform as a part of her season planning. Howard has maintained a relationship with Sean Dorsey of Sean Dorsey Dance and has commissioned the company twice.

Howard and Dorsey met at a National Performance Network convening in 2011. Dorsey told her about a dance piece he was working on about coming-out experiences called Secret History of Love, based on oral history interviews with LGBT community elders across the country. The musical composition that accompanies the dances of Secret History includes actual interview clips woven into it; dancers also speak some of the interview text to underscore important moments onstage.

Howard first brought Secret History of Love, which has toured the U.S., to Atlanta in 2014; the performance also included a week-long residency featuring public workshops. Human rights and social justice are also throughlines of 7 Stages’s work, so Dorsey’s mission as a transgender performance artist fit perfectly. “It’s not just about merging mediums—it’s about speaking to our communities,” said Howard.

During his 7 Stages residency, Dorsey interviewed six Atlantans who experienced the AIDS epidemic in Atlanta in the ‘80s and early ’90s, and held a panel discussion about HIV/AIDS in the LGBT community for a new show, currently on tour, called The Missing Generation. To Dorsey, the addition of dialogue doesn’t defuse the dance; it makes it more accessible.

“When there is story or language used in a dance piece, it provides the audience with a window into the work,” Dorsey, said. “As a dance maker, it’s my job to create work that people can be impacted by.”

During the recent Mission Generation residency in Atlanta, his company and 7 Stages held a roundtable brunch to bridge generations in the LGBT community, as well as two workshops: a master class for intermediate to professional-level dancers and a class for local LGBT youth called “Dance Your Story” that incorporated movement and writing. Dorsey is also working on a new show called Boys in Trouble that investigates outsider perspectives of masculinity, which may lead to a third 7 Stages commission for 2017. The show will examine what masculinity looks like in communities of color and transgender communities, and among generations.

These extensive dialogues with community aren’t just important from a dramaturgical perspective; they also serve to acclimate Atlanta audiences to nontraditional forms. “Sean Dorsey is known more in the dance community than in the theatre community, which is why this is a risk,” Howard said. “Nowadays, more people attend things when they know the artists. So through the residencies and oral history interviews, we try to build the audience’s relationship with the artist.”

Clearly these new dance/theatre collaborations are expanding the performance vocabulary for audiences and theatres alike. It’s not an either/or relationship but rather/and.

“We think about both dance and theatre as different modes of expression,” Morris said. “But it’s really about which one will most articulately convey what we’re interested in exploring. Sometimes it’s more useful to talk about what you’re thinking, and sometimes it’s infinitely more visceral to see two bodies navigating a physical challenge.”

Kelundra Smith is an arts journalist based in Atlanta.

*In the print version of the story, Zach Morris was not properly introduced upon first reference.