In a recent essay in the Guardian, Robert Falls, the artistic director of Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, wrote of his adaptation of Robert Bolaño’s novel 2666 (at the Goodman Feb. 16-March 13) that it “is probably the last novel that one would consider adapting for the stage.”

But Falls and his collaborator Seth Bockley, with whom he cowrote and codirected the new adaptation, aren’t the first to take the plunge Bolaño’s epic five-part, 900-page book. Àlex Rigola, the head of Barcelona’s Teatre Lliure, first adapted the show in 2007, in a blood-splattered production that toured throughout Europe. (The French director Julien Gosselin, famous for adapting Michel Houellebecq’s novel The Elementary Particles, will present his own version later this year.)

For his part, Falls’s 10-year journey in bringing 2666 to the stage began in Barcelona in 2006, where he was on vacation. Around the city, he recalled in one of a pair of recent telephone conversations, Falls spotted posters of “these pink crosses in the desert,” accompanied by the mysterious numbers “2666.” The posters (likely announcing Rigola’s production) provoked Falls, who asked a local acquaintance about them and was introduced to Bolaño’s work.

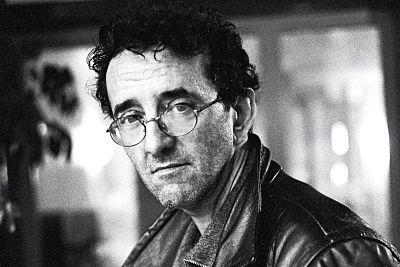

Born in Chile in 1953, Bolaño lived mainly in Mexico and, later, Spain, until his untimely death at age 50 in July 2003. Beginning his career as a poet, Bolaño found fame in his later life writing a series of novels, mixing literary culture and a critique of the right-wing politics that had driven him from his homeland (Bolaño was briefly jailed in Chile following Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup).

During his lifetime, he was most famous for his 1998 novel The Savage Detectives, but it was 2666, published in Spanish the year following his death, that made him an international publishing sensation. Consisting of five loosely interwoven novellas, the novel tells the stories of a diverse group of characters who find themselves drawn to the fictional Mexican border city of Santa Teresa in the late 1990s. Santa Teresa is thinly fictionalized version of Ciudad Juarez, and the dark heart of the novel is the very real rash of femicides in Ciudad Juarez that claimed the lives of hundreds of women over the course of a decade.

Falls first read 2666 when it was translated into English in 2008, and long before he had the resources to bring such a complex production to the stage, he began hosting private readings and working on the text in 2009 with the cast of his Bosnia-set production of King Lear.

Bockley, a playwright and director in his own right, got to know Falls when the younger artist became part of the inaugural class of the Goodman’s Playwrights Unit, a season-long residency for playwrights, in 2010. As Bockley recalled, one day Falls asked almost in passing if he’d read 2666; he hadn’t, but he had read The Savage Detectives, and anyway, as he explained, “I’d always had a love of Spanish and Latin American literature.” So he read the book and signed on as Falls’s co-adaptor and codirector, an unusual collaboration in which the pair have worked completely in tandem rather than splitting up duties.

To bring the novel’s five separate stories (and countless digressions) to the stage, Falls began with a healthy dose of self-imposed limitations.

“One sort of applies a basic structure,” Falls said. “A five-hour production became a sort of the ‘best possible constraint’ early on.” And as for the cast, who have to perform around 80 roles, “We sort of knew we wanted the cast to be 12 or 13 people. That was arrived at in advance—an experiment to divide the characters up and distribute them. That was an exercise in healthy constraint. But late in the process we found ourselves needing two additional performers, to bring the cast to about 15.”

That, in turn, gave the adaptors fresh material to play with onstage, through creative juxtapositions among actors and their multiple characters. “The most important things are the notion of echo, of duplication, of resonance between characters and the almost uncanny echoes between roles people play,” Bockley said. “The idea that a person can contain both good and evil is a major theme in the novel, and the casting of the actors and the tracking of them through the play reflects that—in surprising and sometimes even shocking ways.”

As complex as the novel’s five interlinked sections are, the first three, at least, offer a fairly clear narrative arc. In the first, “The Part About the Critics,” a quartet of young European academics meet in the 1990s over their shared love of an obscure and reclusive (and fictional) German novelist, Benno von Archimboldi. Over the years, they advance both their careers and his reputation, until he’s purportedly short-listed for the Nobel Prize. As much to escape the drama of their own torrid love lives as to finally meet their idol, they head off to Santa Teresa based on a clue that the novelist had recently headed there.

“The Part About Amalfitano” follows; it gets its name from a Chilean professor in Santa Teresa who served as the critics’ chaperone in the first section. The third part, “The Part About Fate,” introduces an African-America journalist on assignment in Santa Teresa who gets too close to the violence unfolding in the city and eventually flees with Amalfitano’s daughter.

The latter two sections veer widely off those interlinked stories, though. The fourth section, “The Part About the Crimes,” is a sprawling mystery centered on the femicides, recording 108 of them across some 250 pages, and featuring a huge cast, ranging from a crusading journalist, a good cop in a corrupt department, a small-town Texas sheriff gone rogue, even an FBI profiler. Finally, in the fifth section, “The Part About Archimboldi,” the novel goes back to the end of World War I to introduce the reclusive German novelist, following him through the Eastern Front during the Second World War, thematically linking the femicides to both the Holocaust and Stalin’s terror, and winding up with the mystery of why the aged writer heads off to Mexico in the ’90s.

