Disclaimer: Brian Kulick is a professor in the theatre department at Columbia University School of the Arts, where I am an MFA candidate. He has never been my professor and we have interacted only once or twice in passing. And Lynn Nottage has been my professor at Columbia, but I have not communicated with her about this essay or this issue.

Collaboration in theatre is complicated. Many have tried and many more probably will try to say what went wrong in the rehearsal process for Classic Stage Company’s Mother Courage and Her Children which led to Tonya Pinkins’s much-discussed departure from the production this week (which can be read about here, here, here, and here). Outsiders, on the basis of their past experiences, their allegiances, and in some cases their prejudices, can try to explain what went wrong in rehearsal. Only those who were in the room can really have any idea what went on there, and even their experiences are colored by perspective, history, and emotion.

But as complicated as it is to try to say what went wrong in the rehearsal room, there are some things that we can say definitively without being in the room, and some important lessons to be learned from this dispute by CSC and other theatre companies.

Though much of Pinkins’s public statement, published by Playbill, is about her experience in rehearsal and her artistic differences with Brian Kulick, the production’s director and CSC’s artistic director, her title gets at a problem that we don’t have to have been in rehearsal to understand. “Who Loses, Who Thrives,” she asks, “When White Creatives Tell Black Stories?” She suggests the hashtag #BlackPerspectivesMatter and argues that Mr. Kulick should have valued and respected her perspective as a black woman more. The fact is, of course, that since theatre is a collaborative form and the director’s role is to shape and organize the products of that collaboration, the director’s perspective (not to mention the writer’s) will almost always be as prominent as, if not much more prominent than, the perspectives of the actors. CSC’s Mother Courage is a play by a white playwright directed by a white director with a black cast, transposed from a European setting to an African one, and I think that therein lies the root of the problem.

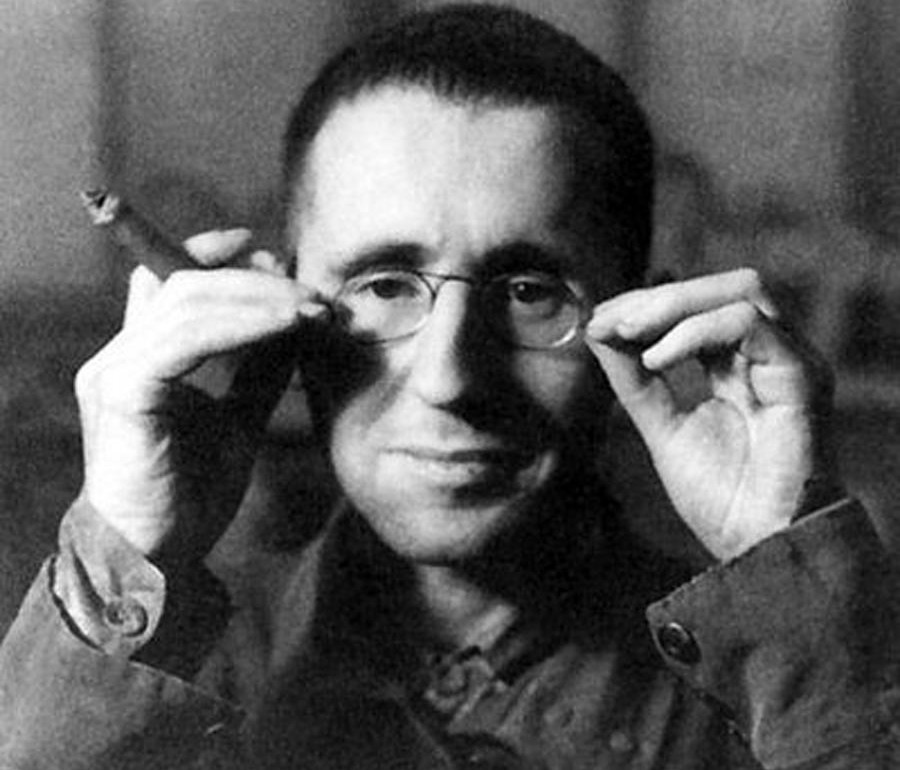

In his own statement, Mr. Kulick writes that he wanted to answer the question, “Can you treat a Brecht play like we now treat a Shakespeare play?” For a very long time now, theatre artists have treated the works of Shakespeare as blank checks. No writer has anywhere close to the name recognition or box-office pull that Shakespeare has. And so, taking advantage of the obscurity of the language to a modern audience, not to mention the fact that the plays are in the public domain, theatremakers have used Shakespeare’s work to essentially write new plays, to tell stories they worry they couldn’t get audiences to see without that famous name on them.

But Shakespeare didn’t write plays about the Democratic Republic of the Congo or about World War II or about gang warfare in U.S. cities. I would argue that he didn’t even really write plays about Denmark, Venice, Ancient Greece, or even British history. He wrote plays about life in England at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century that were set in some of those other places and times. Likewise, though Brecht was writing about World War II, he set Mother Courage in the 17th century, during the Thirty Years War. Surely these plays have universal themes, but that does not automatically make them universal. When we transpose these plays we risk muting the specificity that makes them vibrant.

