By now, most readers of American Theatre will know about the controversy surrounding the Wooster Group’s recent production of Harold Pinter’s The Room. If not, a brief recap: The Pinter estate claims that the Wooster Group hadn’t properly secured the rights to the play, but allowed the February premiere (at Los Angeles’s REDCAT) to proceed on the condition that reviewers were not invited. A previous, unreviewed workshop production in New York last fall had proceeded without incident, but the estate nixed future presentations in Paris and New York.

This is not the first time the Wooster Group has run into trouble with a playwright or their estate; their unusual (and frequently misunderstood) relationship to text has previously, and famously, gotten them into hot water with the (then still-living) Arthur Miller and the estate of Thornton Wilder.

But this case, evidently, is different: Bruce Lazarus, the executive director of Samuel French (the estate’s U.S. licensing agent), insists that, unlike in those earlier cases, aesthetics were not at issue. According to Lazarus, the objection wasn’t to what the Wooster Group was doing with The Room but that they were acting without proper authorization.

“The Wooster Group are a renowned theatre company for which we and the Pinter estate have the greatest respect,” Lazarus told me. “The estate didn’t want The Room to come to the United States because of a possible first-class production.” (Full disclosure: I have reasons to sympathize with both sides in this dispute. I count members of the Wooster Group as friends, and Tarzana, my collaboration with the performance company Radiohole, ran recently at the Group’s space in New York, the Performing Garage. Alternately, two of my plays are published by Samuel French, and I’ve been happy with the way they handle my licensing).

The Pinter estate is under no obligation to explain its thinking, of course, regardless of how much theatregoers might disagree. But the premature closure of this production is a loss not only to the respective bodies of work of Harold Pinter and the Wooster Group, but to the theatre in general.

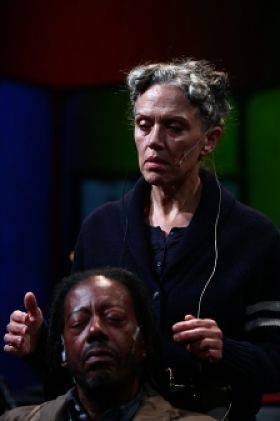

To write about any Wooster Group show is to run into the “dancing about architecture” problem—any description is reductive. Are they deconstructing classic plays and found texts? Maybe. Sometimes. Just as often, they’re paying tribute, or merely executing them skillfully. Do they have a legible lineage? Sure: There are clear antecedents in Noh theater, Beijing opera, vaudeville, New York visual and performance art of the 1970s and ’80s. But they’re equally sui generis; the whole is greater, and stranger, than the sum of its parts. Certain of their conventions have become well-known and have entered the vocabulary of downtown performance: music and dance elements that are incongruous to the point of becoming non-sequiturs; video projections; visible microphones and technical apparatus; actors being fed their lines via in-ear headphones. Yet none of this feels codified, and it avoids the baggage of a standardized aesthetic. Some of the Group’s most memorable moments are as simple, elegant, as spare as theatre can get: just human beings moving on a stage, watched by other human beings.

As director Elizabeth LeCompte will tell you, the only way to understand the Group’s aesthetic is simply to watch it, and then to watch it again—a challenging edict in an era when it’s difficult to get an audience to sit through a play even once. But this was true of me; I initially found their work bewildering, but interesting enough to see again. I remember the precise moment, two or three shows in, that it clicked. And finally, after multiple viewings of their rehearsals and performances, I’ve developed an understanding of their methodology to match my abiding appreciation of their aesthetic.

The Room at REDCAT was both unmistakably Pinter and unmistakably Wooster; unusually restrained for a Wooster Group production, it preserved all of Pinter’s sparse language, menace, and mystery. The production faithfully evoked his sense of a gloomy, damp, late-1950s Britain, still under the long shadow of World War II and facing a bleak nuclear future. The text was presented verbatim, the key differences being that it was spoken with American accents, some of it was sung, and the stage directions were narrated aloud. The effect was as if the menace had been lifted up and out of Pinter but kept present, the way a centrifuge separates plasma from blood. The mood was just as thick as it would be in an effectively realistic production, maybe even more so, but no attempt was made to depict it naturalistically (except, of course in the moments when it was; like I said, writing about this is a reductive exercise).

