Hoots and hollers fill the room as Dominique Morisseau enters New York City’s Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater for the 2015 Steinberg Playwright Awards. She waves and blushes slightly as she walks down the aisle to her front-row seat and her friends call after her. She doesn’t always get this much attention, but tonight she’s accepting one of two $50,000 annual awards the Steinberg Charitable Trust awards to playwrights (the other honoree is Branden Jacobs-Jenkins).

Kamilah Forbes introduces her; the two go back 15 years, when Morisseau submitted one of her first plays to the Hip-Hop Theater Festival, of which Forbes is producing artistic director. In 2013, Forbes directed the U.S. premiere of Morisseau’s Sunset Baby at Labyrinth Theater Company. In her affectionate speech for her friend and colleague, Forbes listed three things that come to mind when she thinks of Morisseau: viral videos, Facebook posts, and silver hoop earrings.

The first is a reference to Morisseau’s famous wedding video, which garnered half a million hits on YouTube since its posting in the summer of 2013. It shows her and her husband, hip-hop artist Jimmy Keys, blowing up the reception dance floor to a medley of tunes. The second is a callout to Morisseau’s vibrant presence on social media, where she writes extensive, poetic posts on the state of race relations, gender equity, civil liberties, and more.

And the third? Well, she’s always wearing her hoops.

She’s sporting them when I meet her at the Lark Play Development Center the next day. (“These aren’t as big as I’d like them to be,” she says with a laugh, demonstrating that while she can get one wrist through the hoop, she’d prefer earrings big enough for both arms.) As we walk into the building, she greets everyone with a hug and a smile, from the security guard to the receptionist. Everyone knows her name, and each greeting is accompanied by a long-held embrace, as she’s just returned to the city after spending seven months in L.A. on the writing staff of the Showtime series “Shameless.” “Gimme some love!” Morisseau says to one and all.

The Lark is one of the places she got her start, acting in Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop and later receiving a yearlong Playwright of New York (PoNY) fellowship. Now her work is everywhere: She is on American Theatre’s list of the 20 most-produced playwrights for the 2015–16 season, with 10 productions of her work happening across the country. The final installment in her Detroit trilogy, Skeleton Crew, premieres at the Atlantic Theater Company in New York City (Jan. 6–Feb. 14).

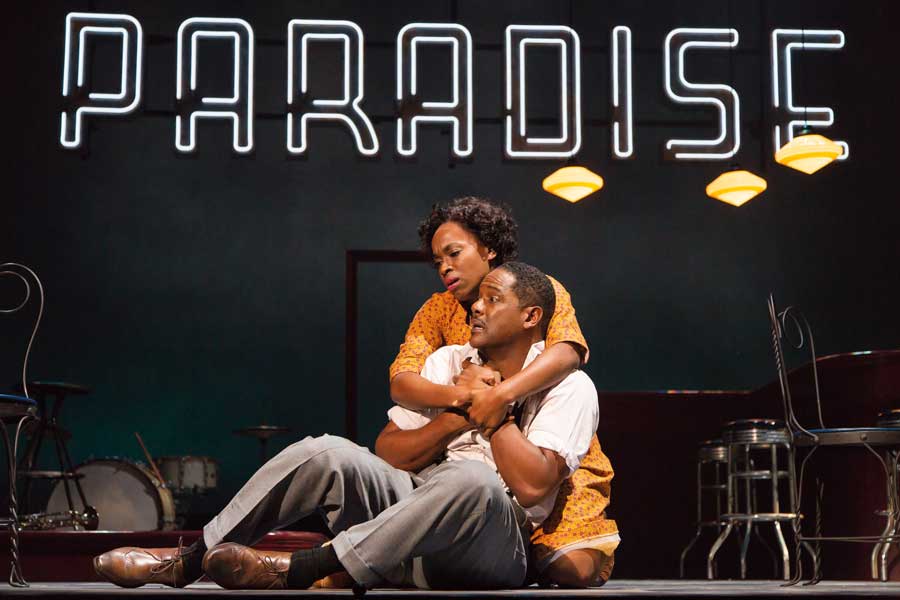

This play cycle spotlights three moments in the history of the city where Morisseau was raised. Detroit ’67, which premiered in 2013 in a three-way coproduction between the Public Theater, the National Black Theater, and the Classical Theater of Harlem, is set during the city’s bruising 1967 riots. Paradise Blue is a jazz-filled exploration of Paradise Valley, where music icons like Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald performed in the late ’40s before the neighborhood was shut down due to so-called urban renewal projects. And finally, Skeleton Crew is set in 2008 at a small stamping plant amid the downturn of the auto industry.