The first problem the adaptors had to solve was how to move the story forward. While extended bits of the show play out as character-driven scenes, others are performed as direct address to the audience—extended monologues of “characters narrating their own stories,” as Falls put it. Each section of the novel (the adaptation preserves Bolaño’s structure) has its own feel: The first story about the academics has the tone of a lecture, in keeping with Bolaño’s narrative tone; the final section about Archimboldi is more like a “fairy tale,” as both adaptors noted, in keeping with its bizarre twists and turns (including Nazis cavorting in the castle of Dracula’s inspiration, Vlad the Impaler).

The more profound challenge Bockley and Falls faced was dealing with the countless digressions, which add thematic depth but do little to advance the story. One bit that made it in, “even though it didn’t really move the story forward,” according to Bockley, is the tangential character Edwin Johns. A fictional painter, he comes up as a minor character in the first section who produces a crisis of faith in one of the academics, an Italian named Morini. The story Morini hears is that Johns, before his first big gallery show, had—in a moment of apparent artistic inspiration—cut off his own hand to add to an assemblage. Morini, suffering from a never explained disability, is shocked that an artist would disable himself. But upon tracking the painter down in a Swiss asylum, Johns provides a devastating explanation for his action: “For money.”

In the context of Morini’s story, it causes him to despair over his life’s work (what if the reclusive Archimboldi is no better?), as well as giving context to the artistic project of the novel itself by casting doubt on art’s intentions, not to mention its capacity, to change a world in which very real problems—namely, violence in its diverse forms—are immune to the power of art.

“He’s a fascinating character and fascinating story, but not necessarily one that forwards anything,” Falls pointed out. “But there’s a rich thematic quality it has.”

Other anecdotes and tangents, however, didn’t make the cut. “Fans of the book could very easily come and go, ‘Oh, Barry Seaman was left out!’” Falls said of the difficult choices they had to make. “Both of us in early versions dealt extensively with trying to make Barry Seaman work, as an interview by Oscar Fate. And I would have loved to have been able to include Barry Seaman, but it just didn’t work.”

Seaman appears toward the beginning of the novel’s third part, as the subject of an interview by the black journalist Fate before he heads to Mexico. A former Black Panther, Seaman has reinvented himself after stints in prison as a strange sort of motivational speaker. Having written a book of all the recipes for barbecuing ribs he knows, he tours churches giving sermons mixing philosophical perspective into culinary advice. It’s one of the novels most comic sections, but also a tactic Bolaño uses to address the legacy of Civil Rights and black nationalism in the U.S. (many of the novel’s tangents provide context for the failure of various radical movements through history).

Another challenge was in balancing how to present the novel’s violence. Rigola’s production didn’t shy away from blood and brutalized bodies onstage, but Falls and Bockley took a very different tack, inspired by Bolaño’s own literary devices. The femicides in “The Part About the Crimes” are each described in their aftermath, in the detached and purely descriptive language of police reports. In fact, Bolaño based them on actual reports he received from the writer Sergio Gonzalez Rodriguez, who’s become a globally respected expert on the femicides in Juarez, who Bolaño writes into 2666 as a character.

Falls and Bockley chose to maintain this distance in their version, having these crime scene reports presented directly to the audience by a chorus of Latino female actors. In fact, it was this decision that prompted them late in production to add additional actors to the cast, to ensure a diverse group of female performers.

“We struggled with having fewer crimes described,” Falls said, “so that audiences wouldn’t become desensitized. Then we added more.”

One sound justification for more, not less crime reporting, as well as for a more diverse cast, is that Bolaño uses this multiplicity of stories to paint a patchwork portrait of the experience of globalization. Many of the victims are migrants, trying to get to the United States, or drawn to the maquiladoras, small manufacturing plants set up following NAFTA. Still others are clearly victims of the drug trade. Collectively, their experiences, recorded in the sterile notes of police reports, reveal the painful and destabilizing effects of the developing world’s relationship to the U.S. and other advanced economies.

The decision to present the femicides as a testimonial to the victims, rather than staging the violence, helps bring these issues to the fore without distracting or desensitizing. As Falls noted, “The most violent thing in our play happens 45 minutes in,” when two of the academics, caught up in a fraught love triangle, “beat the shit out of a Pakistani cab driver,” then try to convince themselves it wasn’t a hate crime.

After nearly five years of work, both Bockley and Falls know the text inside and out. And with just a week before previews, they were still debating tweaks to the text, with Falls interrupting an interview to warn Bockley they still had to talk about adding a monologue back in. But for all that, finally getting the show onstage and working with actors to bring it to life had a special magic.

“Something I’ve been looking forward to realizing for so long is an image, so iconic to the book, of Amalfitano hanging a book on a clothesline,” Bockley said. “It’s such a beautiful image in Bolaño’s book, and mysterious and poetic. It’s been in our script for so long—it’s been years we’ve been developing the script—and then to finally have the day you see an actor pinning a book to a clothesline and realize that image in three dimensions—it’s so exciting to see that happen.”