To some extent, Alan Rickman is the reason I teach Shakespeare.

When I was 13 years old, my parents took my brother and me on a summer vacation to England and Scotland. They had been saving up for the trip for years, so the pressure was on to pack everything we could into two weeks, as we wouldn’t be coming back any time soon. Part of our crowded itinerary was a trip to Stratford-on-Avon to see the Royal Shakespeare Company perform.

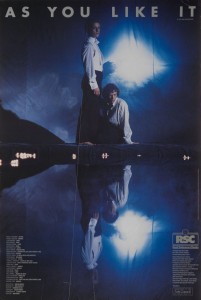

It was the first live Shakespeare I had seen. And there couldn’t have been a better way to start: As You Like It, directed by Adrian Noble. This was 1985. I would later learn that this was Noble during one of his most ambitious periods: Having served for five years as assistant director of the RSC and still three years from being promoted to director of the company, Noble had his feet under him but also had something to prove. The design was gorgeous and minimal, and to a 13-year-old’s eyes: magical. The various settings were created by an enormous white sheet which covered the ground of the stage like a blanket of snow in some scenes, and in others twisted upwards to make an impossibly tall tree suggestive of the Forest of Arden.

But it was not the awe-inspiring design that hooked me, nor was it the brilliant performances of Juliet Stevenson and Fiona Shaw as the cousin/lovers Rosalind and Celia. It was Rickman as Jaques. If you know the play, you’ll recall that in the scene before Jaques enters, the banished king and his men—“merry men,” as in tales of Robin Hood, living off the forest in boisterous jocularity—make a big deal about how funny Jaques is. And he’s funny because while everyone else in the forest has shown up for a party, this melancholy courtier always acts like he’s attending a funeral.

I’ve only ever seen this extended set-up pay off with Rickman in the role; usually the actor cannot live up to the hype. But the moment Rickman entered the stage—dressed all in black in this production, in contrast to everyone else’s “happy” white attire—he was so hilariously sad. Rickman’s Jaques was a proto-Hamlet—or perhaps Jaques is the comedy flip-side of Hamlet, since the plays were most likely composed at the same time. With his frown drawn down to his chest, Rickman spoke each word with slow, pained, perfect diction—as if his bellows-deep half-whisper were drizzling a mixture of molasses and poison over each syllable as it left his mouth. With a glance and a sigh, Rickman seemed to wither the flowers in this garden of Eden. And I loved him more than anyone else onstage, instantly.

No doubt, for a 13-year-old boy who listened to the Smiths, Jaques—the only character who bows out of the comedy’s happy-ending festivities—was relatable in that simplistic, teen-angsty way. Jaques is the one who essentially says in the end, Eeyore-style: “That’s all right. You enjoy your dance. I’ll just sit over here.” On another level, though, it was Rickman’s delivery of Jaques’ famous “All the world’s a stage” speech that blew my mind that afternoon in such a way that I have spent the rest of my life to trying to put the pieces back together again.

No doubt, for a 13-year-old boy who listened to the Smiths, Jaques—the only character who bows out of the comedy’s happy-ending festivities—was relatable in that simplistic, teen-angsty way. Jaques is the one who essentially says in the end, Eeyore-style: “That’s all right. You enjoy your dance. I’ll just sit over here.” On another level, though, it was Rickman’s delivery of Jaques’ famous “All the world’s a stage” speech that blew my mind that afternoon in such a way that I have spent the rest of my life to trying to put the pieces back together again.

After the production, I bought the play and devoured it. It was not the first Shakespeare play I read, but it was the first that I read passionately—and today one that I teach every year to my undergraduates trying to ignite that spark in others.

I know that to most people Rickman will always be Severus Snape, and if an actor has to live on in celluloid memory associated with one particular role, that’s not a bad way to go. But I will always think of Rickman as Jaques. In my office, beside my diplomas the only framed image I have is a poster of the 1985 production of As You Like It. In it, Rosalind and Orlando stare into a deep blue pool of water, another beautiful stage element of Noble’s production. Rickman is not in the photo. I’ve always thought his absence was unfortunate. Now I find his absence tragic.

Scott Proudfit is an assistant professor of English at Elon University. He performed and devised with the Actors’ Gang, the Factory Theater, and Irondale Ensemble Project, and covered New York and Los Angeles theatre as an editor for Back Stage and Back Stage West.