“Dominique is a healer,” says Ruben Santiago-Hudson, who directed Paradise Blue at the Williamstown Theatre Festival over the summer and will helm Skeleton Crew. “There’s a disease in African-American communities—it’s a metaphor in a sense, but it’s a reality that I face—and the disease is ignorance. We rarely get to see African-American people at the center of the world, the salt-of-the-earth, wonderful, angry, joyous, loving, beautiful people. Dominique takes the marginalized people—not just marginalized in America, marginalized even in the African-American community—and gives them a story, gives them a voice. So she heals that disease.”

Santiago-Hudson lived in Detroit for five years while in graduate school, and says he was attracted to Morisseau’s work because it put Detroit “in a human light.” For her part, Morisseau was inspired to dramatize Detroiters after reading the works of Pearl Cleage—a Detroit-raised playwright, essayist, novelist, and poet—and the plays of August Wilson.

What she loves about Wilson’s work, she says, is “the way he captures the jazz, and the way his people spoke in Pittsburgh. I thought how affirmed they must be when they read his work; they must feel so visible. I wanted to do that for Detroit, mostly because I felt that the narrative I know about the city is not visible. And I want to address the stuff that has been a conflict for us in the way that August Wilson did, and be a griot, a storyteller for them.”

Though she was raised in Detroit, her mother’s family is from Mississippi, and her father’s family is from Haiti, so Southern and Caribbean language fill her vocabulary. She heard phrases like “gotta get some vittles in that tummy” from her grandmother, or, one she put into Skeleton Crew, “If you’re feeling froggy, go on and leap,” which she stole from her husband, whose family also comes from Mississippi. As Forbes notes in her Steinberg speech, the characters in Morisseau’s plays possess “pieces and shreds and glimpses of people who have raised Dominique, who she loves and cares for fiercely.”

“We speak in poetry,” Morisseau says of her family and her husband’s family. “They’re not trying to be poets; it’s just something a little more obscure and specific about how they’re talking. It’s very colorful language. I’ve never thought about why it is; it’s just how I hear it.”

Her family was also crucial to her research for the Detroit trilogy, as she wrote the plays largely to learn more about her city and in the process learned more about her relatives, as well. She had no idea, for instance, that her uncle was a journalist during the 1967 riots. He essentially became her “teacher” while she wrote Detroit ’67.

“I pretty much jacked their memories,” she says. “It has a lot of my own family history spilled throughout the play.”

Still, she’s shocked how often people ask her if she wrote the play in response to such current events as the deaths by law enforcement of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and others.

“I’m like, ‘Did I write a play called Detroit ’67 because of what’s happening now? No, I wrote it because of what was happening in 1967!’” says Morisseau. “I had no idea that it was about to be mirroring what’s happening now. I’m just wondering, how many more plays are we going to have to write before that is a past and not a present?”

Kwame Kwei-Armah directed Detroit ’67 in New York, and this season the play will appear at Center Stage in Baltimore, where he’s artistic director, with Forbes at the helm. He had initially slated a different play, but after the death of Freddie Gray in police custody and subsequent protests in Baltimore, he reached for Morisseau’s play. While the play visits a painful and unfortunately recurring chapter of black history, Kwei-Armah feels that the playwright goes further than simply portraying her culture’s internal conflicts.

“It’s really easy to celebrate our dysfunction as a community, and the majority

theatregoer—our white brethren and sistren—sometimes fascinate at our own destruction,” Kwei-Armah concedes. “Dominique tends to be very much aware of that. So she’s writing not to perpetuate the stereotype, but she’s writing out of a truth in order to ask a political question of the community that she comes from: How can we do better?”

Morisseau is certainly aware of the media-perpetuated stereotypes surrounding her hometown, which is one reason she wanted to reclaim its stories on her own terms. She recalls the time a teacher at University of Michigan, where she studied acting with her now-husband, asked students to call out words to describe Detroit. One adjective, “degenerate,” made Morisseau and Keys weep in each other’s arms.