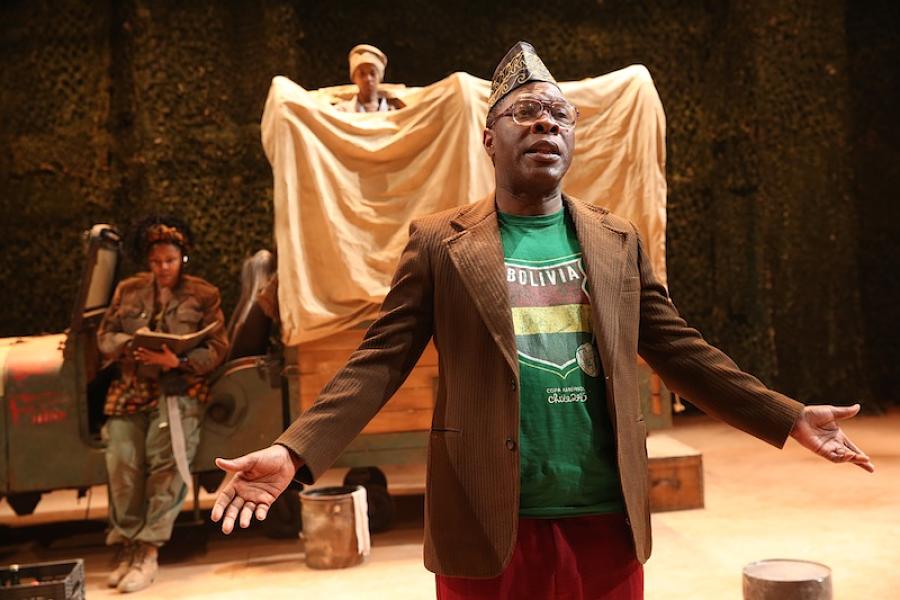

What’s more, even when transposed, these plays can never really capture their new settings with any specificity either. That vagueness is perhaps most damaging when, as in this case, it comes in the service of diversity. Sometimes that damage comes in the form of stereotype and appropriation, as in the case of a 2011 Washington, D.C., production of Much Ado About Nothing which was set in Cuba but featured only three Latino actors and changed the characters of Hugh Oatcake and George Seacoal to Juan Huevos and Jose Frijoles. Other times, as seems to be the case with CSC’s Mother Courage, the problem is one of missed potential. It is clear from Pinkins’s statement that she leapt at the opportunity to play Mother Courage not only because of the artistic opportunity it offered her but because she believed that black women deserved a strong character like Mother Courage to represent them onstage. Pinkins’s vision of a strong black Mother Courage ran up against Kulick’s contrasting interpretation of a character Brecht never wrote as black in the first place.

In another situation, a director and actor may differ, and only artistic egos are at stake. But with the promise of a rare strong black female protagonist on the line, we can understand Pinkins’s disappointment. Mother Courage was never going to be about war in the Congo, because it was written by a playwright who died more than 40 years before the First Congo War began. Pinkins credits Lynn Nottage’s Ruined as the inspiration for the setting of CSC’s Mother Courage, but Nottage has said that she eventually realized that just doing a strict adaptation of Mother Courage wouldn’t do justice to the story she was trying to tell. Great plays have specificity that is not easily traded in for a new setting. Ultimately, casting a black Mother Courage may give an actor like Tonya Pinkins an all-too-rare meaty role, but a play by Bertolt Brecht will always be hard-pressed to bring a black perspective.

If CSC wants to do classic plays with black perspectives, perhaps they shouldn’t look to Shakespeare or Brecht but to Lynn Nottage, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Suzan-Lori Parks, or Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, to name four playwrights off the top of my head who have all taken on classical material in recent memory. (I mean, if you want to do a play like Mother Courage and set it in the Congo, I can’t really fathom why you wouldn’t just do Ruined, unless you had a really fantastic version by a Congolese playwright.) Or why not add some classic plays by black writers? Surely if Pinter’s The Birthday Party (produced at CSC in 1988 and again in 1989) is a classic, so are such mid-20th-century plays as Adrienne Kennedy’s Funnyhouse of a Negro, Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, and James Baldwin’s Blues for Mr. Charlie.

Through this lens, though, the problem becomes uncomfortably clear. With the caveat that race is hard to conclusively ascertain by Google search, from a perusal of the season archive page on CSC’s website, it looks to me as though, since the company’s first season in 1968, only about five writers of color have had their work onstage there in some form or another. That tally includes a play by Alexandre Dumas, whose grandmother was an African slave, in translation by Michael Feingold, who is white, as well as Salman Rushdie’s novel Haroun and the Sea of Stories, adapted by an unlisted writer as part of shared bill called “Books on Stage.” As far as I can tell, of those five or so writers of color, only Migdalia Cruz, with Another Part of the House, her 1997 take on Lorca’s La Casa de Bernarda Alba, has had her own words spoken onstage at CSC in the original language.

The same archive only lists directors as far back as 2003, but in that time, with the same caveat as above, only a few directors of color have worked at CSC, almost all of them in collaboration with white directors or on shared programs. If Tonya Pinkins wants to play Mother Courage, she should find, and I hope she finds, a director who shares her vision. But if CSC really wants to put black perspectives onstage, which they should, they might consider staging a play not written by a white playwright and directed by a white director.

The eight playwrights mentioned above, of course, represent just a tiny fraction of the potential for bringing African-American perspectives to CSC’s exploration of the classics, not to mention other perspectives available in a city as diverse as New York. And why not bring a more global perspective by tackling non-Western classics like The Orphan of Zhao, Atsumori, or The Little Clay Cart? Brecht and Shakespeare were both great writers, but it’s time we stopped expecting them to speak for everyone.

McFeely Sam Goodman is a playwright and a middle school English teacher. He is in his last year of an MFA at Columbia University.