Even the video—often a contrapuntal or disruptive force in Wooster Group shows—remained muted and atmospheric. The play’s climactic act of violence (notably, the only onstage violence in any Pinter play) was staged minimally and elegantly. In the original, Burt (a taciturn white Briton) beats Riley (referred to as a “blind Negro” in the stage directions), presumably to death. In this version, Burt simply tilted Riley out of his chair. The gesture was purely theatrical, only thematically violent, and yet it elicited gasps from the audience, evoking racial violence in a way that no amount of Grand Guignol could.

As strong as I found the production (which was indeed reviewed, despite the estate’s wishes), I wondered why, with so many other sources available (and often used by the Group), and after so many admonishments, do they still bother to mount extant plays?

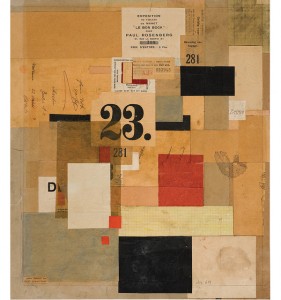

“Because I’m a masochist. Or stupid,” LeCompte told me, laughing. “When I started working with Richard [Schechner, founder of the Performance Group], we were doing collages of texts from all over, for Commune, and I was the one collecting them. And so I gravitated toward that form. I think of these things as collages. I loved Kurt Schwitters, and I loved that, whenever there was something written on [his work], I knew it really didn’t really have to do with it, but it did. [The words] brought the paintings into some other place for me than just visual collage. And the same thing with Rauschenberg, bringing huge things that didn’t match up against each other, just to see what the reverberations would be. At the same time, Spalding [Gray] knew every play, he’d read them in high school, and he always wanted to put some part that he didn’t play into his narrative about himself.”

Here we arrive at perhaps the most important insight into the Wooster Group’s methodology: They are, first and foremost, a group. While there’s no disputing that LeCompte’s creative vision is central (nor is there any argument about her singular genius), its modes of creation can only be understood in that context. Their shows are deeply personal, intimate—emergent, to use a buzzword. By contrast, most plays (including my own) are built along an assembly-line model: The playwright writes a play, if they’re lucky a theatre produces it, a director comes on board, the appropriate actors and designers are hired, and so on. Neither method is more or less correct than the other, but the Wooster Group can’t be understood using this model. Instead, they respond to the group members: their obsessions and interests, their desires as artists, the physical voices and bodies of the performers.

Like any organism, the Group is full of contradictions and resists analysis, which is one possible explanation as to why the company has been simultaneously so beloved and so misunderstood.

“Desire precedes any idea,” said Kate Valk,a frequent Wooster Group performer and director of their recent Early Shaker Spirituals. “I don’t think there’s an idea, like we’re going to say something. It starts with desire, and the idea is being revealed to us as we continue the investigation and shape the work. I think that’s why we get into so much trouble, because we let desire lead us. That’s what’s dangerous. That’s when you’re playing with fire as an artist. I don’t think we can work any other way.”

The desire behind The Room can be traced back decades. In the days of the Performance Group, Schechner had proposed a production of The Birthday Party, but LeCompte thought that the company couldn’t pull it off.

“[We were] a bunch of young people, we weren’t even actors,” she recalled. “I thought it was an incredible play, but it seemed to be culturally located in a way we couldn’t fathom at our age… But I remembered it.” In the early ’90s, she balked again, for a similar reason: “A member of the company brought in [The Room], and I thought it was too sophisticated for us. We didn’t have the facility with language to deal with it.”