“I definitely think people come in with assumptions about Detroit,” Morisseau says of her play’s audiences. “Detroiters know that people feel negatively about the city, so they’re very particular about who’s going to write us. When I tell people from Detroit that I’m writing about the city, the first thing they say is, ‘Okay, make us look good now.’ And I’m like, ‘Why? That’s not an interesting play!’ I’m not going to do that. But what I promise is: I’m not going to make you look bad. I’m going to make you look human. Because that’s what we are.”

at Labyrinth Theater Company. (Photo by Monique Carboni)

That humanity extends beyond the Motor City. Morisseau recently went to Russia with the Lark for a Translation Project with her play Skeleton Crew. While Russian artists strongly identified with her story of oppressed workers struggling to find meaning, the process of translation and production was “mind-blowing” and “rough.”

“There’s not a lot of black actors over there,” says Morisseau. “I ended up having an all-white Russian cast for my play about black people in Detroit.” While she admits that the experience was “upsetting—it became profound for me,” the issue of language was also fraught, as many terms in Morisseau’s plays are culturally specific. “I battled with them a lot about translating and not saying certain words and phrases in my play that were no longer applicable—especially words that were very specific to black American culture that would be offensive if said outside of that community.”

Morisseau says she hates the adjective “universal” (“Aren’t all stories universal?”), but there is undeniably something about her work that transcends the immediate situations of her characters. Kwei-Armah recalls a moment from an early workshop for Detroit ’67 when he compared her play to Chekhov, and the team got defensive for a moment.

“Someone said to me, ‘Yeah, but it’s black, right? You’re not saying it’s not black?’” remembers Kwei-Armah, who is black British. “The way this sister loves her brother too much, and his negotiation with the frustration of being loved and over-protected, is totally Chekhovian, but coming from a British voice, it sounded like I was trying to deny something.” That’s not what he meant, of course, but he chalks up the moment to “her precision when it comes to representing her city.”

Morisseau also comes at her work from an actor’s perspective; acting was her first love, and she continues to pursue acting roles. While she hasn’t been in any of her plays yet—and says she would never act in a premiere of her work—there is a list of characters she’d like to play (some of them are the men in her plays).

And whether she covets them or not, she does set out to write roles actors will want to play. In her Steinberg acceptance speech, she thanks “the actors who develop my work and then don’t get the opportunity to be in its world premiere.”

It’s an experience she knows all too well: She worked for years on Hall’s The Mountaintop. Indeed, Hall essentially wrote the role of the hotel maid who has an imagined encounter with Martin Luther King Jr. for Morisseau, who performed it throughout all the initial workshops. But when the play became a commercial property, star actors were cast in London and then Broadway (Lorraine Burroughs and Angela Bassett, respectively). A golden opportunity had seemed to slip away.

“It just felt like mine,” Morisseau says of the role of Camae, but out of the heartbreak she learned “that nothing really belongs to any of us. It sounds tragic, but not really. It really taught me that our job as actors is to tell the story, and especially with new writers, it’s to help them develop their work and touch it and make it better. If the work is intended for us, it will come back to us.” (And it did: Morisseau performed the role at Kentucky’s Actors Theatre of Louisville in 2013.)

The acting impulse is what drove her to playwriting. She wrote her first play because of the lack of roles for her in college, where she felt marginalized as one of three black women in a program that didn’t produce works of color or support nontraditional casting at the time. So she wrote The Blackness Blues: Time to Change the Tune, A Sister’s Story (she also directed, choreographed, performed in, produced, and designed lights for it). The response was overwhelming.

“I remember students were rushing to try to get in, and one of my classmates said to me, ‘Hey Dominique, hook me up!’” she recalls. “I was thinking, Hook me up? That’s what we say when we’re trying to get into the hot party. And I was like, ‘Oh my God, my play is the hot party!’ I’m sold; I’m doing this for life.”

She still has that inner fire. For many years, she worked as a teaching artist with City University of New York’s Creative Arts Team. At the Steinberg Awards, Morisseau recalls a time when her City University mentor and boss, Gwendolen Hardwick, wanted to speak with Morisseau’s Michigan professor Glenda Dickerson about her. Morisseau says she was nervous; she worried that Dickerson might not remember her fondly from school, because she was “angry” then. “Sometimes a little anger is necessary,” Hardwick told her.

“I can’t tell you the magnitude of those words for me,” Morisseau says from the podium at the Newhouse, to loud shouts of affirmation from the crowd. “I am an artist. I am a writer. Until those words, I had carried a shame for my anger—an anger that, though warranted and justified, was a burden to which I felt misunderstood and socially unaccepted. Never mind the provocation of my anger—that never seemed to matter. The anger alone was my sin.

“Now as a playwright, that anger is my liberation. It is my passion for justice. It is power. It is characters who I love deeply. It is beauty, imagination, activism. It is theatre.”

And the crowd says amen.