But, as with all of the Group’s creative decisions, it wasn’t all up to LeCompte. Actor Scott Renderer, who played Burt, kept bringing the play in. After he left the company, LeCompte herself revived the idea. “I thought I could draw him back into the company by doing it,” she said. “I met with Scott and said, ‘I’ll do this play if you can leave your business and your life in upstate New York and do it.” But it didn’t take at first: “Even after 20 years, I didn’t think I had a feeling for it. And so I put it aside again.”

The way the Group creates theatre—the desire Valk spoke about, the antithesis of making a play to demonstrate a theory—is something akin to nest-building. It’s an assemblage that takes a little from here, a little from there, found objects and detritus, and uses them to create a home. In 2014, the company went to China, and that’s where, after nearly 40 years, they collectively found the key to understanding Harold Pinter. “We’ve always been more attracted to Asian theatre forms,” Valk told me. “The formality, the architecture, the movement.”

In China, the Group asked their tour guides for advice on what to see—not at the large state theatres doing the sorts of opera and plays already well-known in the West, but contemporary art and popular theatre. In Shanghai they discovered Pingtan, a popular Chinese theatrical form. There’s no direct Western equivalent, but it it’s akin to oral storytelling with a little bit of live music thrown in. It’s family entertainment, popular and local.

“It was back in this old theatre, behind a shopping mall,” Valk recalled. “It had a table, five chairs, a narrator who would do the sound effects. In the piece that we saw, there were two women. It was like a radio play.” In Tianjin, they discovered a popular comedic variation called crosstalk; the closest Western equivalent would be the classic vaudevillian duo (think Abbott & Costello). “We didn’t understand what they were saying,” Valk said, but “we were laughing just from the timing,” said LeCompte, completing her colleague’s thought. This is where LeCompte’s key insight took place: “‘Oh my God,’ I said. ‘Pinter. I hear Pinter here.’ I took out my notebook, I drew up the set. As soon as we got back, I had it almost finished in three or four weeks.”

Four weeks—after a gestation of almost 40 years. This is another illustration of the Group’s approach: Texts, forms, and performers swirl around like particles in a supercollider, waiting to meet and, hopefully, spark.

Also in China, the Group met a famous opera singer, semi-retired. She had become a teacher, interested in integrating Western forms into Chinese performance, and she was largely considered “undirectable.” This was intended as a supreme compliment, but it also presented her with an obvious dilemma, and spurred her to try and reinvent herself in terms of Western theatrical forms, including naturalism and expressionism. She created a solo piece about Mao’s Cultural Revolution, about a famous opera singer forced to become a washerwoman.

“The dripping pipes she hears become the sounds of an opera,” summarized Valk, “and then it transitions into her greatest moments in the opera. And then the band throws shoes at her,” she said with a laugh. “But it struck me,” continued LeCompte, “that it related to Rose’s predicament.” Played by Valk in The Room, Rose is a quintessentially Pinter character: a beleaguered housewife who chatters incessantly to warn off the abyss.

For all this, it would be a mistake to characterize The Room as external, artificial, or physical. The warmth and coldness, the humor and menace—all of them were as felt, as real and immediate as they would be in a more naturalistic staging, perhaps even more so. The work was mercurial, unpredictable, veering between theatrical styles in a way that felt neither overdetermined nor haphazard.

“It has to do with these certain kinds of rules that take you outside of yourself,” said LeCompte. “These rules force you to do things that you might not choose to do, so you see things in a way that have some distance from your own idea of what things should be. For me, it gives me a way of coming into a subject from the side, and discovering things in a different way than if I said, ‘I know what this means, now how do I make a metaphor?’ Metaphors emerge by mistake, almost, and that’s so much more pleasurable. And it keeps me working.”

Ultimately, and counterintuitively, what the Wooster Group is after is what every theatre artist has been after since time immemorial, that sine qua non of theatre: aliveness.

Jason Grote is a playwright.